I recently gave a lecture at the Western Veterinary Conference called “What You Know that Ain’t Necessarily So.” The purpose of this was to take some common or controversial beliefs and practices in veterinary medicine and discuss the scientific evidence pertaining to these. This was not intended as a definitive, “final word” on these subjects, but as an illustration of how weak and problematic the evidence often is even behind widely held beliefs. In some cases, these practices or ideas may actually be valid, but without good quality scientific evidence, we should always be cautious and skeptical about them.

Eventually, I will post recordings of the presentations themselves, but for now I am posting a summary of each topic.

Each starts with a focused clinical question using the PICO format.

P– Patient, Problem Define clearly the patient in terms of signalment, health status, and other factors relevant to the treatment, diagnostic test, or other intervention you are considering. Also clearly and narrowly define the problem and any relevant comorbidities. This is a routine part of good clinical practice and so does not represent “extra work” when employed as part of the EBVM process.

I– Intervention Be specific about what you are considering doing, what test, drug, procedure, or other intervention you need information about.

C– Comparator What might you do instead of the intervention you are considering? Nothing is done in isolation, and the value of most of our interventions can only be measured relative to the alternatives. Always remember that educating the client, rather than selling a product or procedure, should often be considered as an alternative to any intervention you are contemplating.

O– Outcome What is the goal of doing something? What, in particular, does the client wish to accomplish. Being clear and explicit, with yourself and the client, about what you are trying to achieve (cure, extended life, improved performance, decreased discomfort, etc.) is essentially in evidence-based practice.

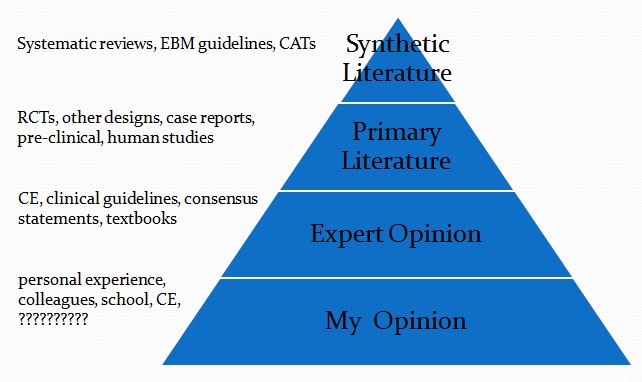

This is then followed by a summary of the evidence available at each of the levels in the following pyramid (which is a pragmatic reinterpretation of the classical pyramid of evidence that is a bit more useful for general practice veterinarians).

Finally, I list the Bottom Line, which is my interpretation of the evidence.

Pre-anesthetic Bloodwork in Healthy Animals

- Clinical question

P– healthy dogs & cats

I– routine cbc/chem before anesthesia

C– no bloodwork

O– mortality, complications, change plan

2. Synthetic Veterinary Literature

a. Systematic Reviews- none

b. CATs- none

c. Guidelines- none

3. Primary Veterinary Literature-

- cbc/biochemistry profiles for 1537 dogs

- university surgery population

- variety of ASA stages

- No indication in PE/Hx for labwork in 84%

- Recategorized in ASA level- 8%

- Procedure postponed- 0.8%

- Additional therapy- 1.5%

- Change in protocol- 0.2%

- Complications in 1.9% of patients

- Lab values normal or unrelated in 84% of these

- 3.8% incidence with lab abnormalities

- 1.8% incidence with normal labs (no statistical difference)

The changes revealed by pre-operative screening were usually of little clinical relevance and did not prompt major changes to the anaesthetic technique…In dogs, pre-anaesthetic laboratory examination is unlikely to yield additional important information if no potential problems are identified in the history and on physical examination.

(Alef, 2008)

- 101 dogs

- Private practice

- > 7 years of age (avg=11)

- Routine and emergent cases

- 87% had no pre-existing conditions

- New problem found- 29.7%

- Anesthesia cancelled- 12.9%

- Further tests- 5.9%

- Euthanized- 4%

- Procedure postponed- 1%

- Additional therapy- 1%

- Age did not predict abnormalities

- Abnormalities not associated with complications

This study concluded that screening of geriatric patients important and that sub-clinical disease could be present in nearly 30 % of these patients. The value of screening before anaesthesia is perhaps more questionable in terms of anaesthetic practice but it is an appropriate time to perform such an evaluation.

