Screening

One of the topics I have written about frequently here is screening—testing apparently healthy individuals to look for disease that hasn’t yet cause clinical symptoms. Screening is popular in human and veterinary medicine because of the widespread belief that the earlier we detect disease, the more effectively we can treat it, and that a proactive approach is better for patients than waiting for diseases to show up with symptoms. Sometimes this is true. And sometimes it isn’t.

Screening is a complicated subject because it is often hard to know in general whether or not we are really benefitting patients, and it is nearly impossible to know for sure whether screening has helped or harmed any specific individual.

There are some situations in which it is pretty obvious that screening would be of no benefit-

- When the test is wrong and the patient doesn’t actually have the disease it says they have (a false positive result or misdiagnosis)

- When the disease is there, but it is not progressive and will never cause any symptoms or illness (overdiagnosis)

- When we don’t have any effective treatments, so knowing that a disease exists before symptoms appear just gives us more time to worry but no way to help the patient

The problem is that we often don’t know if a patient is misdiagnosed or overdiagnosed. Sometimes, an initial test is positive and follow-up testing shows they didn’t have the disease after all. But we don’t always get to do this testing, and we may treat patients, or even euthanize them, without discovering that our first test was wrong. And once we find a disease and treat it, we have no way to know if it was ever going to make the patient sick, so we usually assume we’ve helped the patient even when we haven’t.

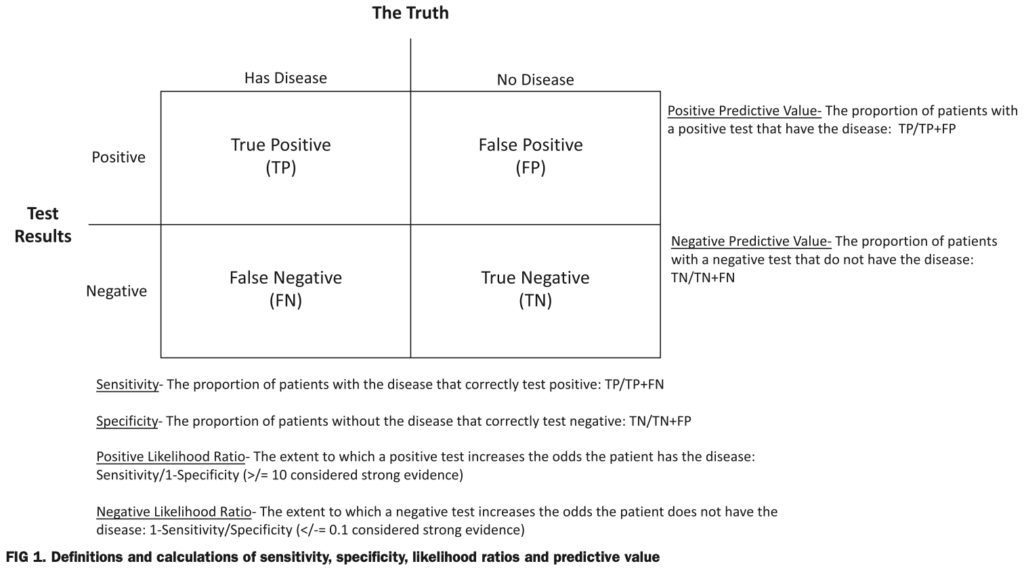

We can often determine how likely misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are in general by looking at statistics for groups of patients. (here’s a paper I wrote with more details about how this works) However, even this is sometimes difficult in veterinary medicine, where we don’t always have the information we need. This figure shows some of the important measures of how useful a test might be.

We can usually determine the sensitivity (how many of patients who have the disease correctly test positive for it) and specificity (how many patients without the disease correctly test negative for it) of a test by applying it to patients we already know have, or don’t have, the disease we are testing for. This is usually done when new tests are developed.

However, these values are not as useful as they seem in the real world. What we really want to know is the predictive value of a test. This is how many of the patients who test positive or negative actually have, or don’t have, the disease. This depends on how common the disease is in the group of patients we test.

If, for example, only 1% of dogs have a certain cancer and I test 100 dogs with a test that is 95% sensitive and 95% specific (pretty good numbers), only 16 of the dogs who test positive will actually have the disease. That means that 84% of the positive tests are wrong! You can imagine the potential harm we could do if we mistakenly told 84% of our patients they had cancer when they didn’t!

