What Is It?

Though I haven’t devoted a single post to the subject, I have mentioned Reiki many times and explained why it is one of the clearest examples of pseudoscientific nonsense out there. Believing Reiki has therapeutic benefits requires abandoning science and believing in magical “energy” that cannot be measured or evaluated in any way except the subject perceptions of practitioners with special abilities. In other words, magic.

Reiki is a variety of “energy medicine,” and there are many other forms of this, which differ in the theoretical explanations for their actions and in the degree of connection to particular religious traditions, including various styles of Christian faith healing, healing touch, therapeutic touch, Qigong, Tellington Touch, and others.

Reiki was invented (or discovered, depending on your point of view) by a Japanese monk named Mikao Usui in the early 20th century. Supposedly, he had been looking for a form of spiritual healing and had a vision during a long period of solitary meditation and fasting that led to his development of Reiki. Subsequent Reiki Masters have modified and develop the technique as well as spreading it to other countries.1–3

Does It Work?

Like all vitalist treatments, the underlying principles of Reiki cannot be scientifically validated and so must be taken on faith. The notion that nonphysical forces which cannot be seen or scientifically studied can nevertheless be intuitively sensed and manipulated with significant impact on physical diseases is scientifically implausible.

Despite the inherent difficulty in studying a therapy based on undetectable forces, many clinical trials have been conducted on Reiki, and many more on other similar types of energy medicine. Most are methodologically flawed and subject to placebo effects and other forms of bias and error. No convincing research evidence has emerged that Reiki, therapeutic touch, or other similar practices have any objective or significant impact on physical disease in humans or in veterinary species.4–9 Several studies have suggested that despite claims to the contrary, practitioners cannot reliably sense the presence of a patient or their “energy” when effectively blinded, which begs the question of how they can be channeling this mysterious force intentionally if they cannot detect it.10

Some studies do suggest, however, that the attention and human contact associated with Reiki and similar therapies is comforting to many human patients and can lead to improvement in subjective symptoms or the patients’ experience of their illness and their medical care. There is reason to believe that many domestic animals, including dogs and cats, may also experience comfort and positive physiologic responses to human contact, so Reiki may induce these responses regardless of the existence of any putative spiritual forces.11–18 This may have some mild clinical benefits, but it is unlikely to significantly affect the outcome of serious illness.

Reiki and Tooth Fairy Science

The most recent clinical study of Reiki for animals is a classic example of tooth fairy science– applying scientific methods to studying imaginary phenomena. The results are much more likely to be misleading than revealing.

Pacheco L. Marangoni M. de Oliveira Rodgrigues E. et al. Postoperative analgesic effects of Reiki therapy in bitches undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Cienc Rural. 2021;51(10):e20200511.

This study does a decent job of setting up a blinded, randomized trial using standard, validated measures for assessing pain. They also compared the practice to no treatment and to a placebo. Sounds good, but there is one pretty obvious choice that undermines this methodology– the placebo intervention.

Since Reiki involves touching, or passing hands closely over, the skin of the patient, one of the potential confounders is human contact. It is well-demonstrated that gentle contact and interaction with humans has calming effects on domesticated animals, lowering heart rate, blood pressure, stress levels, and potential behavioral signs of pain.

In this study, rather than having “real” Reiki as the test treatment and the same type of interaction without the channeling of mystical energy, the investigators used a rather bizarre placebo- “physical contact from gloves connected to 50-centimeter wooden rods applied by a non-Reiki therapist individual for the same length of time and method of application as the Reiki group.”

In other words, instead of standing close and gentle touching or almost touching the dogs, the investigators touched them with a rubber glove attached to a 1 ½ foot-long stick. Hmmmmm, I wonder if this awkward and unfamiliar behavior might have been less comforting, maybe even stress inducing, compared with normal petting, magical energy or no?

