Obviously, the whole purpose of the SkeptVet is to combat misinformation and to promote evidence-based pet health. I first used the term Age of Endarkenment in a post for the much more influential Science-Based Medicine blog. Then, I was focused on the relatively narrow issue of the AVMA being unwilling to acknowledge the clearly evidence fact that homeopathy is useless pseudoscience and that vets shouldn’t offer it to clients (you can refresh yourself on the whole sorry saga in these posts).

When I was honored with the VIN Veritas Award, I was invited to give a rounds presentation on the Veterinary Information Network (unfortunately, you’ll need to be a member to view this). I used the opportunity to expand on the underlying cultural currents that have led to an apparent explosion in misinformation and mistrust of science, and to compare these to the principle soft the Age of Enlightenment, which underlie the achievements and progress science has brought to many fields, including healthcare.

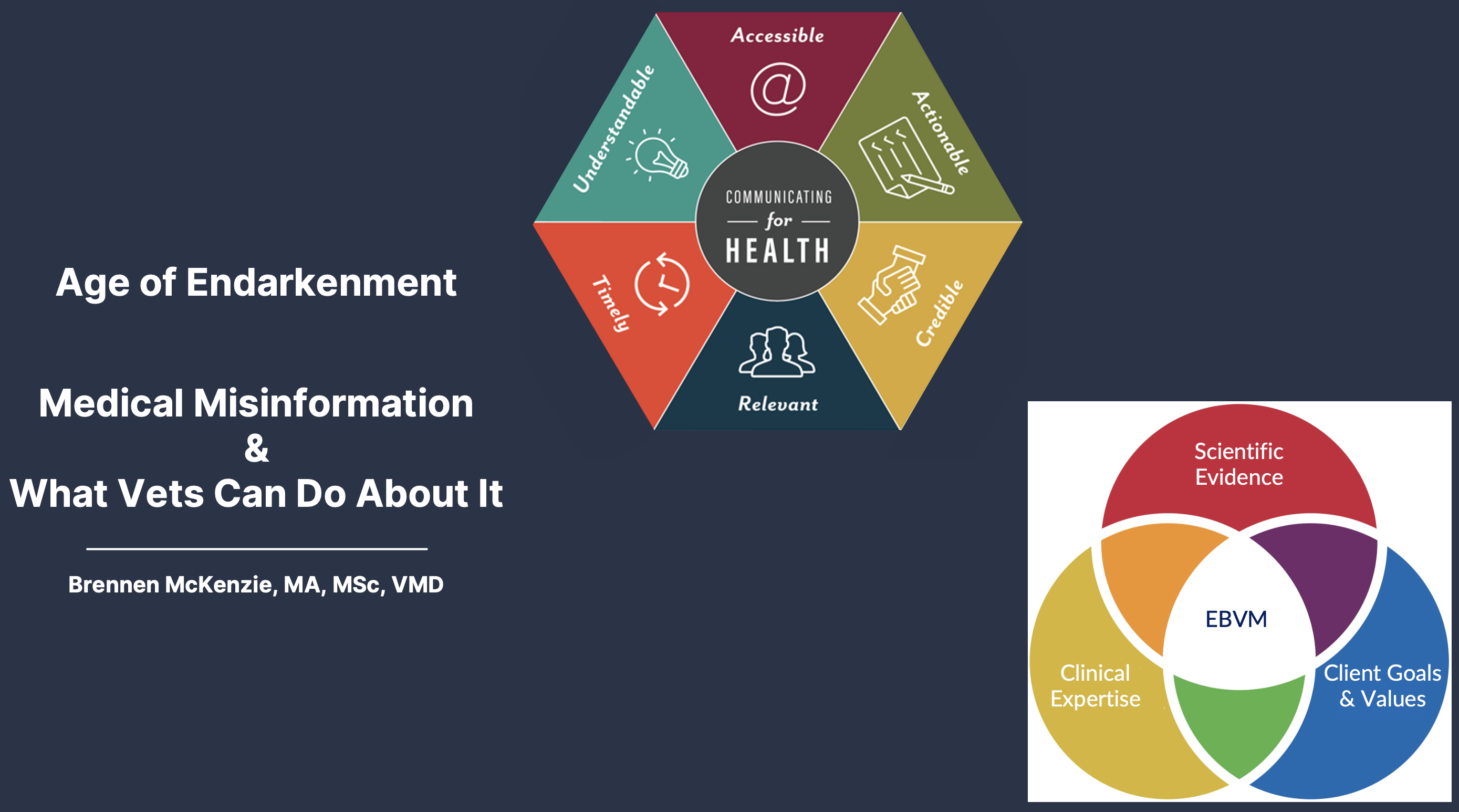

I have since given a shortened version of this talk at the Western Veterinary Conference, and I will be giving this again at PacVet in San Francisco next month. Here is the slide deck and a summary of the talk.

WHAT IS THE DISEASE?

Mistrust of science and science-based medicine, as well as misinformation, pseudoscience, and false beliefs around medical topics have been around as long as science as a method for understanding nature has been around. We are currently in a moment when these problems are growing and spreading, and this threatens the health and wellbeing of humans and animals.

Misinformation is, by definition, information that is incorrect, not true. This may be a claim that is completely incorrect – for example, the assertion that vaccines are the cause of autism in children – or it may be something that is partially correct or even wholly correct, but in some way is misleading. The notion that vaccines have side effects is perfectly correct, for example. The notion that those side effects are far greater than their benefits is not correct. Misinformation can have elements of truth in it.

