Back in January of 2023 I reviewed claims for a purported anti-aging supplement for dogs called Leap Years. My conclusion at the time was-

Leap Years is similar to most veterinary supplements on the market: It is based on some plausible ideas with limited supporting evidence, and it is marketed with claims that go well beyond anything scientifically proven or reasonable.

In that review, I pointed out that one piece of evidence the manufacturer cited to support their claims was an unpublished clinical study conducted at the veterinary school at North Carolina State University (NCSU). That study is still has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but the company has recently released a report on the preprint service Bioarxiv.

This is an increasingly common practice which is supposedly intended to make important information available more quickly, but which in most cases has more public relations value than scientific value. Until a paper is put through peer-review, it has only been critically evaluated by the authors or people they have chosen, which leaves lots of opportunity for bias. Such preprints may change significantly before publication or even never be peer-reviewed and published at all.

Preprints are clearly a lower level of evidence than full published research reports, but they do at least provide more detail for anyone interested in evaluating the research and claims made using it. As you have probably already guessed, that’s what I intend to do here!

The Study

The study was a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in accordance with appropriate methodological guidelines, which is always nice to see. The authors do a good job of describing the methods, including the bias-control practices, progress of subjects through the trial, and the potential limitations. The one critical piece of information missing is the actual chemical compounds used in the supplement.

As discussed in my previous review, Leap Years supposedly contains an NAD+ booster, which the company states is not NMN but otherwise does not identify. This was given daily for the duration of the 6-month study period. The supplement is also claimed to contain a senolytic, which is also not identified and which was given on two consecutive days each month during the study.

The FDA is pretty clear that veterinary supplements are not covered under the limited regulatory rules for human supplements (the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act or DSHEA). Anything marketed for animals must either be a food or a drug. Leap Years is clearly not a food, and the claims made for it very much sound like treatment claims for a veterinary drugs:

[Leap years] significantly improves owner-assessed cognitive function and may have broader effects on frailty, activity and happiness as reported by owners.

That would make it seem like the company is marketing an unlicensed veterinary drug without first demonstrating safety and efficacy, as is required. However, the FDA does not seem to have the resources or political backing to effectively enforce these rules, and the same is true for many other veterinary supplements. Legal or not, it seems to me unethical (if not unusual) to market a supplement with undisclosed ingredients and claim that it prevents or treats serious health problems in dogs. This study does nothing to address that concern.

