This post is a bit outside the usual topics I discuss on this blog, and I have no doubt I will get angry responses and admonitions to “stay in my lane.” But at a time when America is, once again, being forced to confront our long-standing failure to deal effectively with racial inequities built into our society and institutions, I feel an obligation to address the reality that veterinary medicine is very much a part of this problem.

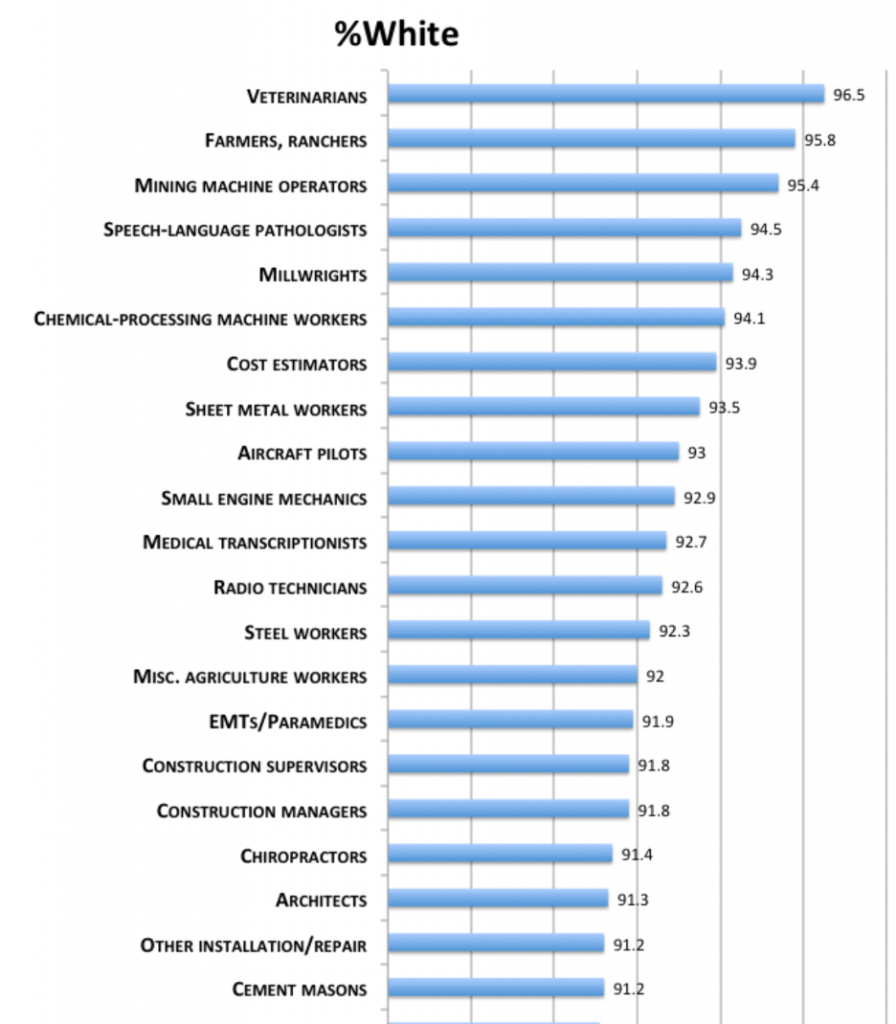

The facts are relatively straightforward: Over 95% of veterinarians are white in a country where about 80% of the workforce is white. Imagining this is an accident rather than the result of systemic racism is naive or disingenuous. Acknowledging an injustice is critical to rectifying it, and we cannot shy away from clearly and directly describing an unjust reality if we seriously hope to change it. Veterinary medicine is quite possibly the whitest profession in America, and this is like any problem in that we won’t be able to fix it if we don’t acknowledge it.

A common first reaction when a group of mostly white people is asked to consider the issue of racism within their community is defensiveness. There is a misconception that racism is limited to explicitly bigoted and discriminatory behavior by individuals who openly dislike people of color, and since few of us fit that caricature, it is easy to dismiss our own role in perpetuating racial inequities. However, racism is typically more insidious and systemic than this. It is not a problem of a few “bad apples” but a feature of how the barrel is built and maintained.

