About two years ago, Mark Crislip over at Science-Based Medicine wrote about an article that had a profound impact on his practices as an M.D. specializing in infectious disease, Observations on Spiraling Empiricism. He recently mentioned this article again on his own infectious disease blog, which drew my attention to his earlier post and the original article. I strongly encourage anyone who has an interest and access to the medical literature to read the original article. Though it focuses particularly on empirical antibiotic therapy (that is, using antibiotics when an infection of some kind is suspected but no specific diagnosis is made), it provides an excellent general conceptual approach to therapy and an eloquent and cogent description of the dangers of initiating therapy in the absence of a definitive diagnosis or even a single prime suspect.

This problem is even more acute in veterinary medicine, where we have fewer resources and less detailed knowledge about our patients’ diseases. Even the case examples in the article which illustrates mistakes in medical decision making often have far more meticulous and thorough analysis done than we veterinarians can do at our best. The risks of acting on incomplete information are likely even greater for us since we are more often forced to do so and our information is often exponentially less comprehensive than that our MD colleagues have to work with.

The article begins by acknowledging that antibiotics have been a phenomenally successful medical therapy that have done by far more good than harm, and that advances in the drugs available since the first penicillins and sulfa drugs of the 30s have made them ever safer and more effective. It is important, especially when dealing with the pharmacophobia of much of the alternative medicine community, not to lose sight of the historical context when examining some of the problems with these drugs and how they are used.

The authors then state clearly, and with an unusual literary flair, the nature and complexity of the problem with inappropriate antibiotic use.

The imprecision of clinical practice establishes the context; the litigious nature of society unnerves; the absence of toxicity permits; and the sum of these encourages the incontinent, extemporaneous use of antimicrobial agents…

The term spiraling empiricism describes the inappropriate treatment, or the unjustifiable escalation of treatment, of suspected but undocumented infectious disease. Empiricism and empirical therapy, defined as the carefully considered, presumptive treatment of disease prior to establishment of a diagnosis, often are necessary in the proper practice of medicine. On the other hand, ill-considered or inappropriate use of antibiotics, incurring unnecessary risk and expense, should be indicted and condemned. The difficulty lies in distinguishing reasonable or appropriate from unreasonable or inappropriate therapy.

I would suggest that in veterinary medicine the role of “imprecision” is relatively greater and the role of litigation relatively smaller in driving inappropriate use of antibiotics, or indeed any therapy, but the general problem is broadly similar to that in human healthcare.

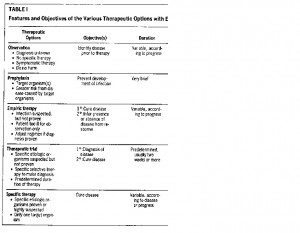

The article then presents a simplified conceptual framework for the options available to a clinician faced with the possibility of infection in a given patient. The examples (which I have omitted) are specific to human medicine, but the general approach is easily applicable to veterinary medicine, and provides a lot of insights into where medical decision making can go wrong.

The first option, Observation, is often the hardest for both vets and clients. So many diseases get better without intervention (which is why so many ineffective therapies appear to work), but without being able to predict which will and which won’t, it is very hard to simply wait and see. There are, of course, clear reasons not to simply observe in many cases: the severity of the symptoms, the likelihood of specific diagnoses which are less treatable when treatment is delayed, and many other factors. But just as we don’t (or shouldn’t) go to our doctor and demand antibiotics for every little viral respiratory infection, since the drugs have risks and costs and won’t help anyway and since we will almost certainly get better on our own, so we as doctors should resist the temptation to treat illnesses that are mild and likely to get better on their own (feline upper respiratory viruses, mild acute diarrhea, low-grade fevers in otherwise normal patients, etc).

And not only should we resist the temptation to treat these patients with antibiotics or anti-inflammatories without a sound rationale for doing so, we should resist the temptation to pretend to treat them with “safe and natural” remedies that are likely to do nothing other than create the false impression we’ve fixed something when the patients spontaneously get better (homeopathy, energy medicine, many vitamins and supplements, etc).

Preventative use of antibiotics is a bit clearer an option, though it is still important to base our prophylactic use of these medications on sound evidence that they are needed. The prophylactic use of antibiotics in dogs with heart murmurs undergoing dentistry, for example is a commonly accepted practice, yet there is some evidence that it may be unnecessary. There are also other studies which cast doubt on the effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotic use before some kinds of surgery, so we must be careful not to indiscriminately use such drugs “just in case” or to compensate for poor surgical technique unless there is sound evidence to support the practice. Nothing with a benefit is without risks and costs, and we must balance this equation as carefully as possible given the available information.

Empiric Therapy, as defined above, is a common practice. Given some indication of an infection (fever, increased white blood cell count, etc), but before the necessary steps have been taken to establish a true diagnosis (or, unfortunately, in some cases instead of taking these steps), antibiotics are given to treat a range of possible causes of the clinical symptoms. This can be a mistake in a simple and direct way if the patient doesn’t have an infection but develops an adverse reaction to the antibiotics. However, a less obvious pitfall with this kind of approach is the possibility of delaying or missing the true diagnosis, especially when the symptoms improve after the drugs are given and we assume, sometimes mistakenly, that the drugs are responsible and that our suspicions of infection were correct. This post hoc ergo propter hoc bedevils us in medicine all the time, and this is one of the most common circumstances in which it does so. Just because we do something and the patient’s condition changes, it is not automatically true that we deserve the credit (or blame) for the change.

Empirical Therapy is distinct from a Therapeutic Trial, in which a specific infection is suspected and a specific antibiotic treatment is begun with the patient’s response used to support or contradict the presumed diagnosis. The difference is that the odds of a this-then-that relationship in time reflecting a true causal relationship is greater if there is a reasonable prior probability, based on factors other than the treatment, of there being such a relationship.