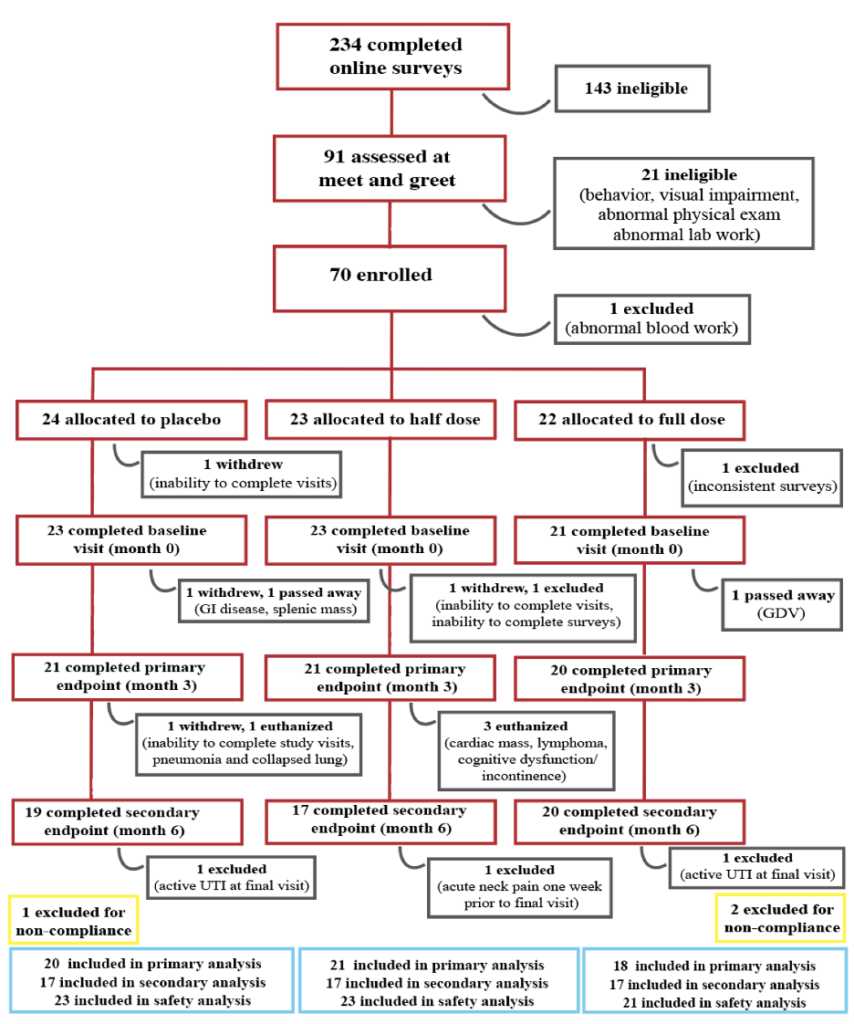

The trial started with 67 dogs randomized to placebo, low-dose supplement, and high-dose supplement (though the authors refer to these as “low-dose” and “full-dose,” which seems an obvious attempt to avoid the potential negative connotations and anxiety that might come with claiming to provide a “high” dose of whatever the undisclosed ingredients are). Subjects dropped out at various stages of the study for a variety of reasons. The total dropout rate was a bit high (19-26% from baseline to final analysis of the data), as is to be expected with an already old population. However, the dropouts seemed roughly balanced across groups, so while this might have affected the statistical power of the study, it probably didn’t bias the results for or against any of the treatments.

The dogs were included in the study if they were at least 10 years old and had mild or moderate cognitive dysfunction as assessed by a validated tool (CADES). They also had to be cooperative for behavioral testing and not so sick or debilitated that they couldn’t complete the various evaluations of the length of the study. All of these are reasonable inclusion criteria.

There were quite a few outcomes measured, though at least these were appropriately identified as a primary outcome (which is all that is supposed to matter when one critically evaluates a study like this) and secondary outcomes (which are supposed to be viewed as potentially interesting but not probative).

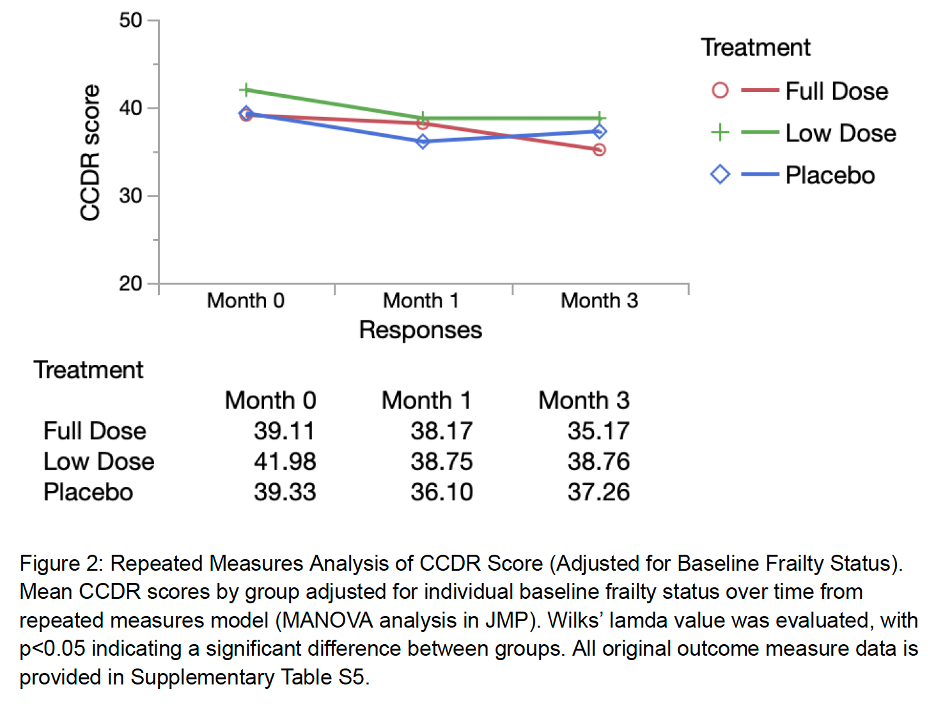

The primary outcome was the change at 3 months in a validated measure of canine cognitive dysfunction (CCDR, not the same as used to test dogs for inclusion in the study). As the figure below shows, all groups improved, including those taking a placebo, which is a classic finding for non-specific effects of participating in a clinical study. Patients tend to get better due, most likely, to the increased care, attention, and monitoring they get as study subjects, even if the treatment doesn’t do anything (which is part of why having a placebo group is so important).