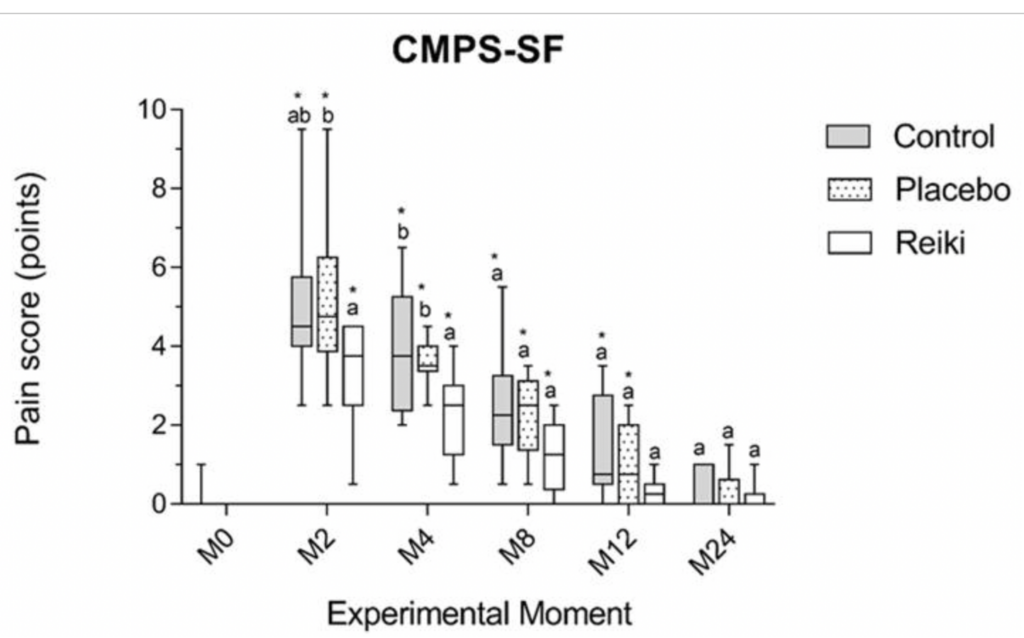

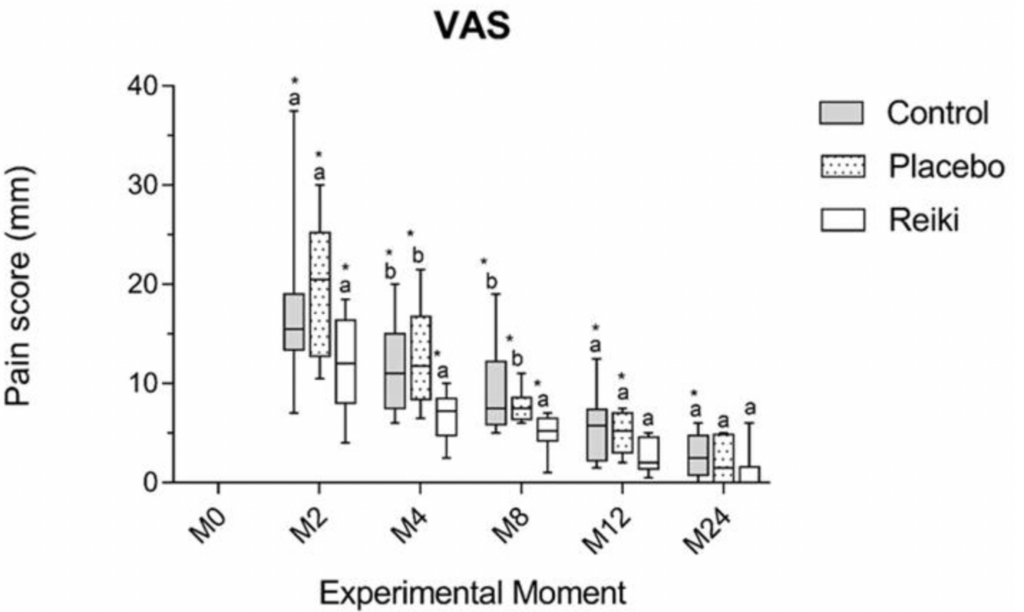

In any case, the results were not impressive. Comparing pain levels within each treatment at a series of time intervals after surgery, the only statistically significant differences in the first measure (Glasgow canine pain scale short form, CMPS-SF) were that pain scores were higher than before surgery at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours for the placebo and no-treatment groups, but only at 2, 4, and 8 hours for the Reiki group (Fig. 1). For the other measure (visual analog pain scale, VAS), the non-treatment group had higher pain levels at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours, the placebo group showed higher levels at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours, and the Reiki group had higher scores at 2, 4, and 8 hours after surgery (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. CMPS-SF scores

Comparing between the groups, the Reiki group had lower scores on the first scale (CMPS-SF) than the placebo group (but not the non-treatment group) at 2 hours and lower scores than both at 4 hours, with no other significant differences at 8, 12, and 24 hours (Fig. 1). On the second scale (VAS), the Reiki group had lower pain scores than the other two groups at 4 and 8 hours, but not at 2, 12, or 24 hours Fig .2).

Figure 2. VAS scores.

So, the apparent differences were only seen at a couple of time points and were not the same between the two measurement scales. Much more importantly, most of the scores were below the level usually considered high enough to warrant treatment (6/24 on the CMPS-SF and 35/100 on the VAS). So, dogs with mild pain already well-treated with conventional pain meds sometimes showed lower scores after Reiki, most mostly not. Not exactly a ringing validation.