(Joubert, 2007)

- 100 cats > 6 years old

- Not pre-anesthetic screening, just general screening

- No know abnormalities on Hx

- Many not normal on PE

- Lots of abnormalities

- 13% increased wbc

- 29% increased creatinine

- 15% increased BUN

- 25% increased glucose

- 4% increased T4

- 6% increased ALT

Some new diagnoses

- 14% FIV positive

- 2% CKD

- 1% hyperthyroidism

- 1% UTI

- Relevance to pre-anesthetic screening?

- Some abnormalities were related to choice of reference interval

- Many abnormalities were clinically irrelevant

- Not truly screening since some had PE abnormalities

(Paepe, 2013)

4. Human Literature

a. Systematic Reviews

CBC

- Abnormal <1% to 5%

- Change protocol- 0.1% to 2.7%

Hemostasis

- Abnormal 3.8-15.6%

- Change protocol- rarely

Biochemistry

- Abnormal <1% to 5%

- Change protocol- rarely

Urinalysis

- Abnormal 1-35.1%

- Change protocol- 1% to 2.8%

The tests reviewed produce a wide range of abnormal results, even in apparently healthy individuals.

The tests lead to changes in clinical management in only a very small proportion of patients, and for some tests virtually never.

The clinical value of changes in management which do occur in response to an abnormal test result may also be uncertain in some instances.

The power of preoperative tests to predict adverse postoperative outcomes in asymptomatic patients is either weak or non-existent.

For all the tests reviewed, a policy of routine testing in apparently healthy individuals is likely to lead to little, if any, benefit.

The clinical importance of many of these abnormal results is uncertain.

(Munro, 1997)

b. Guidelines

- Don’t obtain baseline laboratory studies in patients without significant systemic disease (ASA I or II) undergoing low-risk surgery

- Performing routine laboratory tests in patients who are otherwise healthy is of little value in detecting disease.

- Evidence suggests that a targeted history and physical exam should determine whether pre-procedure laboratory studies should be obtained.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists

Bottom Line

- If you test, you will find abnormalities

- The clinical significance of these abnormalities is unclear

- You will find more abnormalities if pre-test probability is high

- Indication for test in Hx

- Abnormality on PE

- There is no evidence testing healthy patients reduces morbidity or mortality

What’s the harm?

- Expense

- Risk of testing

- Overdiagnosis

- Expense

- Stress

- Direct harm

References

Alef, M.; Praun, F. von; Oechtering, G. Is routine pre-anaesthetic haematological and biochemical screening justified in dogs? Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 2008 Vol. 35 No. 2 pp. 132-140

Munro J, et al. Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1(12):i-iv; 1-62.

Paepe D, et al. Routine health screening: findings in apparently healthy middle-aged and old cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2013 Jan;15(1):8-19.

Joubert K.E., Pre-anaesthetic screening of geriatric dogs. J S Afr Vet Assoc. March 2007;78(1):31-5.

Great article and website. I enjoy the rigorous nature of the science presented.

My question is, have you come across similar literature relating to greyhounds and pre-anaesthetic bloodwork? I have two greyhounds and am always nervous when they undergo surgery due to the different blood chemistry of greyhounds and their reaction to anaesthetic. I have even heard of bloodwork during surgery to watch for spikes in potassium levels that are often a precursor to cardiac arrest.

Thank you for your time.

I have not seen any literature specifically related to pre-anesthetic bloodwork in greyhounds or other sighthounds. They do have some know differences in their normal bloodwork values (higher packed red cell volume, for example). But most of the issues with anesthesia are related to body composition (less fat so slower redistribution of some agents) or anesthetic agents which are not widely used these days (barbiturates), and none of these would be influenced by bloodwork done before surgery in an individual patient. As for hyperkalemia (high blood potassium), that is not something typically monitored during anesthesia in dogs without pre-existing abnormalities in potassium identified before surgery.

Hah! So I was not entirely wrong in suspecting that nearly $100 worth of pre-operative blood testing amounted to a very padded bill for teeth cleaning (she did have an extraction, still…).

Beware of any preventative medicine promoted without prospective clinical trials showing they are needed. did they charge for teeth polishing? There is little science for polishing teeth after a dental cleaning from a health standpoint and polishing has some risk associated with it. There is insufficient evidence to determine the health effects of routine scale and polish. Polishing does remove stain from teeth so it’s a good idea from a cosmetic standpoint. If your mom gets alsheimer disease and needs sedation for dental cleaning the dentist will wait till the gums get infected before a cleaning. It’s considered unethical to clean her teeth before the gums get infected.

Interesting and concise summary.