At 3 months, the placebo group looks better than the low-dose group, and the high-dose group looks better than both, and the authors report, “There was a significant difference between treatment groups over the three-month period (p=0.02).” However, differences in “successes” and “failures” (improvement or worsening of CCDR scores) between groups were not significant at 3 months.

More importantly, it’s not clear if these differences would be meaningful in terms of function or quality of life even if they were statistically significant. It is not even clear that these differences are real since they are variable across time periods and do not show the expected relationship between dose and response (the placebo group should stay the same or get worse, the low-dose group should get a little better, and the full-dose group should improve more than the low-dose group).

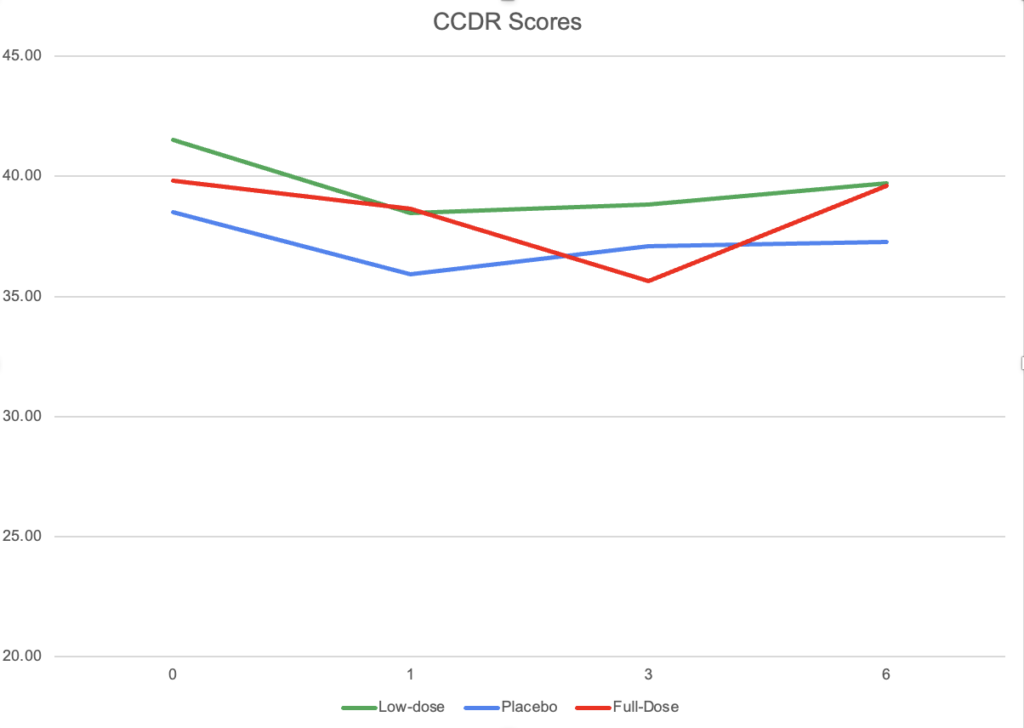

Expanding the chart to include the data from the 6-month timepoints (reported in the supplement to the preprint) shows the lack of these relationships and suggests that there is not clear and meaningful improvement with the supplement. Even though the 3-month timepoints was reported as a prespecified endpoint, it is interesting that it is the only timepoints that seems to show a significant improvement in a treated group and not the placebo group. Despite the statistical difference reported, it is pretty clear that the primary endpoint did not show the treatment to be effective.