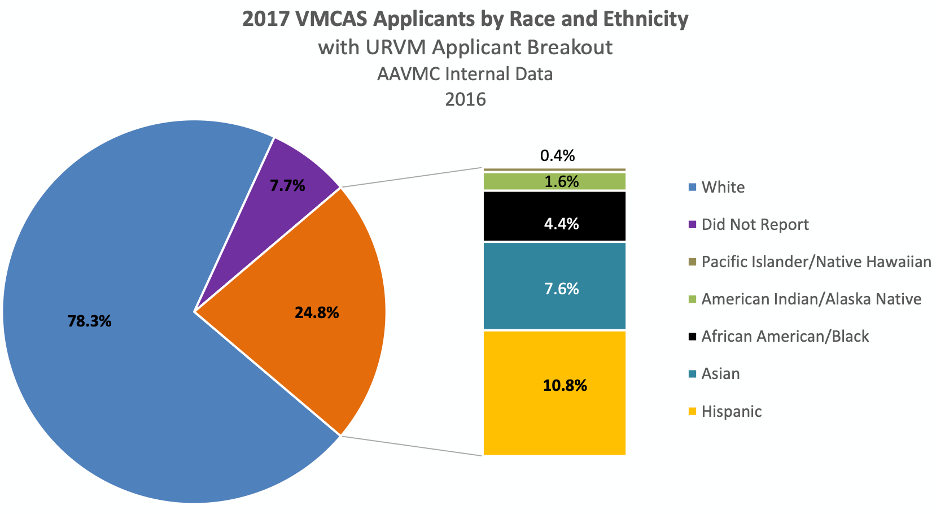

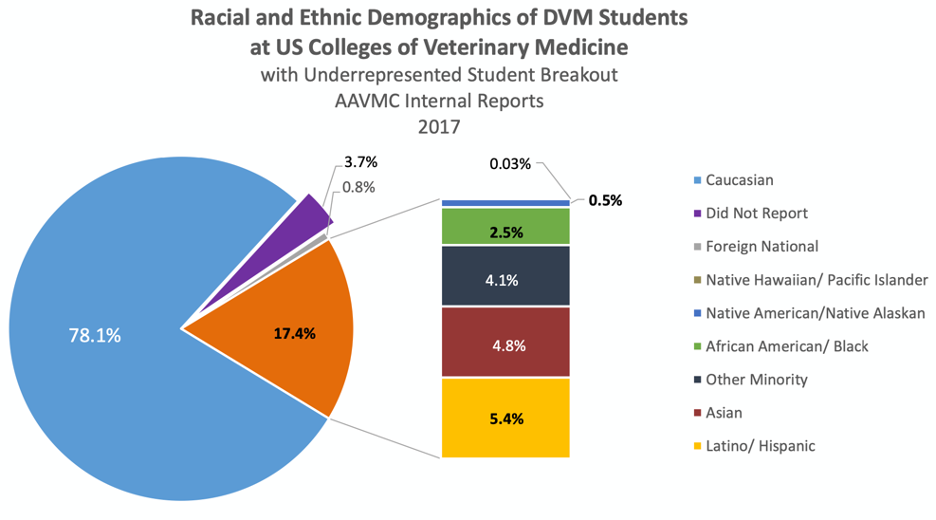

As an example, AAVMC data shows that the proportion of white applicants to veterinary colleges in 2016 (78.1%) was roughly the same and the proportion of white students in those colleges (78.3%). This suggests that explicit racial discrimination in admissions is not a major barrier to recruiting underserved groups into the veterinary profession. This is encouraging both because such discrimination would reflect poorly on the profession and because it would be a clear violation of federal law.

However, despite this, the representation of individuals from some underrepresented groups in both the applicant pool and as students in veterinary colleges is still dramatically lower than the proportion of the population identifying as members of these groups. For example, African Americans make up about 17% of the U.S. population but only 4.4% of applicants and 2.5% of veterinary students. The situation is actually worse than it sounds because about 70% of black veterinarians are educated at one school: Tuskegee University College of Veterinary Medicine, a historically black college. The underrepresentation of African Americans in veterinary medicine has persisted despite discussion about it and efforts to remedy it going back to the 1970s, and it is evident that there are strong and pervasive systemic factors behind this.