When a disease is rare, then negative tests are pretty likely to be true (99.95% in the example I just gave), but positive tests aren’t. Conversely, with common diseases, positive tests are a lot more likely to be right. Unfortunately, we don’t always know how common a disease is in the general population, so it can be hard to know how much to trust our test results.

So despite the fact that a lot of vets recommend very frequent and comprehensive testing, especially in older animals, we have to be careful about both when we do this and also how we use the results. An example I was asked about recently is the cancer screening test NuQ

NuQ

I have written about another cancer screening test, OncoK9, several times (1,2). This test was announced to much fanfare, and I was initially quite skeptical about its value. The company, to its credit, did pursue ongoing testing to improve the evidence base, and I did come to believe the test might be useful as an aid in diagnosis of suspected cancer, though I still felt we never had adequate evidence to recommend routine screening of health animals, as the manufacturer suggested. However, the company producing this test went out of business, and it is no longer available.

NuQ is another purported cancer screening test which is getting more attention recently, so I wanted to take a look at the evidence behind it. A paper published in 2022 reported the basic data, including the sensitivity and specificity of this test overall and for a few specific cancers. In general, the manufacturer reports a sensitivity of about 50% overall, and a specificity of 97%. The sensitivity is a bit higher for some cancers (e.g. 81% for hemangiosarcoma), and lower for others (e.g. 19% for mast cell tumors). This, of course, represents the numbers generated when testing dogs who are already know to have or not have cancer, and the values might well be different in another population based on age, breed, and other factors.

To figure out the predictive value of the test, we need to know the prevalence of cancer in the population we are testing. We seldom have this data, but a couple of papers have given us a general range of estimates we can use. A study earlier this year found cancer in about 3%-6% of apparently healthy dogs tested, and this is sufficiently in line with previous estimates as to be a reasonable ballpark.

Using these numbers, the overall positive predictive value of NuQ for cancer ranges from 34%-51.5% and the negative predictive value ranges from 96.8%-98.4%. Another way of thinking about this, is that of the apparently health dogs who test positive, as many as 75% of them might not actually have cancer (even with the higher 6% prevalence, 49% of them will falsely test positive for cancer).

If we look at the best-case performance of the test, such as with hemangiosarcoma, assuming. Prevalence of 6% and a sensitivity of 81.8%, the positive predictive value is still only 63.5%. That means we will tell about 64% of the owners whose dogs have a positive test that they have a cancer we can do little to treat, and we will give this grim diagnosis falsely to about 37% of these owners.

Of course, presumably vets will follow up on these results with imaging or other tests rather than treating or euthanizing patients on this basis alone. But this still means a significant cost for owners and, potentially, invasive tests that can cause pain or injury, when the chances of finding cancer are low. And for owners who cannot afford such testing, or treatment for cancer, we have given them terrible news they can do nothing about even if it’s true. Determining whether or not this is a good idea for a given patient is something that requires some careful thought and extensive, clear discussions with owners.

It is also important to remember that for most cancers we have no idea if earlier detection leads to longer, healthier lives for patients or not. It might, but this hasn’t always been true for human cancer patients, and it is quite possible we could harm more patients than we help by treating cancers that would never have caused illness or death. And there are some cancers for which we have no meaningfully effective treatments at all, so diagnosing these earlier is clearly not going to improve quality or length of life in these patients.

In general, I think vets and pet owners are entirely too optimistic about the value of screening given both how little evidence we have to show it helps in veterinary patients and the numerous examples of how it can cause harm in human medicine. For NuQ in particular, I find it difficult to picture many situations in which the likely benefits of running the test outweigh the uncertainties or potential harms.

Perhaps in a population at high risk of a treatable form of cancer, on age and breed or family history, we might get a useful early warning, but even then it isn’t yet clear that earlier diagnosis and treatment will make a meaningful difference. Certainly, routine screening of all healthy senior dogs does not seem justified based on the information we have now.

noticed lots of veterinarians were doing Fecal Dx antigen testing now rather than annual or semiannual float test. The company does advertise its sensitivity but not specificity (how many patients without the disease correctly test negative for it)

I am totally schocked at the significant posibility of a false positive of this test. I was recommended this test for my dog with an unspecified growth on spleen as seen on ekg. The test came out 100% positive. So i was given basically no chance for a long term survival of my dog. Did splenectomy just to extend its life by few months (maybe) only to find out from biopsy after surgery that the tumor was benign.