At most, this might suggest that gentle petting has a mild comforting effect on dogs after surgery compared with no contact or with fake petting using a glove on a stick. There is no need to invoke undetectable magical energy fields. And there is certainly no reason to suggest that Reiki has a meaningful effect on pain with such small and inconsistent differences in dogs with already minimal discomfort.

(Interestingly, the placebo group actually showed higher scores than the no-treatment group at several of the early time points, especially on the VAS scale, and the Reiki group seemed to have lower scores than the placebo group but not lower than the non-treatment group at one point. Could this be because the weird fake petting was actually worse than no contact at all? The study wasn’t designs or the data analyzed to test this, but it’s an intriguing alternative possibility.)

Individual dogs were given additional pain medication if they had any score on either pain scale above the threshold for treatment (the investigators used 30/100 for the VAS score, while 35 is mentioned in the article they sit for this instrument. There is no consensus on the “right” cutoff for this tool.) About half the dogs in the placebo and no-treatment groups received this extra medication, and none of the dogs in the Reiki group did. That would seem to be a pretty dramatic difference!

However, this is not consistent with the much smaller and less consistent differences between the groups in pain scale results. Such a dramatic finding is suspicious for a failure to adequately blind the people making the assessment, though of course there is no way to evaluate this.

If such a difference is real, it would mean Reiki is a pretty powerful pain treatment. Given the implausibility of the premise behind the treatment, and the failure to find such dramatic effects in many other studies in other species, an error in the study seems a lot more likely. Such an unusual and dramatic finding would need to be replicated by independent researchers before it could be taken more seriously.

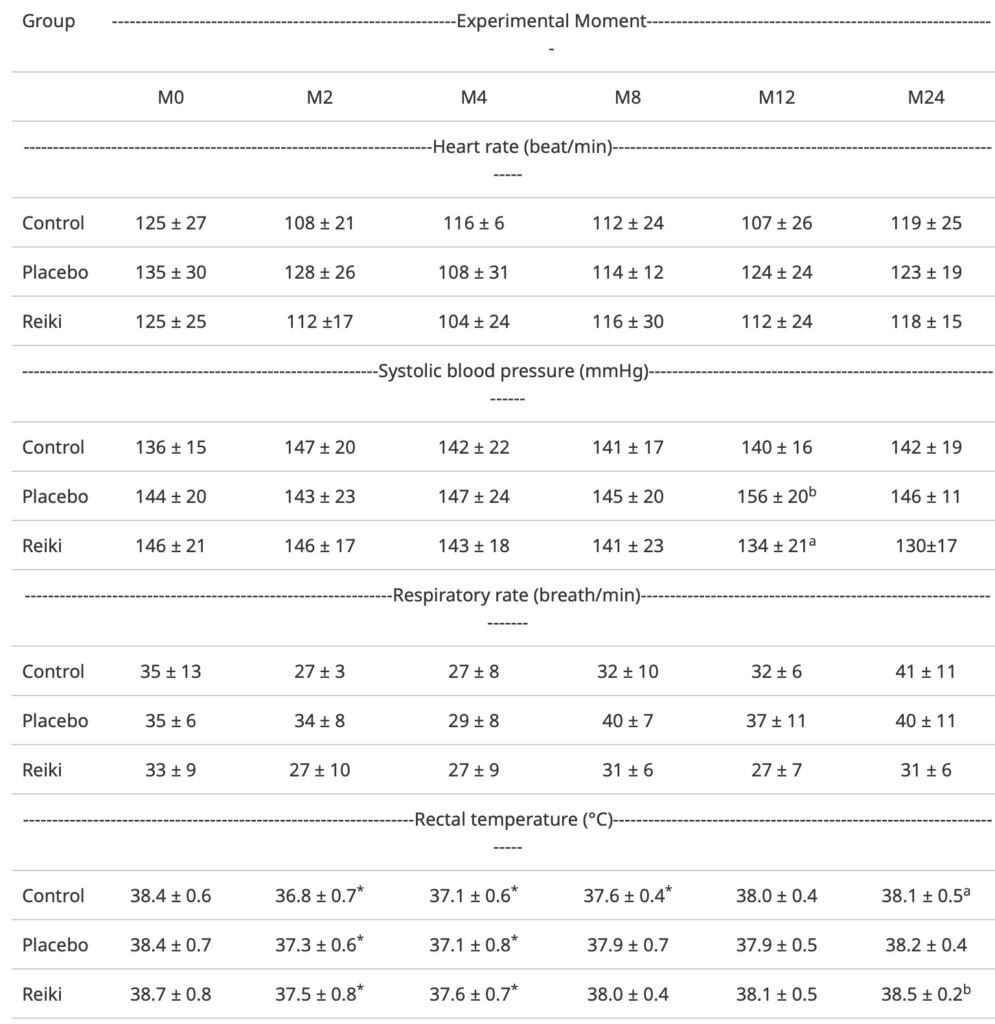

Almost none of the objective physiologic measurements different between the groups (Table 1), reinforcing the concern that bias may have affected the findings of more subjective pain measurements. This is actually a bit of a surprise since human contact has been previously shown to influence heart rate and blood pressure. Such inconsistencies weaken the argument that there is a clear and real pattern of effect here.

