There’s a pretty good argument to be made that a lot of the differences between people’s opinions on controversial issues have more to do with differences in temperament and its influence on world view than with the facts or arguments related to specific conflicts. Journalist Chris Mooney has made a compelling case, based on extensive research in psychology, that our political opinions, for example, are shaped more by our temperament than our experiences. And that temperament is determined largely (perhaps 70%) by our genes.

Such a theory certainly seems to explain some of the ideological divisions in the U.S. today, and the intense and reason-proof arguments often seen around so-called “culture war” issues. It would also explain why facts and rational arguments are of so little value in challenging faith-based beliefs, both those pertaining to alternative medicine and those in other domains. Ultimately, a clash of philosophies, built largely on a clash of personalities, may underlie arguments that seem like differences of opinion about factual matters but which seem insoluble and intransigent no matter how much data is available.

Of course, this is a simple theory about a complex subject, human belief and behavior, and it may very well not be correct. Certainly, it can’t be said to be established beyond any reasonable doubt. Still, I find it intriguing and perhaps enlightening.

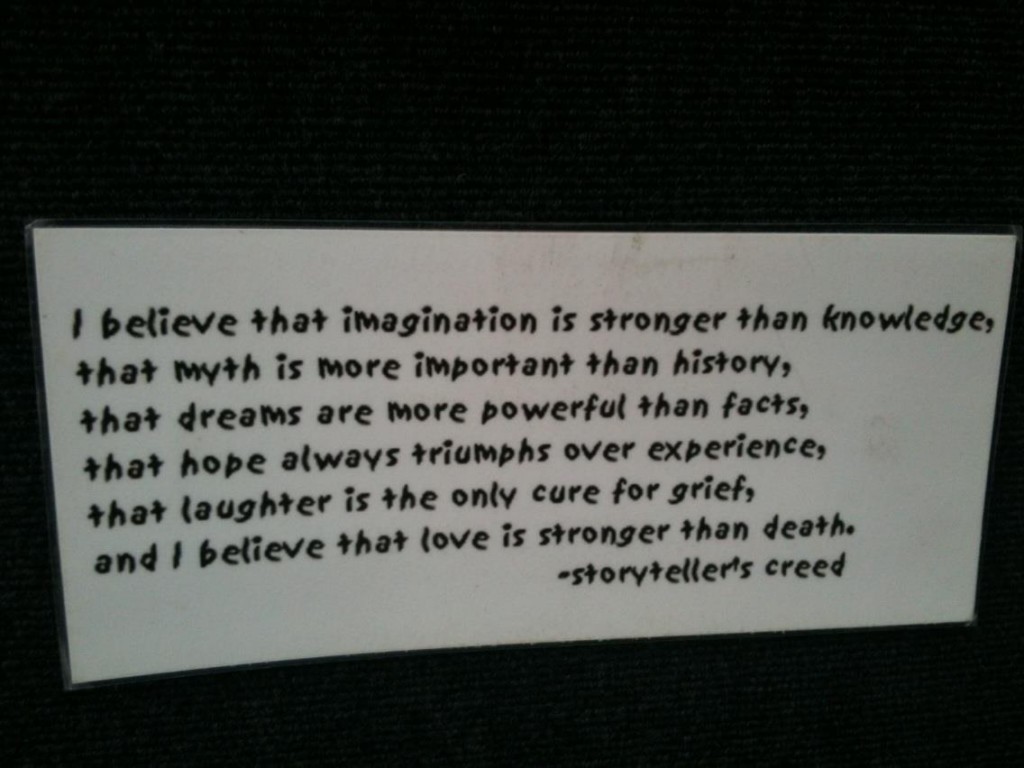

I ran across the credo below at an art fair last week. My own reaction to it was that it represented the kind of thinking that is behind many of the worst choices and arguments people make. Willful denial of reality in favor of what we wish were true can’t be a sound basis for decisions, in medicine, politics, or any other area involve the world outside our own minds.

I would never deny the importance and power of imagination, hope, love, or other core human feelings. Anyone who knows me will attest I am nothing if not intense in my feelings. Still, I find this set of statements naïve at best and perhaps even a little offensive. Obviously, others see it in a much more positive light. I suspect, though I can’t see any way to prove, that how one reacts to this credo might very well be predictive, to some extent, of how one views religion, alternative medicine, and other areas of conflict between reason and emotion, skepticism and faith.