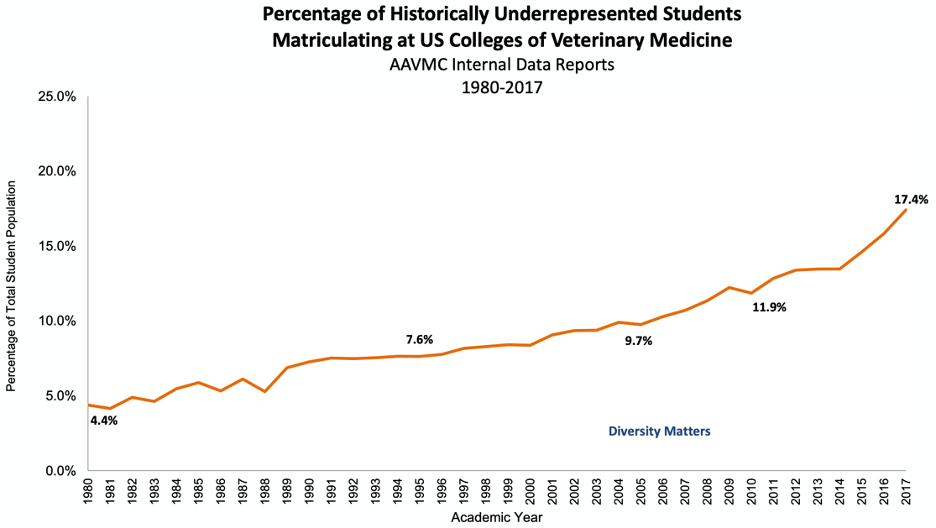

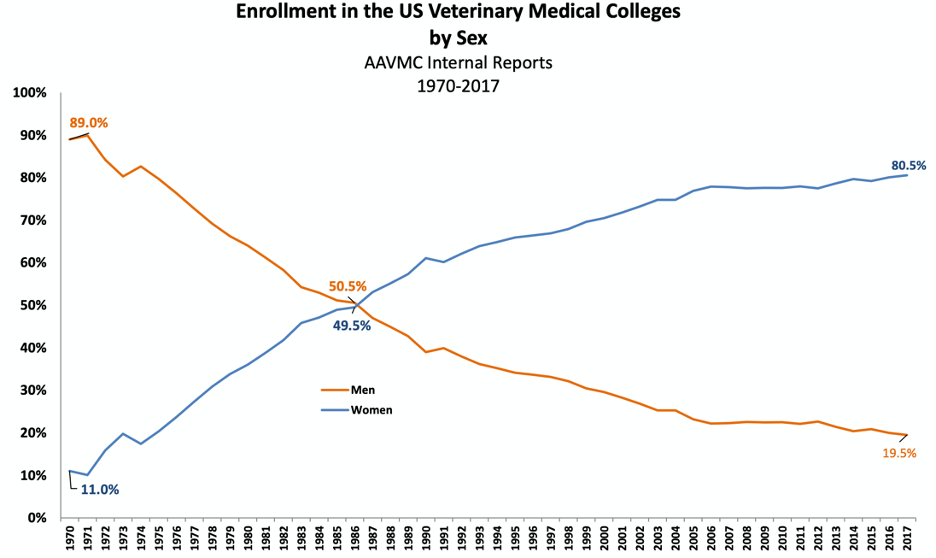

There have been some successes in addressing discrimination in veterinary medicine. Historically underrepresented groups have increased as a proportion of the student population.