The secondary outcomes also failed to show any clear evidence of a beneficial effect:

- The CCDR was measured again at 6 months, and there were not changes nor differences within or between the groups

- There was no change within groups nor differences between them in activity level determined by an objective monitoring device

- There were no significant differences between the groups in the number of dogs reported to have maintained the same level of activity. The results also don’t show the kind of progressive effect with increasing dose that would be expected if there was actually a real treatment effect:

placebo 55% unchanged

low dose 62% unchanged

high dose 44% unchanged

- Similarly, no significant differences or dose response was seen in the percentage of dogs reported to have increased their activity level:

placebo 20% increased

low dose 10% increased

high dose 39% increased

- There were no statistically significant differences or dose response seen in the proportion of dogs with stable or improved frailty scores:

placebo 55% stable or improved

low dose 76.2% stable or improved

high dose 72.2% stable or improved

- A variety of cognitive function tests were run on the study dogs. These haven’t been validated to show changes over time or drug treatment effects, though they could potentially be useful for doing so. There were no significant differences and no clear sign of a dose response for these tests.

- Cylinder test- all groups improved with no differences between them

- Detour test- there was a slight decline in the full-dose group, a slight improvement in the other groups, and none of these differences were significant

- Sustained gaze test- all groups improved with no differences between them

- Gait speed- there were no changes nor differences between groups

Only a limited subset of the results was reported for owner-reported happiness in the paper, and I have not dug through the full data spreadsheet to find the rest, but the most hopeful subset reported by the authors still does not show a clear effect. - At 6 months, there were some differences in the proportion of dogs reported to get better on this measure, but these were not statistically significant, and again they don’t show a logical dose response:

placebo 24% better

low dose 47% better

high dose 35% better - At 3 months, there were some differences in the proportion of dogs reported to get worse on this measure, but these were not statistically significant:

placebo 15% worse

low dose 10% worse

high dose 0% worse

The authors also monitored for adverse effects and classified these according to appropriate standards. There were few serious adverse effects observed, and these were evenly distributed between the groups and did not suggest any dramatic safety problems with the product.

Bottom Line

This report does not count as a peer-reviewed publication, and it adds only a little to the evidence already discussed a year ago to support the product claims. However, the report is useful in that it provides more detail about how the study was conducted and what the results were. Generally, the study was designed and reported appropriately, and the level of control, for bias was pretty good. Unfortunately for the company, the results failed to show statistically significant or clearly meaningful benefits for treated dogs.

The discussion and the company website, of course, try to present the findings in at least a slightly positive light, but the final statement that the product, “can be used safely to mitigate cognitive decline in senior dogs and might have broader effects on dog health manifesting as improved happiness and reduced frailty” is certainly not supported by the actual results reported here. The best we can say is that there were no apparent signs of significant risk and there were a few non-significant findings that might turn out to be mildly beneficial at a low but significant level in a larger study or with different outcome measures.

This level of evidence is never the definitive word for or against a treatment, but that this is the best the company can come up with after over a year on the market is not encouraging. The company makes claims which seem likely to be prohibited for a veterinary supplement, and they rely on anecdote and questionable extrapolation from theoretical science and results in other species to market the product, and the release of this study does nothing to strengthen their case.

March 12, 2024- Addendum

Today Dr. Nir Barzilai announced that Dr. Sinclair was resigning from the presidency of the Academy for Health and Lifespan Research. It is nice to see some consequences for such clear, commercially motivated misuse of science. Hopefully, this will encourage Dr. Sinclair to focus more on research and less on selling unproven supplements, for dogs or humans!

this study was all over the internet news this morning so i ask the chatbots about it.

Dr. Arthur Malernee

@artmalernee

what do you know about this study A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial Demonstrates Improved Cognitive Function in Senior Dogs Supplemented with a Senolytic and NAD+ Precursor Combination.

Katherine E Simon, Katharine Russell, Alejandra Mondino, Chin-Chieh Yang, Beth C Case, Zachary Anderson, Christine Whitley, Emily Griffith, Margaret E Gruen, Natasha J Olby

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.26.581616

This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review [what does this mean?].