This is a situation in which this test is most reasonable to help guide decision-making, but it is crucial that the limitations of the results be understood.

Most splenic masses detected incidentally (as opposed to those that are actively bleeding) turn out not to be cancerous (e.g. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6805028/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27172343/), so this needs to be factored into the interpretation of such a test before we make a treatment decision.

Splenectomy may still have been an appropriate choice, but what you chose to do, and the emotional rollercoaster of the situation, could be quite different if the limitations of the test were discussed more clearly. Glad the end result was good news for your dog, though!!

I’m having a little trouble fully understanding the statistics but it looks like “positive = might have it, might not” but what about negative results for tests with numbers like this? If I can say “the test was negative which means that there is a 97% (or whatever) chance that your middle aged golden retriever does not have cancer”, that might be kinda nice for peace of mind. I see a fair number of goldens and sometimes their owners would like some reassurance that their dog doesn’t have cancer….which I can’t give at the moment.

All good questions!

The key part is the section of predictive value, which means the proportion of dogs who test positive what have cancer or who test negative and don’t have cancer. This varies with how common cancer is in the population we are testing, so there are always some assumptions made. For NuQ, making these basic assumptions, the chances of a dog who tests positive having cancer is somewhere between 35-50% (a bit better, about 63%, for hemangiosarcoma). A coin toss, essentially.

For a dog who tests negative, and has no other signs f cancer, you are right that it is a lot more reliable-about 97-98%. Of course, that only applies at that exact moment. It doesn’t mean they won’t have cancer in a month, 6 months, a year, etc.

I have had dogs with pretty compelling signs of cancer (including ultrasound findings) who tested negative, so even with such good numbers, it can be frustrating if the various test we use don’t agree.

The other thing to consider is how you are going to use this. if you are testing a lot of dogs regularly, then even if the % of mistaken results is small, the absolute number of dogs who get the wrong answer is still a problem. If you reassure 98 people who had no reason to worry in the first place (because we’re just screening apparently healthy dog) and scare the crap out of 2-3 people who also had no reason to worry, does the reassurance outweigh the fright (and the cost of the inevitable followup tests to confirm the blood test was wrong)? And what happens if some of those you reassure get cancer in the next year anyway. There’s no objectively right answer, but in my mind I don’t feel like this is a great way to use a test, and I worry about he effectively on owners from both false alarms and the feeling of reassurance followed by an actual cancer diagnosis.

I have a healthy 4 year old golden retriever that I electively have done this test on twice now – 1 month a part – both times he was fasted for 8-10 hours before. The first score was 50.5, the second was 60. I have electively done an extensive physical exam, regular bloodwork, US’s of internal organs, x-rays of chest and abdomen and an echo of the heart – all elective and at my request – all came back completely normal. My 6 year old golden (unrelated biologically to this one) just passed away from Hemangiosarcoma – heart – and showed zero signs or symptoms prior to his sudden death so I am obviously super paranoid now – his death has been the most traumatic and devastating of any pet loss I’ve ever experienced because I had absolutely no idea. For me the Nu.Q test has only added to my stress level now being in the gray zone and increasing in score. Any suggestions? I’ve heard they are now adjusting the score readings as I’m guessing they’re learning continually about these results the more dogs are being tested and I’m trying to keep in mind it is still relatively new.

Example of a false positive and the negative effects- Back in 6/23, my dog had the NuQ test done. It came back as moderate cancer risk. We did ultrasounds, x rays, infectious disease panels, blood work and enough small things were found to be worried, but no definitive cancer. I did another test weeks later and this time it came back as more than double the first, now high risk for cancer. We did a whole body CT scan and no cancer.

11/23 we did a different cancer screening test, that also came back high risk. Ultrasound showed a liver nodule, that was needle biopsied and came back as either benign or primary liver cancer. I decided to monitor with ultrasound and it shrank, then completely disappeared by 9/24.

The dog in question is still healthy and active 2 years later.

It’s a tough call but factor in the stress to yourself, the dog going thru all the testing that may be unnecessary, plus the cost. For me it was over $10k for the unneccessary testing.