I have written extensively about the scientific evidence concerning the benefits and risks of neutering. Overall, the data is complex, and significant effects of neutering on specific health risks are rarely definitively demonstrated. One of the most controversial issues, the influence of neutering on cancer risk, illustrates this. Some cancers are more common in neutered animals, some are more common in intact animals, and the effect of neutering on cancer risk varies with sex, breed, age at neutering, and possibly other factors. When looking at the issue in cats, we have the added challenge of far less research data than is available for dogs. However, one new study has added a bit more information to help evaluate the subject.

Graf R, et al. Swiss Feline Cancer Registry 1965-2008: the Influence of Sex, Breed and Age on Tumour Types and Tumour Locations, Journal of Comparative Pathology (2016).

There are a number of limitations to this paper that have to be considered. Laboratories in Switzerland that analyze tumors contributed data to a central registry. The study reports an analysis of data collected in this registry over a very long period of time. This often creates problems since definitions of disease and the behavior of animal owners and veterinarians, in terms of relevant issues like how likely to diagnose and treat cancer, submit samples to laboratories, and so on, change over time. The data collected at the beginning of the time period analyzed may or may not be truly comparable to the data collected later.

Also, use of the registry is voluntary, so it is not clear how representative this data is of the overall cat population in Switzerland, much less anywhere else. And exactly how the data is collected and processed is not reported in the paper, and many important terms are not well defined. For example, it is not clear how cats are classified as neutered or intact, and there is no discussion of the age at which neutered cats are neutered, which has been an important factor in other studies. So evaluating potential sources of bias and error effectively is impossible, and therefore this is the sort of data that have to be taken with some skepticism.

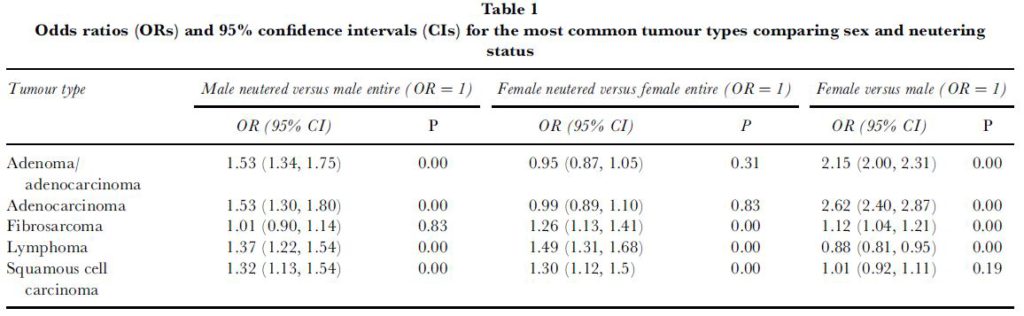

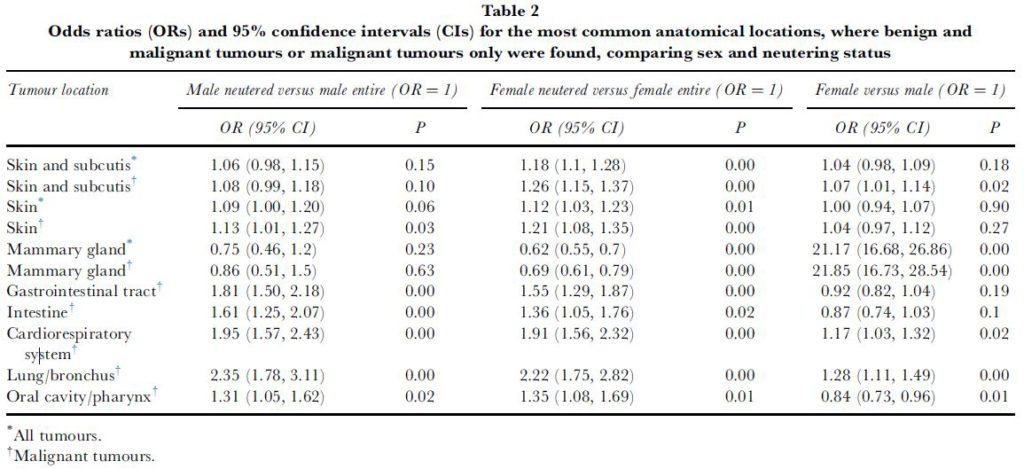

Nevertheless, given the paucity of data on the effect of neutering on feline cancer risk, this paper is a useful addition. The portion of the report that relates to neuter status is contained in the following two tables:

There are several interesting patterns that can be discerned in these tables. The first is that there is a pretty consistently higher cancer risk in neutered cats compared with intact cats. This ranges from about 25-50% higher for most cancer types, though there are some for which there is no apparent difference in risk (fibrosarcomas for males and adenomas/adenocarcinomas for females).