00012707

AbstractInfo/HistoryMetrics Preview PDF

Abstract

Age-related decline in mobility and cognition are associated with cellular senescence and NAD+ depletion in dogs and people. A combination of a novel NAD+ precursor and senolytic, LY-D6/2 was examined in this randomized controlled trial. Seventy dogs were enrolled and allocated into placebo, low or full dose groups. Primary outcomes were change in cognitive impairment measured with the owner-reported Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating (CCDR) scale and change in activity measured with physical activity monitors. Fifty-nine dogs completed evaluations at the three-month primary endpoint, and 51 reached the six-month secondary endpoint. There was a significant difference in CCDR score across treatment groups from baseline to the primary endpoint (p=0.02) with the largest decrease in the full dose group. There were no significant differences between groups in changes in measured activity. However, the proportion of dogs that improved in frailty and owner-reported activity levels and happiness was higher in the full dose group than other groups. Adverse events occurred equally across groups. All groups showed improvement in cognition, frailty, and activity suggesting placebo effect and benefits of trial participation. We conclude that LY-D6/2 significantly improves owner-assessed cognitive function and may have broader effects on frailty, activity and happiness as reported by owners.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Grok

@grok

I am unable to access the full study as it is behind a paywall. However, from the abstract, it seems that this randomized controlled trial investigates the effects of a combination therapy of an NAD+ precursor and a senolytic compound called LY-D6/2 on cognitive function and activity levels in senior dogs. The primary outcomes measured were changes in cognitive impairment using the Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating (CCDR) scale and changes in activity using physical activity monitors.

The results of the study indicate that there was a significant difference in CCDR scores across treatment groups from baseline to the primary endpoint at three months. The full dose group showed the largest decrease in CCDR scores, suggesting an improvement in cognitive function. However, there were no significant differences in changes in measured activity levels between the groups.

Despite this, a higher proportion of dogs in the full dose group showed improvements in frailty, owner-reported activity levels, and happiness compared to the other groups. No significant differences in adverse events were observed between the groups. The study concludes that the combination therapy of an NAD+ precursor and senolytic LY-D6/2 significantly improves owner-assessed cognitive function in senior dogs and may have broader effects on frailty, activity, and happiness as reported by owners.

Dr. Arthur Malernee

@artmalernee

was the nnt and nnh part of the rct

Grok

@grok

In the context of the study “A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial Demonstrates Improved Cognitive Function in Senior Dogs Supplemented with a Senolytic and NAD+ Precursor Combination,” the terms “NNT” and “NNH” were not explicitly mentioned or discussed. These abbreviations typically refer to “Number Needed to Treat” and “Number Needed to Harm,” which are statistical measures used in clinical trials to determine the effectiveness and safety of an intervention.

However, the study did evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combined senolytic and NAD+ precursor therapy in improving cognitive function in senior dogs. The results showed significant improvement in cognitive function, as measured by the Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating (CCDR) scale, in the full dose group compared to the placebo and low dose groups. Additionally, the study found no significant differences in adverse events between the treatment groups, suggesting that the therapy was well-tolerated and safe.

In conclusion, while the NNT and NNH were not directly addressed in this study, the results suggest that the combination therapy of a senolytic and NAD+ precursor may be an effective and safe intervention for improving cognitive function in senior dogs.

our clients are going to be taking these dog supplements. Is dr ramey still alive? Im sure he will be amused but i suspect skeptvet is a little younger than he is.

Dr. Arthur Malernee

@artmalernee

http://skeptvet.com//2023/01/the-latest-in-veterinary-aging-supplements-leap-years-by-animal-biosciences/

Grok

@grok

In the article “The Latest in Veterinary Aging Supplements: Leap Years by Animal Biosciences,” the author, Dr. David Ramey, offers a critical perspective on the Leap Years supplement and its claims. The article highlights the lack of evidence for the supplement’s effectiveness and questions the credibility of the company’s claims.

Dr. Ramey points out that the study supporting the supplement’s effectiveness has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, and the only available information comes from a press release. He also notes that the study’s methodology and results are not fully disclosed, making it difficult to evaluate the supplement’s efficacy.

Furthermore, Dr. Ramey questions the credibility of the company’s claims, as they have not provided any evidence of their supplement’s effectiveness in peer-reviewed scientific journals. He also raises concerns about the potential harm that could result from using the supplement without proper evidence of its safety and efficacy.

In conclusion, the article “The Latest in Veterinary Aging Supplements: Leap Years by Animal Biosciences” provides a critical analysis of the Leap Years supplement and its claims. The author, Dr. David Ramey, emphasizes the importance of evidence-based medicine and urges caution when considering the use of supplements without proper scientific backing.

Another example of the uselessness of these AI tools at this point. The article is not behind a paywall, David was not the author of my blog post, and there are lots of other obvious factual errors.

Where are you seeing that the 3 month primary endpoint results were not statistically significant?