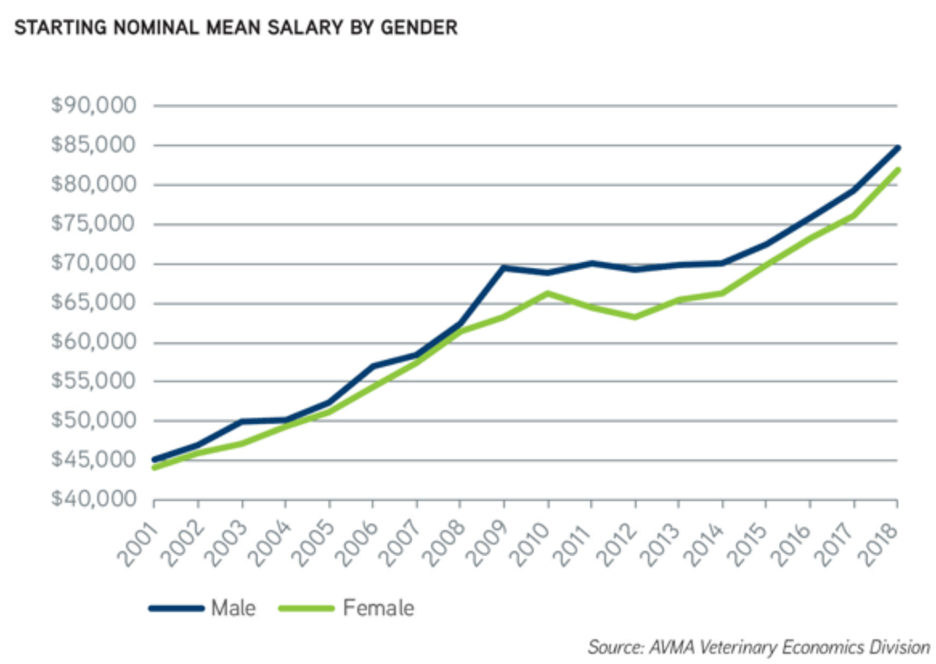

Women, in particular, have gone from a small minority to a large minority in veterinary schools, and they are now a majority in the profession and beginning to achieve parity in some areas, such as leadership roles at veterinary schools, though there are still disparities in pay and other indicators of equity.

We have actually reached a point where the overrepresentation of women in some areas of veterinary medicine is problematic. Contrary to a common assumption, diversity is not inherently a concept intended to exclude white people or men, and true diversity in the profession requires a better balance than currently exists in the gender representation among veterinarians.

However, it is important to remember that the historic underrepresentation of women in the field was the result of both individual and systemic discrimination, and the influx of women into the profession can be seen, at least partially, as evidence of effective strategies for combatting this. The underrepresentation of men in veterinary schools today, on the other hand, seems unlikely to represent the same kind of discrimination since it is implausible that a group still in a position of privilege and power in most areas of American society would somehow be excluded by deliberate or systemic discrimination in one small domain like veterinary medicine.

There are likely complex factors involved in the decline in male applicants to veterinary schools, and many of these may involve the ways in which the profession is portrayed and perceived in the culture as well as economic factors. For example, as veterinary medicine has shifted from a focus on food and working animals to companion animals, it may be seen more as a caring or nurturing profession which cultural stereotypes classify as more appropriate for women (women are also overrepresented in pediatrics and nursing, for example). Veterinary medicine is also among the lowest-paid of the medical professions, and men may be more likely to pursue higher-paying jobs (female-dominated professions in general tend to pay less than male-dominated occupations). The growing scarcity of male role models, at least in companion animal medicine, may also be a contributing factor.

The issue of gender representation is relevant to the subject of racism in veterinary medicine both as an example of how historic discrimination can be overcome and also how complex and indirect the factors influencing the recruitment of different groups into the profession can be. The underrepresentation of African Americans in veterinary medicine, for example, is sometimes written off as a lack of interest. This narrative suggests that black people aren’t as interested in animals as white folks and so are less likely to want to be veterinarians. The issue of cultural differences in attitudes towards animals is a real and complex one, but as a facile way of denying racism as a cause for underrepresentation of African Americans in veterinary medicine, it is not convincing.

For one thing, this doesn’t explain the consistent underrepresentation of other minority groups, such as the Latinx community. The idea that multiple historically marginalized groups all just happen to not be interested in veterinary medicine is not plausible. More likely, the paucity of applicants from underrepresented groups is related to a lack of examples and role models from those communities that make the profession seem welcoming and possible for them, the disadvantages such groups face in terms of education quality and opportunity well before veterinary school, the rising cost of a veterinary medical education, and a constellation of other factors. Such factors have certainly been demonstrated to be associated with underrepresentation of African Americans, for example, in other professions, and addressing these barriers has improved diversity in these cases.

