I have written extensively about the positive and negative effects of neutering dogs for many years. This is an area of great controversy and rapidly advancing research. There is no simple relationship between neutering or age at neutering and health. Neutering itself changes many aspects of an animal’s physiology, and some of these changes have beneficial effects while others have harmful effects. The breed and genetic makeup of an animal, the age at which it is neutered, the environment in which it lives, and many other factors all work together to influence health, and the simplistic notion that neutering is “good” or “bad” for all dogs is simply untrue.

I recently found an interesting study examining the relationship between neutering and aggressive behavior in dogs which illustrates this complexity.

Farhoody P, Mallawaarachchi I, Tarwater PM, Serpell JA, Duffy DL, Zink C. Aggression toward Familiar People, Strangers, and Conspecifics in Gonadectomized and Intact Dogs. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:18.

It has traditionally been assumed, by dog owners and many veterinarians, that neutering reduces aggression, at least in males. The research to date, however, has been far from clear. Some studies support this idea, others show no effect of neutering on aggressive behavior, and some find neutering can increase aggression. The sex of the dog and the age at which it is neutered all play a role as well. While there likely is some relationship between neuter status and behavior, including aggression, behavior is a tremendously complex product of a multitude of factors, and what relationships there is between this and neutering is unlikely to be simple or universal.

This study approached the question in an interesting way. By looking through data collected in the past on thousands of animals using a behavioral questionnaire that has been widely used and is well-validated, they selected a huge population of dogs for which the details of neutering and also of aggressive behavior patterns were known. This has the advantage of a large enough s ample size to allow robust statistical comparisons. However, such a retrospective design has a lot of limitations, including the inability to acquire and consider relevant information that might not have been recorded in the survey and potential bias in the population of animals included. This was not a study population selected in an unbiased fashion specifically for the project but a database of voluntary responses to an online behavior questionnaire. People likely to fill out such a questionnaire, and their dogs, are likely different in meaningful ways from people not choosing to do so.