You state:

“While the placebo group looks better than the low-dose group, and the high-dose group looks better than both at 3 months, none of these differences were statistically significant.”

Yet that seems to be directly contradicted by the study’s Results section which says, “There was a significant difference between treatment groups over the three-month period (p=0.02), with the full dose group showing the largest decrease (improvement) in CCDR score.”

You’re correct the 6 month endpoint shows no significant difference but, as I’m reading it, the 3 month endpoint does seem to reach statistical significance.

Thank you for pointing this out. I was not clear in my explanation, so I have edited the section to be more precise.

The differences in success” or “failure” between groups based on CCDR score at 3 months was not statistically significant. The authors do report “a significant difference between treatment groups over the three-month period (p=0.02).” It’s not entirely clear what this means, though, given the figure and data provided. If we look at the data from baseline to 6 months, here are the numbers (averages from the spreadsheet provided in the appendix, which seem to differ slightly from the numbers given in the figure)-

41.52 38.48 38.81 39.72

38.50 35.91 37.10 37.26

39.82 38.67 35.65 39.60

Full-dose scores are higher than placebo at all points except at 3 months. All groups’ scores decreased in the first month, while the full-dose decreased more in the second month and then increased markedly in the subsequent months. If the analysis found a statistically significant difference at 3 months, then that would show that the low-dose group got a little worse while the full-dose group got a lot better and the placebo group was between the two. Not a very logical dose-response relationship, and difficult to interpret in a clinically meaningful way.

Furthermore, the next 3 months seemed to show that the placebo group stayed about the same, the low-dose group got a little worse, and the full-dose group got a lot worse. Also not logically interpretable if the drug is working, and it is puzzling that this difference wasn’t significant even though the increase in the full-dose group score was greater than the decrease between months 1 and 3. (would be great to see error bars for these data!)

The bottom line is that while a statistically significant difference was reported at one of the three time points measured, it doesn’t really support the claim that the supplement is working.

Its been 50 years since i took a statistics class so help me out here. The chatbots say they will run the math for me if i provide the following (below). Are you taking the authors word that they ran the math correctly or did the two of you going back and forth about significance run the math yourself from the data given?

In order to calculate the statistical significance of a randomized control group, I need the following data:

Sample size: The number of participants in the control group and the number of participants in the experimental group.

Data points: The measurements or observations from each participant in the control group and the experimental group.

Data type: The type of data collected (e.g., continuous, binary, ordinal, etc.) and whether it follows a normal distribution.

Effect size: The difference between the control group and the experimental group, which can be measured by the effect size (e.g., Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, or odds ratio).

Statistical significance level (alpha): The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true (usually set at 0.05 or 0.01).

Statistical test: The appropriate statistical test to compare the control group and the experimental group (e.g., t-test, ANOVA, chi-square test, etc.).

Please provide me with the necessary data, and I will help you calculate the statistical significance of your randomized control group.

I did not recheck the statistics, and I VERY MUCH doubt a chatbot can be relied on to do that correctly. The choice of the test, the normal/non-normal distribution of the data, and many other judgement calls need to be made, and a statistician should be relied on to make them. That is one reason why peer review is important and should always include a statistical review.

The raw data is available as supplemental files associated with the preprint on bioaRxiv, soy can use that if you want to do this.

Pingback: 5 Best Dog Longevity Supplements - Longevity Advice

Pingback: 14 Best Dog Longevity Products - Longevity Advice

For a randomized trial a SAP (statistical analysis plan) prior to registration of the trial is necessary. Without this it is challenging to evaluate the validity of the statistical analysis.

Dr. Arthur Malernee

@artmalernee

was a sap done on this trial? Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial Demonstrates Improved Cognitive Function in Senior Dogs Supplemented with a Senolytic and NAD+ Precursor Combination.

Grok

@grok

No, the information provided does not mention a SAP (Statistical Analysis Plan) being done on the randomized, controlled clinical trial that demonstrated improved cognitive function in senior dogs supplemented with a senolytic and NAD+ precursor combination.

@art william malernee

Were you able to do a proper recalculation?

I put my dog on Leap Years about 8 months ago. He, like others on Reddit, developed pancreatitis and kidney failure and died. His blood test just prior to starting this crap was normal.

Since this appears now to be a pattern, I am looking into the actual ingredients before more dogs die.

Were you able to do a proper recalculation?>> no