Clearly, we have a lot of work to do as a profession if we are committed to real diversity. White people must take an active part in this work, leveraging our power and privilege no support equity and improve opportunities for those who have been, and still are denied then. We must remember that diversity is not a zero-sum game in which one group must “lose” for others to succeed. No one, least of all people of color, is suggesting lowering standards or implementing some sort of active “reverse discrimination” against white people. The goal is to ensure that everyone has a chance to explore and fulfil their potential, and that barriers to this which apply disproportionally to historically marginalized groups are removed. Diversity ultimately benefits the profession and all of us in it.

As a relatively old, white, male veterinarian, I can acknowledge the injustice that has favored those like me without feeling that the effort and struggles I endured to get where I am are being invalidated. I may be good at my job, and I may have earned my place through hard work. But many people who are just as talented, just as hardworking, and who have even greater obstacles before them are as deserving but have been denied the opportunities I have had. There is no question that being white has been an advantage in my journey. It does not diminish me to acknowledge this, but it does engender a responsibility to contribute to a more just future.

Resources-

Navigating Diversity and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine; 2013, edited by Lisa M. Greenhill, Kauline Cipriani Davis, Patricia M. Lowrie and Sandra F. Amass

Minority Student Perceptions of the Veterinary Profession: Factors Influencing Choices of Health Careers; 2008, by Dr. Evan M. Morse (thesis)

Unity Through Diversity; 2006, Final Report of the AVMA Task Force on Diversity

Cultural Competence in Veterinary Practice. V.Kiefer, K. Grogan, J. Chatfield, J. Glaesemann, W. Hill, B. Hollowell, J. Johnson, D. Kratt, R. Stinson, and K. Urday. JAVMA. 2013 243:3, 326-328

A Business Case for Diversity and Inclusion: Why it is Important for Veterinarians to Embrace our Changing Communities. L Kornegay. JAVMA. May, 2011.

Cultural Competence Education; Association of American Medical Colleges. 2005

The Attitudes of Minority Junior High and High School Students toward Veterinary Medicine. A. Asare. J Vet Med Educ. 2007 34(2): 47-50.

Tying Art and Science to Reality for Recruiting Minorities to Veterinary Medicine. PM Lowrie. J Vet Med Educ. 2009 36(4):382-387.

Racial, Cultural, and Ethnic Diversity within US Veterinary Colleges. Greenhill, LM, PD Nelson, and RG Elmore. J Vet Med Educ. 34(2): 74-78. 2007

Great post and interesting observations.

Tough but necessary topic. Thank you for opening discussion on this subject.

Pingback: I’ve been struggling with exactly what to say as I’ve watched the events of the last few days unfold. – Dr. Sam, Future DVM

Thank you, a necessary piece!

Thank you for posting.

How many non-white high schoolers are encouraged to engage in STEM? How many are encouraged to pursue STEM, a prerequisite for any science based profession in their undergrad studies? Could veterinarians reach out to schools to participate in career days or to offer internships at both high school and undergrad level.

The systemic failings occur way before the point in time of application to vet school – they start in pre-school and before.

Thank you for addressing this. I’ve never seen a black veterinarian in the USA, as a matter of fact.

So I’m incredibly disappointed by this post, to say the least, and it is all the more disheartening since it is coming from someone who helped me to think critically. I guess I’m one of those naive or disingenuous people who fail to see the evidence of “systemic racism”, but rather, byproducts of direct racism from the past and the evident economic disparities between the various groups. As a result of that past, many black people are living in neighborhoods that that limit their access to opportunities, that much is true. This influences ‘African American culture’, such as the stereotype that black people don’t like to swim…obviously this is not the case in Jamaica.