I’d be interested in any thoughts or reactions to the series of principles that inspired it.

I don’t see how the storyteller’s creed can be viewed as anything but ridiculous. But I guess I just lack the imagination that is claimed to triumph over knowledge.

I suspect telling a story to a dog will not produce better outcomes. I “believe”that when I tell a story to a client rather than present the data the clinical outcomes are not as good. Story telling is like wearing a tie and white coat. Anyone can tell a story put on a tie and coat and get paid. Presenting the evidence to clients for what we do takes a lot of training and effort. I have read storytelling in the doctors office has been increasing the last few decades. There are prospective randomized studies showing storytelling produces better health outcomes. How much of that is the placebo effect with side effects I am not sure.

Art malernee dvm

That is a statement of fantasy written by someone who is ‘away with the fairies, not to be taken at all seriously

had this not been found at an art fair, I would suspect it as being nothing less than a wickedly fine piece of satire.

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/10/healing-through-storytelling/

I am a professional storyteller and I find that creed to be generally offensive. It would be better labeled “the Woo Peddlers’ creed”. Don’t let this bit of nonsense tarnish your view of storytelling any more than you’d allow a climate change denialist masquerading as a “scientist” to influence your opinion of all scientists.

Just as the hellfire-breathing fundamentalist, extremist, young earth creationist shouldn’t speak for all people who claim some degree of spirituality, this “creed” does not even come close to representing the views of the vast majority of storytellers I know.

I would like to think most storytellers do a better job of representing our profession in the world. A good storyteller can instill a reverence for history, knowledge, experience and facts.

-Ira McIntosh, Andes, NY

No worries, I’m a huge fan of storytelling in all its forms. In fact, part of what is challenging about promoting a scientific understanding of the world is that narratives are far more psychologically compelling that data, and we are hard-wired to learn best through stories. The trick is to use that in teaching the truth and be aware of the danger of getting caught by a narrative that is compelling but disconnected from reality (in the area of science, of course. I don’t expect deliberate fiction to obey any such rules, naturally).

Thanks!

It would be difficult to reconcile these comparisons. The author is comparing things that are of different semantic types and are therefore not comparable. They are no more sensible than comparing the flavors of a strawberry to grains of wood. What is interesting is they are mostly comparisons of things that are immutable (experience, history, death) to those that are mercurial (dreams, hope, imagination). Or in other words, things they have some control over.

This suggests the storyteller seeks optimism. Through stories, the author builds a tribe of readers that gives validation and comfort. For a clinician, the same motive of optimism may exist in “stories” about unfounded claims because it helps by freeing themselves from the normal but frustrating uncertainties intrinsic to medicine and in turn brings that sense of hope to their clients. It’s also easier than the more exhaustive effort required to critically appraise what evidence exists. To give the benefit of doubt, we’ll say this is because people are too busy, not lazy. But perhaps their just lazy.

At the risk of extending your storytelling exemplar too far, I’m also interested in the nature of heroism in medicine. Do clinicians view themselves as the protagonists in a story of disease? Do they consider themselves generally normal, but uniquely skilled, when facing exceptional situations? Does a homeopathic practitioner consider themselves an antihero against allopathy and who further seeks camaraderie and validation through their tribe (the CAVM community)?

What is common among stories or myths and medical pseudoscience is the effort to explain things at such high levels of abstraction and imagination. It’s almost at the level that we explain things to young children in fear the details will either not be understood or too close to reality. This is why I find the lack of detail, inquiry and effort to review the evidence by clinicians BEFORE presenting cases to their colleagues (e.g. Q: “I heard about this herb, what do you y’all think?” A: “What specifically do you want to know?”) insulting and embarrassing.

Much like a storyteller weaves imaginative concepts, a practitioner can weave phenomenal abstract notions of energies and magical intentions or the notion that an earlobe is a dynamic, reactive and fully representative model of the whole body such you can stick something in a precise area and yield a cure.

Excellent and thoughtful response, thank you. I think, with only weak evidence, that we are hard wired to learn and teach via narratives and to build internal narratives to give coherence and a sense of comprehensibility to our lives, which reduces our fear.