Table 1. Physiologic measurements.

Is It Safe?

No direct harm has been seen in studies of Reiki. The major risk of Reiki and other forms of energy healing is the delay or rejection of appropriate diagnosis and effective treatment that may occur if people mistakenly believe these therapies offer real hope of improving their pets’ condition.

Bottom Line

The idea that a magical energy force detectable only by specially trained people (who have been shown, in controlled studies, not to be able to detect this force after all) can have meaningful health benefits is highly implausible. Much of well-established scientific understanding would need to be totally wrong for this idea to be true. The evidence is generally poor quality, and consistent benefits have not been reliably demonstrated. Some non-specific effects from gentle, pleasant physical contact may be present, but we and our veterinary patients can enjoy that without the mystical nonsense and the false claims of important objective health effects.

Selected References

1. Singh S, Ernst E (Edzard). Trick or Treatment??: Alternative Medicine on Trial. London: Corgi; 2009. https://www.worldcat.org/title/trick-or-treatment-alternative-medicine-on-trial/oclc/788887954&referer=brief_results. Accessed November 10, 2018.

2. Carroll RT. The Skeptic’s Dictionary?: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. Wiley; 2003.

3. Rand WL. Reiki Master Manual?: Including Advanced Reiki Training. Vision Publications; 2003.

4. Robinson J, Biley FC, Dolk H. Therapeutic touch for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD006240. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006240.pub2

5. O’Mathúna DP. Therapeutic touch for healing acute wounds. In: O’Mathúna DP, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016:CD002766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002766.pub5

6. vanderVaart S, Gijsen VMGJ, de Wildt SN, Koren G. A Systematic Review of the Therapeutic Effects of Reiki. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(11):1157-1169. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0036

7. Lee MS, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Effects of Reiki in clinical practice: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(6):947-954. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01729.x

8. Ferraz GAR, Rodrigues MRK, Lima SAM, et al. Is Reiki or prayer effective in relieving pain during hospitalization for cesarean? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sao Paulo Med J. 2017;135(2):123-132. doi:10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0267031116

9. Joyce J, Herbison GP. Reiki for depression and anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD006833. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006833.pub2

10. Rosa L, Rosa E, Sarner L, Barrett S. A Close Look at Therapeutic Touch. JAMA. 1998;279(13):1005. doi:10.1001/jama.279.13.1005

11. Shahin M. The effects of positive human contact by tactile stimulation on dairy cows with different personalities. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2018;204:23-28. doi:10.1016/J.APPLANIM.2018.04.004

12. Beetz A, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Julius H, Kotrschal K. Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: the possible role of oxytocin. Front Psychol. 2012;3:234. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00234

13. Vormbrock JK, Grossberg JM. Cardiovascular effects of human-pet dog interactions. J Behav Med. 1988;11(5):509-517. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3236382. Accessed November 17, 2018.

14. Dudley ES, Schiml PA, Hennessy MB. Effects of repeated petting sessions on leukocyte counts, intestinal parasite prevalence, and plasma cortisol concentration of dogs housed in a county animal shelter. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;247(11):1289-1298. doi:10.2460/javma.247.11.1289

15. Mariti C, Carlone B, Protti M, Diverio S, Gazzano A. Effects of petting before a brief separation from the owner on dog behavior and physiology: A pilot study. J Vet Behav. 2018;27:41-46. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2018.07.003

16. Shiverdecker MD, Schiml PA, Hennessy MB. Human interaction moderates plasma cortisol and behavioral responses of dogs to shelter housing. Physiol Behav. 2013;109:75-79. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.12.002

17. HAMA H, YOGO M, MATSUYAMA Y. Effects of stroking horses on both humans’ and horses’ heart rate responses. Jpn Psychol Res. 1996;38(2):66-73. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5884.1996.tb00009.x

18. Lynch JJ, Fregin GF, Mackie JB, Monroe RR. Heart rate changes in the horse to human contact. Psychophysiology. 1974;11(4):472-478. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4852234. Accessed November 17, 2018.