Well, it just so happens that there IS a lack of interest among black people and animal medicine. In my experience, black people not only tend to not be huge animal-loving people, they are actually AFRAID of animals. I am an anomaly in my family, not only being an animal person, but a bug lover as well, an anomaly as a female. Much of my family members were scared of animals and dogs specifically (until I demanded we get one). Many black people live in areas where the animals they are exposed to are ‘bully breeds’ that are used to intimidate people, barking behind fences. Why exactly do you not find this convincing? Why do you deny all the very valid reasons for these disparities between blacks and whites without a single bit of evidence? You’ve even provided evidence against systemic racism in this post, but denied it all the same. I’m sad for you that you are caving to this current destructive mentality our country is experiencing right now, to the point that you’ve deviated from your ‘evidence-only’ perspective to suggest that racism MUST exist whenever a ‘marginalized’ group is perceived to be disadvantaged in some way. That mentality is literally tearing us apart right now. Now I am alone not just as a multi animal-owning, bug loving black person, but alone is seeing this irrational movement for what it is.

It’s always interesting to see how people who admire one’s critical thinking and discourse when they agree with you see any disagreement as an indication of abandonment of principle or loss of intellectual integrity. You seem to feel your view of the issue is so self-evident that anyone who sees it differently is “caving” to social pressures. The idea that informed, critical-thinking people might genuinely see a subject differently and come to different conclusions that both have some legitimacy seems a very hard concept to entertain these days, especially in any domain perceived as political (which is just about everything right now).

Obviously, as a white person I’m in no position to debate your generalization about Black culture or attitudes. I would encourage you to consider the very different views of Dr. Greenhill in Navigating Diversity and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine, which discuss attitudes towards animals in a historical and cultural context. I don’t think there is any conflict between the idea that Black people may often have negative attitudes towards some animals and the idea that this is an expression of the effects of historical and contemporary racism built into the economic, political, and cultural systems of the U.S. In fact, I would consider the “byproducts of direct racism from the past and the evident economic disparities between the various groups” as a fair description of what systemic racism is–racism that relies not on bigoted attitudes of individuals but is intrinsic to institutions that have developed with discrimination against people of color built into them. You seem to think of racism as a feature of individual minds, but the term “systemic racism” is intended to reflect the fact that people of color are negatively impacted in many ways automatically by systems, not only by evil individuals with explicit racist attitudes.

In any case, I would encourage you to reflect on why, if you are truly an “anomaly” in your views, other people might see the issue differently. Are we merely ignorant or easily misled or naive? Do you really think this post reflects a shallow “hot take” on a popular topic, or is it possible that I have been engaged in trying to learn and think about race and U.S. history for many years and that my views, which you may legitimately take to be wrong, are at least the product of serious thought?

What seems to me to be “tearing us apart” in America now more than anything else is the inability for people to disagree substantively and respectfully and to engage with the content of each other’s ideas rather than dismissively categorizing each other as “us” and “them” based on our positions on hot button issues. Over and over in this comments, I see people laud or condemn me not based on the content of my arguments but on the degree to which they agree or disagree with that content. You condemn me for not providing “evidence,” and then you provide only your own personal experiences and feelings as proof that the whole concept of systemic racism is obviously mistaken. I’m not even sure that we disagree all that much, but the personalization of the discussion takes the focus off of the specific views and the evidence for them to the point that it’s hard to tell.

I’m happy to listen to your thoughts on the paucity of people of color in veterinary medicine and how we can address that, since presumably we share that goal at least.

I have posted here in the past as “GSmith9072” back when I believed in raw feeding and alternative medicine and was not thrilled with your posts, but eventually I did a 180 on my beliefs despite my personal anecdotes, dumped my colloidal silver down the drain and other unsupported remedies because of this blog. In fact, I came to this site yesterday to access your posts about the current evidence regarding raw feeding for my writing (off topic, I would appreciate a post on raw feeding for ferrets, as I was surprised to see that there is evidence for whole prey having a significant impact on their oral health). Your post about acupuncture and mention of the difference between “electroacupunture” and acupuncture of which there is no evidence for was integral in my decision to seek the best treatment for my 18 year old iguana which ultimately led to me avoiding putting her down against the recommendation of a vet for a year and counting.

I was arguing with my mom the other day over her choice to listen doctors who make extraordinary claims vs. the medical consensus (she feels the need to take supplemental vitamin D despite testing that she was at near toxic levels). I’m always trying to explain to her the difference between good and bad science, that real science has the capacity for change while people you should avoid listening to have fixed, religious-like beliefs. Therefore I am always trying to self-regulate my own biases and question even the sources I hold in high regard. It’s getting complicated and stressful since not even academic studies are equal and suffer from bias, which is why blogs like this are so important.