In a simpler example, if a dog has a cough and a chest x-ray shows a mass in the lung, the chance that the mass is truly relevant is fairly high. But if a dog with diarrhea has a chest x-ray that shows a mass, there is little reason to think the x-ray finding is relevant to the symptoms. A relationship between a potential cause and an effect is more likely to exist if there are multiple different lines of evidence supporting such a relationship. So if all the clinical symptoms are classic for a particular bacterial infection, and the symptoms go away on an antibiotic sited to that organism, then a cause/effect relationship between treatment and response is fairly likely. However, if the symptoms (such as a fever) could be due to any of a hundred diseases, and the symptoms go away after treatment for one of them, we cannot confidently use this fact to conclude the patient had that one disease.

Of course, even a therapeutic trial can lead to an erroneous conclusion. I once treated a young dog with a fever, neck pain, and a high white blood cell count with antibiotics, under the reasonable suspicion that it had an infectious meningitis (the owner declined the invasive and expensive tests to confirm my suspicion). The patient got better and I basked in the glow of my own self satisfaction. Until a few months later when it came back with the same signs and didn’t get better on antibiotics. Eventually, it became clear that the pet had symptoms every time it came into heat, and that it was a non-infectious immune-mediated meningitis which responded to steroids. Once the dog was spayed it never recurred.

Finally, Specific Therapy is treatment of a particular disease we have actually diagnosed. Obviously, this is far more likely to be effective and to have a positive benefit to risk ratio than relatively blind empirical therapy.

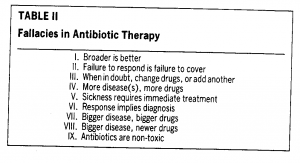

The authors then go on to list a number of misconceptions doctors have about empirical antibiotic therapy, which again could apply just as well to many other kinds of medical intervention.

In his discussion of the article, Dr. Crislip expands on each of these fallacies, and adds a couple. Some of his comments are worth reproducing here.

When in Doubt, Change Drugs or Add Another

Medicine is filled with uncertainty, and often it is the case that if an infection is thought of, it is treated, no matter how unlikely it is that it may be causing the disease. I have a fantasy where oncology is practiced like infectious disease. “It might be lymphoma, so lets start with CHOP, but we don’t want to miss adenocarcinoma, so lets add bleomycin, and in case its breast cancer we need to include tamoxifen and if could be prostrate so lets add etc , etc.”

When in doubt, increase your diagnostic certainty.

Response implies diagnosis

This is the most difficult fallacy for people to abandon. Patient has a fever, no diagnosis is evident, but the fever went away at some point after the institution of antibiotics.

Most fevers go away. Many diseases that are not infectious will have a fever. This is the medical equivalent of the skeptical motto ‘association is not causation’. The worst cognitive error physicians and patients make is the assumption, the Rigorously absence of a good diagnosis, that the improvement when a therapy is given is due to the therapy.

Rigorously and consciously avoiding this error is key to being a good health care provider.[emphasis added]

Some antibiotics are a big gun, are strong, or powerful

There are few things in medicine with 100% sensitivity and specificity. However, if your health care provider uses the adjectives big gun, strong, or powerful in reference to an antibiotic, they are either 1) talking out their backside or 2) ignorant about antibiotic use. 100% sensitive and specific

If I had neurosyphilis…, the ‘strong’ or ‘powerful’ ciprofloxicin would do nothing to treat my infection, put ancient, weak old penicillin remains the treatment of choice. What you want is to give are appropriate antibiotics: something that will reliably kill the organisms in whatever space is infected. These adjectives are advertising ploys used on fool gullible rubes, er, I mean health care providers, to think they are doing what is best for their patient. They provide a false security that you are giving the patient the best therapy.

The primary reason a particular antibiotic is given is that “I like it.

I like to say that the three most dangerous words in medicine, especially when it comes to therapeutic interventions, are “In my experience.” In my experience you can’t trust anyone who uses that phrase. Remembering hits and forgetting misses drives antibiotic use more than I would like to admit. Infectious disease docs are sometimes the opposite. We put too much emphasis on the antibiotics that have failed us in the past. It is o e extreme or the other.

Patient is admitted with a complicated infection and started on X. Why X? I ask. It worked for me in the past is the reply. What are you trying to kill? I might then ask. Often, they say the boogie man of the ICU, Pseudomonas. What I will continue, is the chance drug X will be effective against Pseudomonas? They don’t know. So why again are you using X? It is what we do. They have used it successfully in the past, so it should work again.

Sigh.

Fortunately, most drugs work most of the time in most patients, but that rule is slowly being lost as the organisms become increasingly resistant to our current armamentarium of antibiotics and there are few, if any, replacements in the pipeline. At my institution there is 2% resistance for Pseudomonas to Ceftazadime and 4% to pipercillin/tazobactam. We get a few cases a year at best of a blood stream infection and sepsis from Pseudomonas. Most physicians are not going to see enough infections by a given organism to get a sense of what does and does not work. It is why you cannot trust your experience.

And finally, what could easily be a motto for the whole project of evidence-based medicine:

But often getting the right diagnosis and therapy is less about what you know and more about being rigorous about understanding how you know. Only when you are conscious of your ability to think poorly, can you compensate.

References

1. Kim JH, Gallis HA. Observations on spiraling empiricism: its causes, allure, and perils, with particular reference to antibiotic therapy. Am J Med. 1989 Aug;87(2):201-6.

See the movement by the profession toward annual testing and antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic animals.

http://www.lymeinfo.com/case2.aspx

art malernee dvm

Pingback: A Primer on Medical Cognition | The SkeptVet