INTRODUCTION

Experienced clinicians often have an enormous knowledge base about the health problems their patients present with and the available diagnostic and therapeutic options. This knowledge is built over time from a variety of sources: basic pathophysiology and clinical information learned in school; practice tips and pearls imparted by professors and speakers at continuing education meetings; review articles and primary research papers in veterinary journals; textbooks; advice from mentors and colleagues in practice; and, of course, clinical experience with previous cases.

This knowledge base smoothly and efficiently informs the day-to-day activities of clinical practice. When cases with familiar features are seen, the appropriate diagnostic and treatment steps often come to mind automatically, or with minimal prodding. Unlike students and new graduates, experienced clinicians often have little sense of dredging up facts committed to memory and more of a sense of simply knowing things. One of the hallmarks of expertise is that the collating of observations and relevant knowledge into a coherent picture of the problem and a plan become less deliberate and more automatic with time.1

While this process, which is a universal and automatic feature of how the human brain functions, leads to greater efficiency than the explicit, conscious use of algorithms and reference sources employed by less experienced practitioners, it has some serious limitations. One problem, for example, is that the knowledge one relies on often can no longer be connected to its original source. We often simply know things without being aware of how we came to know them. This limits our ability to judge the reliability of the source of our knowledge. In fact, such established, automatic knowing often generates a sense of certainty greater than that which accompanies deliberately seeking and finding information.2 We are more likely to trust what we already know, even if we don’t remember where we learned it, than we are to trust what we have just discovered after searching a trustworthy source of information.

There are also a large number of well-characterized cognitive biases and sources of errors inherent in how our brains acquire, process, store, and utilize information that can lead us astray.3 These are more likely to create error when our reasoning is automatic rather than deliberate, as it necessarily must be in an efficient clinical environment that is not devoted primarily to teaching.

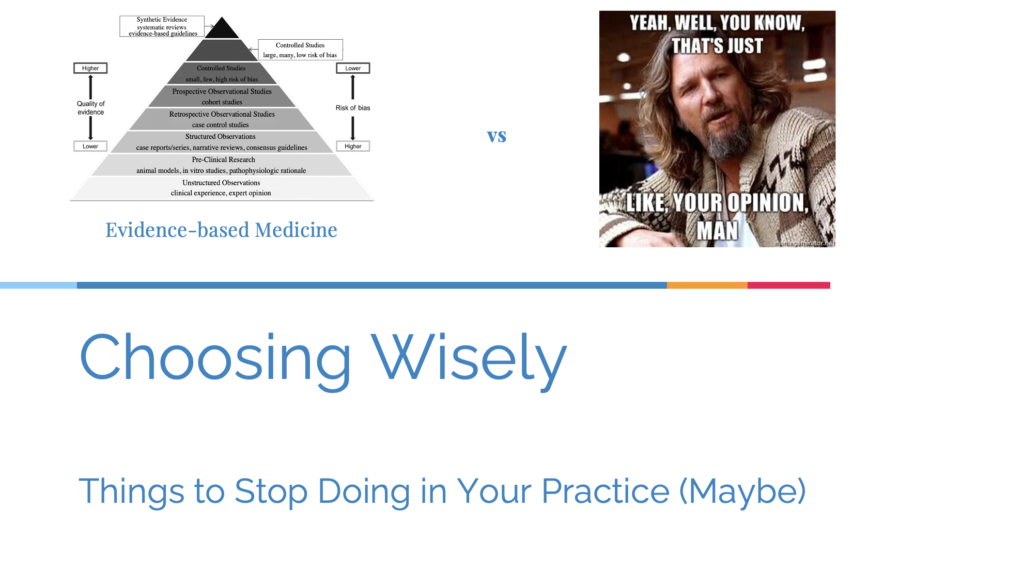

One of the major functions of evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) is to provide tools and resources to make the knowledge base we employ more reliable. This includes generating better quality information through research and facilitating the integration of that information into clinical decision making. When the relevant evidence is of high quality, this can add confidence to our decisions.

More commonly, when the evidence has significant limitations, we may end up with less confidence in our knowledge than we would have without an explicit evaluation of the evidence. However, this is not as undesirable an outcome as it may appear. A clear, accurate understanding of the uncertainty associated with a particular practice protects us, and our patients, from the dangers of acting with unjustified confidence. We are more likely to weigh thoughtfully the risks and benefits of action in the context of an individual case when we understand the degree of uncertainty about our ability to predict or manipulate the patient’s condition.

Being clear about the sources of our knowledge, and the appropriate level of confidence to have in them, also aids in fulfilling our duty to provide clients with informed consent. Surveys of veterinary clients have shown that they value truthfulness highly in the information we provide to them, and that they want to be made aware of the uncertainties involved in the treatment of their animals.4-5 Only if we understand the reliability and limitations of the information we employ in making our recommendations can we give clients the knowledge and guidance they need to make informed choices.

The purpose of these lectures is to examine some widespread or long-standing beliefs and practices in small animal medicine and assess their evidentiary foundations. In some cases, this may clearly validate or invalidate these beliefs. In most cases, however, such an exploration will likely not lead to greater certainty but to a clearer understanding of the degree of uncertainty associated with these beliefs. Hopefully, this will be useful in making clinical decisions and in communicating with clients. The exercise may also be useful in illustrating how to make use of the research literature in establishing and maintaining the knowledge base that informs one’s clinical practice.

Some of the topics that will be covered include:

- Metronidazole as a treatment for diarrhea

- Tramadol as an oral analgesic

- Vitamin C and steroids in sepsis

- Common use of gastroprotectants

REFERENCES

- Benner, P. From novice to expert. Amer J Nursing, 1982; 82(3):402-7.

- Burton, R. On Being Certain: Believing You’re Right Even When You’re Not. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 2008

- McKenzie, BA. Veterinary clinical decision-making: cognitive biases, external constraints, and strategies for improvement. J Amer Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(3):271-276.

- Mellanby RJ, Crisp J, De Palma G, et al. Perceptions of veterinarians

and clients to expressions of clinical uncertainty. J Small

Anim Pract 2007;48:26–31.

- Stoewen DL, et al. (2014) Qualitative study of the information expectations of clients accessing oncology care at a tertiary referral center for dogs with life-limiting cancer. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245(7):773-83.

Please tell us your thoughts on the claim that grapes are poisionous.

It is well-established that some grapes can lead to severe kidney damage in some dogs, but their causal agent and other important information about how this happens has been elusive. A recent study provides a pretty solid hypothesis that tartaric acid is the toxic element involved, and if that is confirmed then I think the case will be pretty compelling.