Can I add the following study to your list:

http://www.banfield.com/getmedia/1216c698-7da1-4899-81a3-24ab549b7a8c/2_1-Healthy-Pets-benefit-from-blood-work

My main issue with pre-anesthetic bloodwork in asymptomatic patients is that it is a fishing expedition and if I was to accept the proposed logic behind it, then it would be the tip of a rather larger, and even more expensive, iceberg of pre-anaesthetic screening. For instance I would have thought that a Holter monitor and echocardiography would be as likely, if not more likely, to turn up relevant information on anaesthetic risk and potential mitigation of it than liver enzymes are ever going to be…

Finally, a morning urine sample is likely to be quicker, cheaper and at least as useful for screening for kidney disease.

In a setting where, unlike human hospitals, blood products are not handy, I can see a logic behind coagulation testing prior to major surgery as the consequences may be quite dramatic in the small percentage of cases where a defect in haemostasis is present. That said, unless its a Doberman I don’t check anything currently. I would certainly consider testing for fibrinolytic defects in Greyhounds prior to major surgery (eg limb amputation) if I was aware of reliable tests for predicting succeptibility to post-operative problems.

Thanks for the link. The data in the Banfield study certainly seems to me to undermine the argument of the article, which is that we should be doing this screening universally. Only 0.1% of pets screened had their procedures cancelled or postponed, and it is not clear how many of those ended up with lower morbidity and mortality than they would have had without the screening. A procedure which benefits one tenth of one percent of patients who have it is pretty difficult to justify without perfect safety (including no risk of overdiagnosis) and very low cost.

To look from another angle, there are 2 aspects of anesthesia safety that are more generally accepted that could be argued as justifications:

1) Redundency. It is common-place to take safety measures that should not be necessary on the basis that mistakes happen and if there are a number of redundent steps, then a series of mistakes must occur before a serious adverse outcome occurs. Pre-anesthetic blood screening could be considered a largely redundent step in anaesthetic safety and still be justifiable.

2) Maximising anesthetic safety. If we assume that the serious adverse outcome rate from general anesthesia in an apparently healthy dog is 0.1% WITHOUT pre-anesthetic blood screening, then it would be unrealistic to expect the additional “safety measure” of pre-anesthetic blood screening to result in changes to a much larger number of procedures. If introducing this halved the serious adverse outcome rate (I’m not saying it would), then that would be only a reduction of 1 serious outcome per 2000 blood tests. It is questionable whether other more generally accepted anesthetic “safety measures” looked at on their own achieve a more messurable reduction in serious adverse outcome rate; for instance the addition of pulse oximetry, or capnography, or ECG, or blood pressure monitoring in apparently healthy dogs etc.

>>>>. Pre-anesthetic blood screening could be considered a largely redundent step in anaesthetic safety and still be justifiable.

My wife is a nicu-u nurse. When the non invasive easy to use blood pressure monitors came out they were promoted to work in dogs and cats. I forked out a few thousand bucks and bought one. Over the next three years I took blood pressure readings on every pet that came in for Avma promoted “annuals” and every spay and castration that had no medical or behavior reason to be neutered. I think most of the pet blood pressure “experts” now agree what I was doing with my expensive blood pressure machine was pretty much a rain dance. I sure “believed”I was a superior veterinarian and clients said they were impressed with my extensive “uptodate” preventative medicine medicine. The Avma still promotes annual checkups are as important as water to pets. I was looking for something to do preventatively to justify my annual checkups. Back then I vaccinated annually for 7 diseases and did annual Heartworm and fecal checks on animals on solid parasite prevention. Studies show for dogs on solid Heartworm prevention must positive Heartworm test are false positive. I’m sure some dogs were treated with arsenic that did not have Heartworms since we did not have ultrasounds to see them. The vet blood pressure Experts now promote a new type of blood pressure machine is efficacious for pets. However is difficult to find a expert that wants to teach students when and how to use the new machines it unless the expert works for the company selling the blood pressure monitor. I “believe” doctors do more harm than good promoting annuals but part of my belief thinks that I am an exception when people want to bring their pet to me for a annual visit. I wonder if their are any vets who think they do more harm than good during a annual visit.

Interesting, Art!

At the risk of getting off topic, I sympathise with your position.

I think the usefulness of a physical examination in an apparently healthy patient is in a similar category to pre-anesthetic blood screening.

