The goal of longevity therapies is to prolong both lifespan (the number of years an individual lives) and healthspan (the number of years free of significant disease or disability). Current preventative medical interventions, such as vaccines, have greatly increased lifespan, mostly by preventing death early in life. Medical treatment of age-related diseases also prolongs lifespan by delaying death, and it can increase healthspan somewhat by reducing the negative impact of disease on quality of life.

Unfortuntely, increases in lifespan driven by reduction of early-life mortality have exceeded increases in healthspan, and the period of disability and diminished quality of life preceding death has grown. This is clear for humans and appears true for dogs as well.

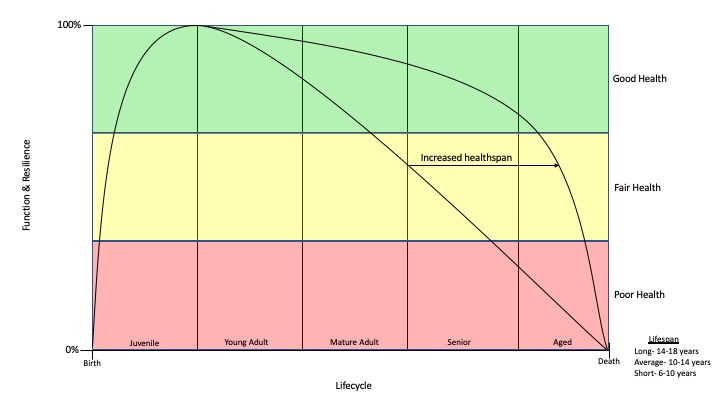

The length of life for dogs varies with breed, size, neuter status, and other variables. Lifespan ranges from an average of 6-10 years for the shortest-lived breeds up to 14-18 years for longer-lived dogs.

Regardless of the number of years lived, all dogs progress through a lifecycle that involves changes in physiologic resilience and functional capacity over time (see figure above). There is a rapid increase in function and ability to cope with external stressors from birth to physical maturity. The inevitable decline in health and function from this point can occur along variable trajectories.

The purpose of interventions to promote healthy aging is not only to increase the number of years lived but to maximize the period of good health and confine the loss of resilience and functional capacity to the shortest possible period. Therapies which delay death but do not prolong healthspan can reduce overall quality of life by prolonging the period of disability preceding death. Learning to quantify the impact of aging on health will enable us to better assess the impact of interventions on both lifespan and healthspan and achieve the greatest benefits for our dogs.

References

Lewis TW, Wiles BM, Llewellyn-Zaidi AM, Evans KM, O’Neill DG. Longevity and mortality in Kennel Club registered dog breeds in the UK in 2014. Canine Genet Epidemiol. 2018;5(1). doi:10.1186/s40575-018-0066-8

Michell AR. Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with-sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease. Vet Rec. 1999;145(22):625-629. doi:10.1136/vr.145.22.625

O’Neill DG, Church DB, McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC. Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England. Vet J. 2013;198(3):638-643. doi:10.1016/J.TVJL.2013.09.020

Adams VJ, Evans KM, Sampson J, Wood JLN. Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51(10):512-524. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00974.x

Great points! I wish they would consider these things on the human side, rather than letting our seniors live the life of a potted plant.