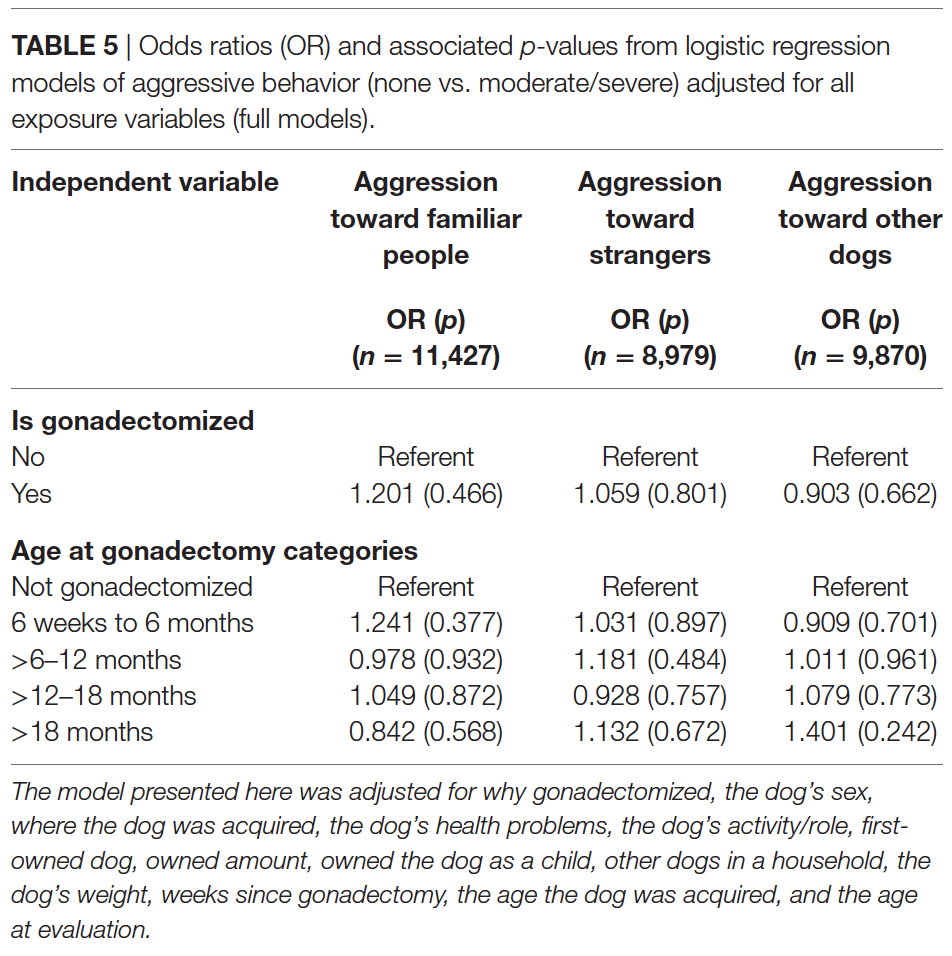

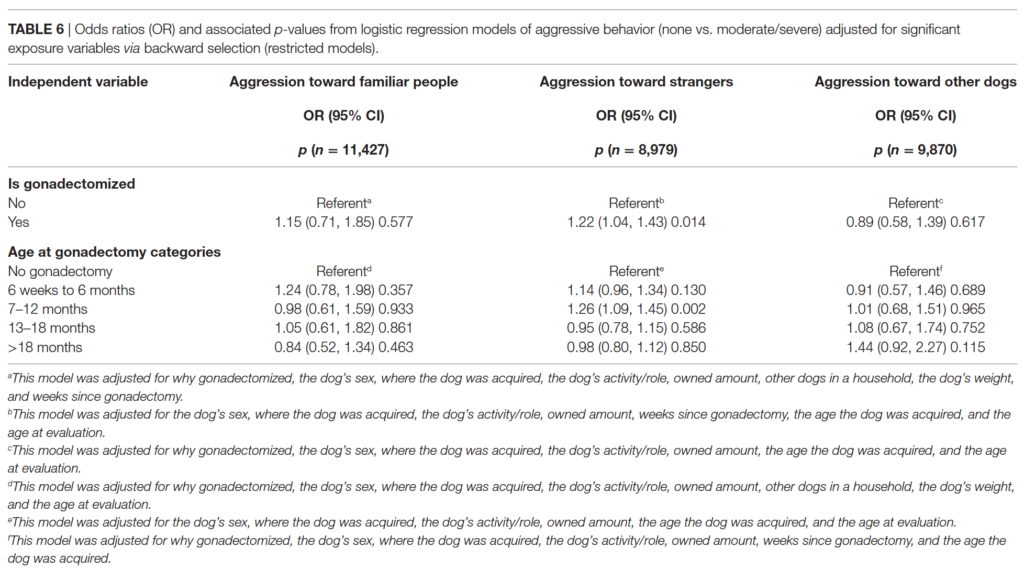

The researchers used mathematical techniques to compare the rates of different types of aggressive behavior (directed towards familiar people, directed towards unfamiliar people, and directed towards other dogs) with information about neutering and other factors (sex, age, weight, etc.). When all of the variables considered in the study were included in the model, no relationship was found between neutering at any age and any type of aggression.

When a different model was used to consider only a limited subset of the variables considered, the only relationship found was a small increase in the odds of aggression towards strangers among dogs neutered between 7 and 12 months of age.

The real-world significance of these findings is not completely clear. The authors emphasize that the results don’t support the assumption that neutering reduces aggression since neutered dogs were not significantly less aggressive than intact dogs. Of course, the other way to frame the findings is that the results suggest neutering has no effect on aggression either way, so aggressive behavior shouldn’t be a major consideration in decisions about neutering. The finding that aggression towards strangers was more common in dogs neutered between 7 and 12 months of age is likely a statistical fluke, and though the authors propose some possible hypotheses for it, they admit it is difficult to explain.

The study did not consider breed, which likely plays a significant role in some kinds of aggression based on previous studies. It also did not consider owner factors, which clearly influence both the behavior and the neuter status of dogs. It has always been an open question whether aggression by certain breeds or by intact dogs might have more to do with the owners who choose the breed and decide whether or not to neuter than with the neutering or breed per se. This study does not help clarify that question.

Overall, this is an interesting but not definitive contribution to the subject of how neutering might affect behavior. It undermines the traditional and simplistic notion that neutering prevents aggression, and it suggests that there are many factors influencing aggressive behavior in dogs and neutering is only one and likely not the most important.

“It is difficult to explain why our analysis demonstrated a significant increase in aggression toward strangers in dogs gonadectomized between 7 and 12 months of age. It is possible that this is a type I error or false-positive finding related to the use of two different models. It is also possible that the experience of gonadectomy at this age creates a long-lasting fear response to strangers—it is difficult to know. ”

I run a rescue so have had close contact with 100s of dogs that have been neutered in this age bracket. My subjective opinion, based on the anecdotal experience of the 100s of dogs in this age bracket that have passed through our care is this that 7-10 months is an age that many dogs seem to wobble psychologically and it’s plausible that robbing them of sex hormones at this formative age may not be best. Where possible, we wait until the dogs are over a year old and actually we now leave some nice male dogs entire – or at least endeavour to do so. People’s circumstances don’t always allow it.

I have a lab x in foster with me at the moment who is now 12 months. He’s quite full-on… bold in some ways and anxious in others. He is essentially dog-social but awkward in his body language and one senses that he could get himself in trouble if he got it wrong. I am very wary indeed of tipping him over the edge by neutering him at this time. We’re choosing instead to keep him safe in foster in a household of very savvy dogs that are teaching him the ropes in a proportionate way.

has there been any studies on how temporary castration effects aggression? I always “believed” castration often made fear/anxiety aggression worse but usually reduced male dominate aggression. https://nz.virbac.com/products/reproduction-and-contraception/suprelorin

Thank you as always for your informative posts.

When it comes to studies on aggression and behavior, one of the flaws that I see consistently is that there is no metric for judging the behavior and mostly it is based on the owner’s opinion.

I have a lot more dogs than most people, not as many as some, but I’ve yet to see a significant change in Behavior or personality after altering either male or female dogs. Not to say it cannot happen, but it’s just not something that I have seen so far, having owned over 30 dogs in my lifetime thus far. As a matter of fact I would say that so many of the things that people claim will change a dog’s personality just don’t seem to have an effect on any of the animals that I have owned in my entire life. Either I’m just very very lucky or people see what they want to see, probably including myself in that statement.

Another possibility at that 7-12 months age bracket is a fear period and a trip to the vet is often extremely scary and stressful. The effects of that threatening experience stay with them. Echoing what another commenter said, owner observations are not likely to be valid, and unless we can rule out a stressful experience during a period when that experience may make a strong mark on a dog, we can’t know for sure. (I’ve read the studies and choose late or no neutering.)