As a new-graduate, I prided myself on running what I considered to be a full physical examination on each patient in for a vaccination, and if funds had permitted would have excitedly drawn bloods to give baseline readings for that patient. Now I often muse that my laying on of hands (and the crucial reach for the stethoscope) is more for show than usefullness. I appreciate this may say more about my physical exam skills than anything else!

When I show students, I joke with them as I go: “lymphoma check, football-sized abdominal mass check” etc. The probability of doing any significant good by palpating a dog or cat’s lymph nodes or abdomen annually seems remote to me.

There certainly are things that I think I help with that wouldn’t be noted otherwise, but abdominal palpation and lymph node palpation have had an extremely low diagnostic yield in “healthy” patients in last number of years 😉

I get significantly more information from speaking to the owner than examining the pet. Indeed, a well-structred “App” or questionnaire would yield more benefits than my regular appointment slots do, I reckon.

As such, I’m pretty liberal with recommendations and try to keep the pet’s interests at heart. I think an annual visit to the vet is fine, but making that a pleasant experience and not subjecting the pet to an unecessary adverse experience primarily for show-purposes. We currently vaccinate annually for lepto where I am, but I don’t use the dog’s presence for a lepto vaccine as an excuse to perform a “full physical” on it unless to do so is at worst a “neutral” experience. If we didn’t do annual lepto vaccines, I would still consider it reasonable for an annual visit, but mainly for weight check and familiarisation with clinic in positive fashion.

We currently vaccinate annually for lepto where I am, >>>

I use to vaccinate for lepto and parvo every 6 months. When I graduated in 73 the teachers told us we had to vaccinate any dog admitted that had not been given a distemper shot within the last 6 months. Funny how our preventatives are all based on how long it takes the earth to go around the sun. . I have not seen any local hospital records where they were not still vaccinating for something annually at their annual exam. Some rotate the vaccines every year.

As always with medical interventions, diagnostic or therapeutic, the trick is to balance risks/costs and benefits. This is hard to do without data, and sadly in vet med we rarely have enough. Once we do, we can argue about whether or not a 50% relative reduction in risk that translates into an absolute reduction from 1:1000 to 1:2000 justifies the financial costs, the rare complications of venipuncture, or the potential risk of unnecessary followup tests done to investigate abnormalities identified in screening. Those are values decisions open to debate. But without enough data, we are just guessing at the risks and benefits.

The natural tendency is to screen “just in case,” almost no matter what. In human medicine, it is becoming more widely recognized that this sometimes leads to more harm than good in the population. The use of mammography screening for breast cancer and PSA screening for prostate cancer, for example, have been changed significantly since data became available that more people were being harmed than helped by some uses of these tests. And though we like to think cost shouldn’t be a factor, at least in human medicine it is accepted as a reality that we cannot ignore the financial burden on the healthcare system, which affects the cost and availability of healthcare, imposed by inappropriate diagnostic testing done “just in case,” even if some individuals do benefit from such testing.

In terms of the specific of pre-op bloodwork for healthy dogs and cats, I think a case certainly can be made for it, and the arguments you mention are part of that. The fact that our patients cannot disclose early symptoms, and owners don’t always recognize them, is also one of the main justifications for the use of screening tests that might not be appropriate in people. Still, I think we lack much of the data needed to effectively weight costs and benefits. I have simply tried to collect what there is regarding the potential benefits so people can appreciate that they are probably smaller than we often think. I have no knowledge of any sources of data about the costs, financial or in terms of risk and stress associated with unnecessary followup testing, so it’s hard to really evaluate the issue objectively.

At least I think it fair to view the data we do have as undermining the claim, often made, that preoperative bloodwork is the standard of care and that not doing it is somehow substandard medicine. I found the Banfield article particularly interesting since it identified the detection of a miniscule number of abnormalities as strong justification for the practice without considering the risks or costs of the procedure. I also cannot help but consider that there is a great deal of profit to be made by making such testing mandatory and declaring it the standard of care to justify this even when it almost never alters the anesthetic plan, and this might be a factor in the conclusions of that article.

Interesting perspective. I feel rather differently about the physical exam, and I find new grads are often far too eager to recommend imaging or clinical lab diagnostics when the problems they are looking for can be either identified or ruled out to a large degree by the physical exam. I agree that the history is critical, and often more sensitive than the PE, but I find clinically relevant problems all the time that the owner had not noticed or considered important by doing a thorough PE rather than just focusing on what the client brought the pet in for. In any case, the PE is about the lowest risk and lowest cost diagnostic we offer, so again when balancing the benefits of it against the risk and cost, I would bet it outperforms a lot of higher-tech diagnostics.