Looking at specific tumor locations, the general pattern is for neutered cats to have a higher risk of tumors in some locations (skin, gastrointestinal tract, cardiorespiratory system, and oral cavity) and a lower risk for mammary tumors (in both males and females, though females are at much higher risk overall for mammary tumors than males, whether intact or neutered). If these differences are consistent in other study populations, it might help shed more light on the specific mechanisms by which sex hormones could be protective against some cancers while neutral or even a risk factor with respect to others.

While there are many limitations and caveats to these data, they do suggest a pretty consistent mild-moderate increase in cancer risk associated with neutering in cats. As always, this has to be balanced against the other health risks and benefits associated with neutering, as well as other important issues, such as the ethical and environmental impact of cat reproduction. This paper emphasizes the complexity of biology and the multifaceted potential effects, both good and bad, of any intervention which significantly effects the physiology of our animal companions and patients.

Very interesting, thank you for this. Looking at the much higher risk of lung and other respiratory cancers amongst neutered cats one does wonder what the smoking rates were amongst their owners. Neutered cats are far more likely to be indoor pets than those that remain entire…

Frances, some tumors are highly aggressive, meaning metastasis to lungs (or heart, other organs) could be a common but unfortunate prediction for a specific tumor. Not sure this study is saying these are primary tumor sites at diagnosis without metastasis, just saying it’s a possibility. I guess it’s possible to say lung/respiratory possibly caused by second-hand smoke from the owners, but the likelihood may be much smaller.

I have always referred to spaying a female dog or cat, and neutering a male dog or cat. Are you using the term neutering to both male and female cats?

Yes, the term “neutering” technically means removing the gonads, which applies to either males or females. By traditional, we usually use “spay” for females. “Castration” is more often used for males, but can be used for females as well.

This is very helpful. I have a 5 year old intact male (Sphynx). You wouldn’t believe the amount of rude comments I receive from breeders (and other folks) implying that I’m irresponsible because I won’t neuter him. Of course they try to convince me there is irrefutable evidence that he is at high risk of getting cancer. I have yet to read or see any compelling evidence that proves this is the case. thanks for this article!

I had read the stats on mammary and uterine/ovarian cancers in cats if spayed after a year old, If they are spayed later in life I guess that would take care of the uterine/ovarian cancers but not the mammary.

I was wondering if having a litter of kittens before being spayed at about 1 year – 1.5 years of age be of any significance? If a cat had a litter at say 9 months old but was spayed afterward, is there any increase in cancer risk?

I assume they would likely have a higher potential for mammary cancer at a year and a half based on the age but I wasn’t sure how having a litter of kittens would impact their overall health span and longevity.

Most of my cats have lived to about 20 years of age but one had a cancer in her neck and chest and died at about 12-15 years old but she never had a litter and was spayed before a year old, however losing both cats in the last 2 years (one of cancer and the other of old age) I am looking to avoid going through that again any time soon… the senior cat only had declining health (went deaf and developed cataracts and arthritis and a heart murmur) in the last 2-3 years of her life.

I am looking at adopting a couple cats soon but a good number of them had litters or were spayed/neutered after a year old so I am looking to try and reduce the risks.

Thanks

Joe,

Skeptvet could more than likely provide statistics if available, but would only add, to take into account a female cat’s number of heat cycles prior to spaying. I would think if the female had one litter, and was spayed before 1 year of age, or 1.5 yrs of age, the possibility of mammary/uterine cancers are of course, significantly reduced by spaying early on (and that awful, serious, life-threatening condition known as pyometra, spaying early and not allowing mating/kittens is ideal – not to mention the pet overpopulation).

I would also like to add, don’t avoid adoption simply because an available cat has had a prior litter or was spayed as a very young adult. All pets are deserving of a good loving home 🙂