I’ve been reading and recommending your blog for years due to your consistent and unwavering adherence towards what the evidence is pointing towards. I have to say that it’s not just that I don’t agree, but that you’ve quite literally accused the veterinary community of concealing some level of insidious racism with no evidence.

I think we mostly agree, but disagree on this important aspect: that these issues are stemming from current systemic racism vs. past systemic racism. Furthermore, there are strong cultural and economic reasons for why black people are less interested in veterinary medicine and it is the ‘fault’ of no living person. I’ve thought about why I might see things differently at length.

Probably the most disturbing trend I’ve been witnessing and is responsible for the irritated tone you detected in my post is that non-black people are being heavily pressured into accepting every aspect of the narrative being forced right now, that there is evident racism in the “system” and that questioning this in the slightest or asking for evidence is just indicative of your “privilege”, bigotry, or racial prejudice. Even “white silence” is considered racist now and there is an effort being made to end the employment of offenders. I know your heart is in the right place on this topic as usual but I am alarmed that due to this idea that systemic or institutionalized racism cannot really be proven, it must be presumed to be there and doing otherwise is disingenuous and naive. Sadly, this view (that assumed racism is just racism) is also being internalized by black people, and, while I don’t have direct evidence, I suspect this will lead to more frustration, more anti-authority behavior, and ultimately, even MORE death by police officers who’ve also internalized the hatred leveled against them. Keeping in mind this current strife is based off of a unique incident that is not common in any way (ironically, people tend to get more outraged over something that is less common).

I provided anecdotal evidence for black people actually having less of a desire to work in veterinary careers because overall, much of them don’t like animals or are even afraid of them (dogs specifically), along with the economic disparities, as I mistakenly believed this was common knowledge (also, to provide more possible variables to defeat the idea that racism must be assumed). But I realize I should look for formal evidence.

I found in one of your references “Minority Student Perceptions of the Veterinary Profession: Factors Influencing Choices of Health Careers”, that some of the reasons listed coincide with my predictions: “economic disparities” “Little or no positive animal experience” “non-supportive environments”.

“The Attitudes of Minority Junior High and High School Students toward Veterinary Medicine” suggests minorities have a lack of interest in veterinary medicine and do not associate it with a satisfying lifestyle. That matches my experiences. I’d predict that black people would be more likely to view being a human doctor as a ‘successful career’. I found out on the AAMC website that the percentage of black people in human medicine vs. veterinary is twice as high (5%).

In Navigating Diversity and Inclusion in Veterinary Medicine, the chapter “A Historical Picture of Diversity in Veterinary Medicine” describes the valiant efforts of veterinary medicine to include more diversity, albeit it wasn’t as successful as desired. I also found from there:

“Caucasian/White students tend to better understand what veterinarians do, compared to African American/ Black and Hispanic/Latino students; and (3) African American/Black students had the fewest experiences with animals, the least positive image of veterinary work, liked animals the least, and were the least likely to be inter- ested in a career in veterinary medicine.”

So I see a consistent and honorable effort to recruit minorities that is just not really succeeding and some of my observations have validity. I know that my interest in science and animals/bugs contributed to making me an outcast growing up who would often get ‘stared at’ and slightly bullied by black/urban classmates. I also notice a sad tendency of some ‘urban’ black people who do choose to get pets, it tends to be for a ‘tough’ persona over companionship and interest. For instance, aggressive pit bulls (this was extremely common in the most popular rap/hip hop videos when I was watching them) or getting large snakes and cruelly feeding live animals.

Delving more into this for evidence of less animal interest, less black people seem to be into animal rights (I am anti-animal rights, but this is a different topic).

From “Attitudes toward animals among African American women in Los Angeles”

“The small number of prior studies of attitudes toward animals among African-Americans, and research on African-American attitudes toward the environment more generally, suggest that their views are slightly more anthropocentric and espe-cially utilitarian than those of whites (see Kellert and Berry 1980). However there is substantial evidence that these attitudes reflect socio-economic and cultural factors..”