As for frequency of visits, I do think that’s pretty arbitrary. I do recommend regular visits for well pets because I feel like I see changes that owners don’t notice, things like weight loss or dental disease, etc. But why annually? If anything, it would seem like more frequent visits, with frequency tied to age or previous medical history, might make more sense, but how would we decide on the most appropriate interval? We have lots of data on appropriate vaccine frequencies (which I talk about elsewhere), but it’s hard to find anything on the results of regular visits and exams.

Thanks for all the information and insight. By chance I am a “human” anesthesiologist, and one of our dogs (healthy, age 5) is scheduled for relatively minor orthopedic surgery to help with a limp she has developed- inference being she is in pain, and the surgery hopes to improve her quality of life. Of course she is scheduled for prep lab testing- something we don’t do in healthy humans, for the exact and well-put reasons you describe. I can get nowhere with the vet hospital or surgeon about cancelling the tests. My main observation is that if anything, the testing paradoxically make me less confident in the surgery. Do they really know what they are doing? Are they just doing all of it for the money?

Actual quote from a fellow physician- “it’s not anecdotal, I’ve had cases…”

I wouldn’t judge the vets too harshly. Pre-operative blood testing has been heavily promoted as “standard of care” for a while now, and it is difficult to stand up against that when people are implying you don’t care about the welfare of your patients if you don’t recommend it. A survey on a popular internet forum for vets asked >2,000 about the time frame in which they required pre-anesthetic bloodwork, and only 3% admitted they didn’t require it. Financial bias is one factor, but for most it’s more about being perceived as doing “everything you can” for the safety of patients.

The intentions are good, but there is an absence of data that would allow us to identify overdiagnosis, so screening tests of all kinds are still viewed as an unquestioned goo in vet med. I am trying to get a paper published challenging that notion, with this kind of testing as an example, so maybe the discussion will eventually move forward.

I am trying to get a paper published challenging that notion,>>>>>

I did a prospective randomized study with my pets to see if it is true, as the AVMA asserts. that Annual pet exams are as important as water to pets. In the study I gave all my pets a annual exam and water day one. By day two i had to stop the study because the half of my pets that got annual exams but not water were getting dehydrated. Do you think i could get the avma to publish my study?

All kidding aside is the peer review publishing system in vet med broken in your experience? What ever happened to the metronidazole pet diarrhea study you were doing?

The metronidazole study was supposed to be my MSc thesis, but I couldn’t get funding and ultimately couldn’t conduct a prospective RCT as my thesis project in the time available. Instead, I did a systematic review looking at reporting quality and risk of bias in veterinary clinical trials. That will hopefully turn up somewhere in the next year. It certainly suggests that the quality of trials is pretty poor, which doesn’t speak highly of the peer=review system. But that’s not much different from the situation in human medicine, for a change. AllTrials and VetAllTrials are efforts to deal with the problem, so we’ll see where they go.

Any enterprising young researchers wanting to find a trove of data to mine in a pet population where surgeries (spay/neuter) are routinely performed without bloodwork can probably find it at public animal shelters and high-volume/low-cost spay/neuter clinics. Thousands of surgeries are performed a year in most mid-size or larger cities, and pre-surgery bloodwork is almost never done. In the Deep South, this includes populations of HW+ dogs (who are routinely spayed/neutered by shelters and rescues before getting HW treatment, and they do just fine).

The shelter medicine protocols for spay/neuter seem to be different than the private clinical protocols, but the outcomes don’t seem to be any different.

It’s true that complication rates for shelter neuters are quite low. I’m not aware, though, of data directly comparing these to the same surgeries in private clinics, so I don’t think we can confidently say there is no difference in complication rates. Also, bear in mind shelter neuters are on young, almost always healthy animals. That’s quite different from the majority of surgeries done in private practice, which are often old or ill, so that might affect the relevance of pre-anesthetic bloodwork. I do think studies looking at the difference between doing and not doing bloodwork before surgery on shelter animals in terms of surgical outcome, survival (would they euthanize those with abnormalities?), adoption, etc., would be really interesting.

I’d love to know what the pre or post blood values are ,or were, for the many really toxic pyos and aged cats with grotty mouths, not to mentin the very blocked cats [and the emphasis on K+….]

Both groups always sailed through their major procedures without any signs of a deterioration in their serious preop state.

My experiemce is the adverse anaesthetic or surgical experience is the fit healthy labrador or cat spay that dies on induction…..