I recently gave a lecture at the Western Veterinary Conference called “What You Know that Ain’t Necessarily So.” The purpose of this was to take some common or controversial beliefs and practices in veterinary medicine and discuss the scientific evidence pertaining to these. This was not intended as a definitive, “final word” on these subjects, but as an illustration of how weak and problematic the evidence often is even behind widely held beliefs. In some cases, these practices or ideas may actually be valid, but without good quality scientific evidence, we should always be cautious and skeptical about them.

Eventually, I will post recordings of the presentations themselves, but for now I am posting a summary of each topic.

Each starts with a focused clinical question using the PICO format.

P– Patient, Problem Define clearly the patient in terms of signalment, health status, and other factors relevant to the treatment, diagnostic test, or other intervention you are considering. Also clearly and narrowly define the problem and any relevant comorbidities. This is a routine part of good clinical practice and so does not represent “extra work” when employed as part of the EBVM process.

I– Intervention Be specific about what you are considering doing, what test, drug, procedure, or other intervention you need information about.

C– Comparator What might you do instead of the intervention you are considering? Nothing is done in isolation, and the value of most of our interventions can only be measured relative to the alternatives. Always remember that educating the client, rather than selling a product or procedure, should often be considered as an alternative to any intervention you are contemplating.

O– Outcome What is the goal of doing something? What, in particular, does the client wish to accomplish. Being clear and explicit, with yourself and the client, about what you are trying to achieve (cure, extended life, improved performance, decreased discomfort, etc.) is essentially in evidence-based practice.

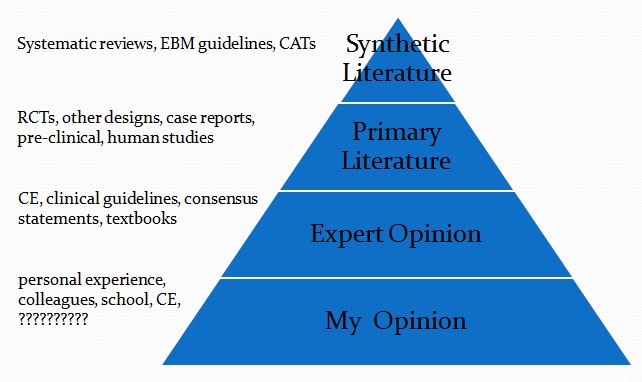

This is then followed by a summary of the evidence available at each of the levels in the following pyramid (which is a pragmatic reinterpretation of the classical pyramid of evidence that is a bit more useful for general practice veterinarians).

Finally, I list the Bottom Line, which is my interpretation of the evidence.

- Clinical question

P– dogs with naturally occurring mitral valve disease (MVD)

I– angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) before onset of congestive heart failure (CHF)

C– no ACE-I before onset CHF

O– time to CHF, survival

2. Synthetic Veterinary Literature

a. Systematic Reviews- none

b. Critically Appraised Topics (CAT)-

Best Bets for Vets

Benazepril in dogs with asymptomatic mitral valve disease

(1 study, significant weaknesses)

There is insufficient evidence to suggest that dogs with asymptomatic mitral valve disease treated with benazepril will live longer.

3. Primary Veterinary Literature

Long-term treatment with enalapril in asymptomatic dogs with MVD and MR did not delay the onset of heart failure regardless of whether or not cardiomegaly was present at initiation of the study.

(Kvart, 2002) SVEP: Scandinavian Veterinary Enalapril Prevention Trial

Chronic enalapril treatment of dogs with naturally occurring, moderate to severe MR significantly delayed onset of CHF…Improvement in the primary endpoint, CHF-free survival, was not significant. Results suggest that enalapril modestly delays the onset of CHF in dogs with moderate to severe MR.

- No difference in primary endpoint (time to CHF)

- Questionable secondary endpoint (all-cause mortality)

- Selective exclusion of some subjects from analysis

- Questionable selection of time points for comparisonBNZ had beneficial effects in asymptomatic dogs other than CKC and KC affected by MVD with moderate-to-severe MR.

(Atkins, 2007) VETPROOF

- No difference overall in development of CHF or “cardiac events”

- Questionable endpoints (all-cause mortality)

- Differences between groups in disease severity

(Pouchelon, 2008)

4. Human Literature-

a. Systematic Reviews

CE inhibitors…reduced the RF, RV, and left ventricular size by a modest degree in chronic primary MR.. and may offer a pharmacologic treatment option to delay the deleterious hemodynamic effects of left ventricular volume overload.

(Strauss, 2012)

b. Guidelines

- In the asymptomatic patient with chronic MR, there is no generally accepted medical therapy.

- There has not been a consistent improvement in LV volumes and severity of MR in the small studies that have examined the effect of ACE inhibitors.

- in the absence of systemic hypertension, there is no known indication for the use of…ACE inhibitors in asymptomatic patients with MR and preserved LV function.

- If LV systolic dysfunction is present, primary treatment of the LV systolic dysfunction with drugs such as ACE…[has] been shown to reduce the severity of functional MR

- (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, 2006)

Bottom Line–

- Research is conflicting

- Cardiologists disagree

- Critical review of the evidence does not suggest ACE-I

- Delay onset of CHF

- Prolong survival when begun before CHF

References

Atkins CE, et al. Results of the veterinary enalapril trial to prove reduction in onset of heart failure in dogs chronically treated with enalapril alone for compensated, naturally occurring mitral valve insufficiency. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007 Oct 1;231(7):1061-9.

Kvart C, et al. Efficacy of enalapril for prevention of congestive heart failure in dogs with myxomatous valve disease and asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2002 Jan-Feb;16(1):80-8.

Pouchelon JL, et al. Effect of benazepril on survival and cardiac events in dogs with asymptomatic mitral valve disease: a retrospective study of 141 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2008 Jul-Aug;22(4):905-14.

Strauss CE, et al. Pharmacotherapy in the treatment of mitral regurgitation: a systematic review. J Heart Valve Dis. 2012 May;21(3):275-85.