Journal of Animal Law

“There is anecdotal reason to believe that many people of color – in particular, African Americans – view animals rights as a “white” phenomenon. ”

Another interesting article “The Johnsons Got A Dog On ‘black-ish’ Despite Dre’s Claim That “Real” Black People Don’t Have Them”

“According to a 2008 study at the University of Louisville, compared to white people, working class black people were more likely to be afraid of dogs, though there reportedly have been very few studies into the subject.”

And according to Pew Research Center, minorities own less pets. And finally, from “The People Who Are Scared of Dogs”:

“But sociologist Elijah Anderson did find some evidence of racial differences, at least among working-class whites and blacks. In his book Streetwise, about a diverse urban neighborhood in Philadelphia, he noticed that “many working-class blacks are easily intimidated by strange dogs, either on or off the leash.” He found that “as a general rule, when blacks encounter whites with dogs in tow, they tense up and give them a wide berth, watching them closely.””

“When we spoke, Chapman offered two possible reasons. First, many dogs in low-income urban areas are trained to be what he calls “you-better-stay-away-from-our-property” guards.”

This is consistent with my observation that pet ownership seems less common among black people. I think there’s more than enough variables to consider, besides some level of inherent current racism, although past racism is definitely a piece of this puzzle, if not the major player.

Thank you for addressing this issue.

I recently got rejected for a vet school. I am an immigrant from an East Asian country and grew up in a city. I feel the veterinary profession extremely unwelcome to applicants like myself. Applicants who grew up in animal farms are more likely to get accepted, and majority of the animal farms are owned and run by Whites.

Also, I don’t get financial support from my family and have to financially sustain my life while keeping my GPA competitive. However, owning a pet is one of the indices the committee look at to measure the companion animal husbandry and handling skills of applicants. If I barely sustain my life, how can I afford a pet considering the cost of pet food, accessories, and vet bills?

Veterinarians are dominantly Whites. An applicant is required to shadow a vet in order to name the vet as his/her referee. For applicants whose language is not English, accent and language fluency make the applicants susceptible to discrimination and prejudice. The vets simply avoid conversations and interactions with non-anglophone applicants. This will be difficult for us to build a positive relationship with the vets for a good reference.

All those experiences discourage me from pursuing my dream to be a vet. I have failed three times even though my GPA is exceptional. Now I regret that I didn’t choose medicine or pharmacy to be my career. If I could redo my life, I would never choose veterinary medicine.

I left a long reply but it’s not showing up and it wouldn’t let me post again. I assumed it was in a queue waiting for approval. Just wanted to make sure it’s visible somewhere.

I have posted here in the past as “GSmith9072” back when I believed in raw feeding and alternative medicine and was not thrilled with your posts, but eventually I did a 180 on my beliefs despite my personal anecdotes, dumped my colloidal silver down the drain and other unsupported remedies because of this blog. In fact, I came to this site yesterday to access your posts about the current evidence regarding raw feeding for my writing (off topic, I would appreciate a post on raw feeding for ferrets, as I was surprised to see that there is evidence for whole prey having a significant impact on their oral health). Your post about acupuncture and mention of the difference between “electroacupunture” and acupuncture of which there is no evidence for was integral in my decision to seek the best treatment for my 18 year old iguana which ultimately led to me avoiding putting her down against the recommendation of a vet for a year and counting.

Sorry, it got tagged as spam probably due to length. I posted it.

Great story, relevant and necessary. My concern is that your first two graphics (pie graphs on demographics of applicants vs. admitted DVM students) are confusing due to errors in the images. The first graphic adds up to 110% instead of 100%. The second does add up to 100%. I would hate for your message to not get across because of inaccuracies in the graphics, but it does make it hard for a reader to follow your argument from the get-go when the graphics don’t match what you are trying to explain. It looks like this came from the AAVMC data file you referenced. If you rectified this it would strengthen your message.

Thanks for pointing this out. Unfortunately, the page comes directly from the AAVMC report, and I don’t have access to the original data, so. I don’t know where the error occurred, nor can I fix it. I suspect the error doesn’t undermine the general point, but it would be better if the AAVMC could provide a correct figure.

Pingback: White Privilege – Be Your Own Vet