Over the years, I have written a lot about how we come to hold and maintain false beliefs in medicine. Perhaps the lion’s share of this lies in anecdotes, which are powerfully persuasive despite all the sources of bias and error they contain that actually make their conclusions highly unreliable. Here are some of the articles I have posted making this point:

Why We’re Often Wrong Testimonials Lie

The Role of Anecdotes in Science-Based Medicine

Why We Need Science: “I saw it with my own eyes” Is Not Enough

Don’t Believe your Eyes (or Your Brain)

However, scientific research, while more trustworthy than our personal experiences and the stories we tell, can also be misleading and influenced by many of the same sources of cognitive bias and error that bedevil anecdotes and clinical experience. I have written about this subject before:

Can We Trust Published Scientific Research?

I recently came across a brilliant paper that illustrates how clinical trials, one of the best single tools available for evaluating medical treatments, can be misused to generate the appearance of scientific support for treatments that don’t actually work. The practices described in this paper are all too common in every area of medical research. Sadly, they are especially prevalent in veterinary clinical studies. And the paper provides an almost perfect description of the great majority of research done in complementary and alternative medicine, which is why so much of the literature in that field is truly more marketing than good science.

As I have argued before, this is often the explicit intent of researchers promoting alternative therapies, such as the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association and its affiliates. However, the misuses of clinical trials, and of statistical analysis of trial data is unfortunately a blight on mainstream medical research as well. Everyone interested in the truth in medicine would do well to read this paper.

Cuijpers and I. A. Cristea How to prove that your therapy is effective, even when it is not: a guideline. Epidemiology andPsychiatric Sciences, Available on CJO 2015 doi:10.1017/S2045796015000864

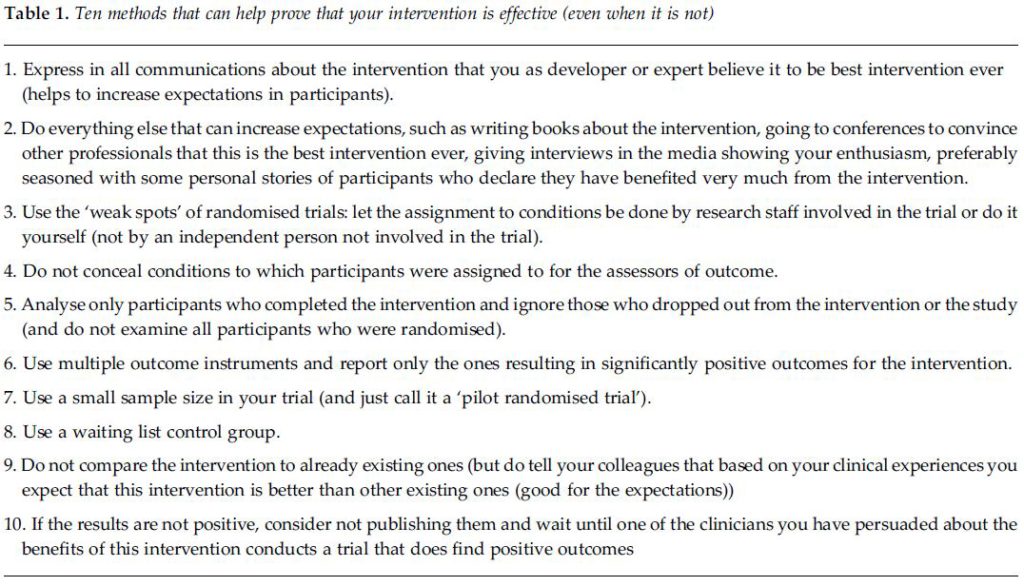

The authors describe, clearly and in an engaging way, many practices in clinical trial design and conduct that can lead to false positive conclusions. Most are driven, ultimately, by the passionate belief of researchers in the a priori truth of their hypothesis. The following table succinctly describes the major issues.

Their conclusions are equally succinct and worth bearing in mind when conducting or reading clinical trial research.

In this paper, we described how a committed researcher can design a trial with an optimal chance of finding a positive effect of the examined therapy….We saw that a strong allegiance towards the therapy, anything that increases expectations and hope in participants, making use of the weak spots of randomised trials (the randomisation procedure, blinding of assessors, ignoring participants who dropped out, and reporting only significant outcomes, while leaving out non-significant ones), small sample sizes, waiting list control groups (but not comparisons with existing interventions) are all methods that can help to find positive effects of your therapy. And if all this fails you can always not publish the outcomes, and just wait until a positive trial shows what you had known from the beginning: that your therapy is effective anyway, regardless of what the trials say.

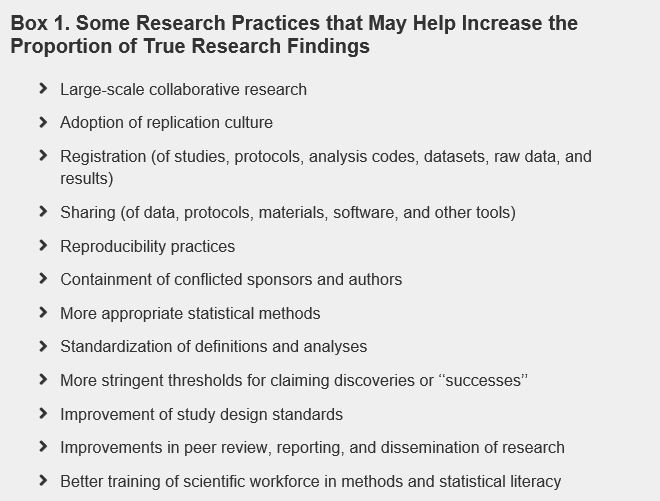

Of course, whenever the weaknesses in scientific research are discussed, this provides an excuse for some to claim that science is inherently unreliable, or at least no more reliable than anecdote or personal experience, and thus we can safely do without clinical trial research. It is very important for us to understand that this is untrue. The purpose of identifying the weaknesses in science is to help find ways to make scientific research better and more reliable. It has already proven itself greatly superior to trial-and-error and anecdotal evidence.

Lest we despair, there here are some previous discussions about the ways in which we can improve scientific research, including choosing what to study more rationally, designing, conducting, and reporting trials more effectively, and minimizing the influence of financial bias.

Evidence-based Medicine Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

Making Medicine Better: Support Registration of All Trials in Veterinary and Human Medicine

Guidelines for Minimizing Commercial Influence in Veterinary Medicine

Ioannidis JPA (2014) How to Make More Published Research True. PLoS Med 11(10): e1001747.