How do we know what is true or not true in terms of medical information? Ideally, we base that decision on the best current scientific evidence. Science is the best method that we have for understanding what’s true about nature and what’s not. Unfortunately, we can’t all be experts in every area of science or even every area of medicine. We do, to some extent, have to rely on the consensus of people who are experts in that area. This is probably the most problematic issue because people are often skeptical of experts, and we don’t like to be told what to think. We like to have our intellectual independence, which is a good virtue but gets us into trouble when we think the 20 minutes on the internet makes us an expert in any and all topics.

To deal with misinformation, we have to accept the fundamental premise that there are things that are true and things that are false, that science is probably the best way to distinguish those, and that sometimes we have to rely on the consensus of experts in a field to tell us what the truth is when we aren’t able to necessarily make that judgment ourselves.

HOW BAD IS IT?

The good news is that most people actually do trust science. If you survey people around the world, there are pretty high levels of trust in the things that scientists say about the natural world. That is still the majority of people almost everywhere.

People in particular trust medical scientists, especially doctors, and nurses. There are high levels of confidence in what medical people say about health and disease. Even though there is sometimes a worrisome degree of mistrust, we shouldn’t forget that the majority still think that scientists and medical scientists know what they’re doing and are on their side. This applies to veterinarians and veterinary technicians and nurses as well.

Unfortunately, mistrust and misunderstanding of science is still quite common. Here are some survey findings that should be very disturbing:

- 36% of people only believe in scientific claims when they align with beliefs they already have for other reasons. In the same survey1

- 35% of people feel science can be used to produce any conclusion the researcher wants. The idea that science is not actually a method for generating knowledge or understanding but rather a propaganda tool undermines confidence in scientific information needed to make sound decisions, as individuals and societies.2

- About one-third of people felt that if science didn’t exist at all, their everyday lives wouldn’t be that different.1

- As many as 15-20% of adults in the U.S. believe vaccines probably or definitely cause autism, despite decades of robust scientific evidence showing that this is not true.2

WHAT IS THE CAUSE?

Idols of the Tribe & the Cave- Psychological Causes

These are errors we make either because of how our brains function in general as a species, or particular sources of error that we have as individuals based on our personal experiences and inclinations.

Cognitive biases are systematic pattern of thinking arising from intrinsic features of our cognitive mechanisms. Research in psychology has uncovered an enormous number of cognitive biases that all human beings are prone to. These errors arise from faults in our memory, from quirks in how we direct our attention, and from the influence of our beliefs, desires, and expectations on what we observe. Many of these errors have direct relevance to clinical decision-making, and much of the methodology of science and evidence-based medicine (EBM) is designed specifically to correct for them.3

Logical fallacies are another psychological error source. These are arguments that are wrong, they’re invalid, and they don’t work – but they feel intuitively right and so are very hard to overcome. One example is the “false cause” fallacy. This states that if one event precedes another, the first event likely caused the second. The case of vaccines and autism is a paradigmatic example. Because children get vaccinated around the same time that autism symptoms emerge, there is a correlation in time. Because of the powerful force of this fallacy, it is very difficult to convince people this relationship isn’t causal despite strong evidence against it.

Idols of the Theater- Sociocultural Causes

Our beliefs about scientific topics are part of a larger understanding of the world we inhabit, and these beliefs are influenced by others. There is a strong psychological and social drive to keep all of these beliefs as consistent and coherent as possible and not to threaten our sense of belonging in social groups by challenging beliefs associated with membership. Political affiliation and religious beliefs are the predominant sociocultural influences that alter our views on scientific topis regardless of the objective evidence. These influences can often be quite arbitrary, and change over time.

A powerful recent example is the shift in views of science over the last forty years. In the 1970s, people with politically conservative affiliations tended to be strongly pro-science, associating science and technology with economic growth and military power. Those further to the left politically tended to be suspicious of science, as they were suspicious of industry and the military, and favorably inclined to alternative medicine and related ideas. This relationship has shifted dramatically, and today those professing a conservative political view are more likely to doubt science and scientific experts whereas slogans such as “Trust the Science” have become more common on the political Left. It is not science or scientific evidence which has changed, but the relationship between science and political identity.

Idols of the Marketplace- The Information Ecosystem

While it is by no means the only factor, there is no question that the internet plays a role in the growth of mistrust and misinformation about science. Social media, in particular, is driven by engagement. The algorithms, which prioritize some content and deprioritize other content, particularly amplify the extremes and controversy. Inflammatory content generates more active engagement, positive or negative, than more neutral or nuanced, fact-based content. Because of this, misinformation spreads faster and reaches more people than facts.

The internet also facilitates the creation of echo chambers. We now have the option of selecting our information sources at a very granular level so that we need not ever be bothered by information that contradicts our views if we don’t want to. This makes it very easy for us to become convinced that our beliefs, however mistaken or contrary to the evidence, are widely shared because the only people we interact with are people who think the same way. This amplifies misinformation, increases confidence in false beliefs, and locks people away from information that might challenge them and cause them to rethink.

WHAT IS THE HARM?

The World Health Organization has a whole set of resources to combat what it calls the “Infodemic-” the flood of information available to the public during a public health crisis. The U.S. Surgeon General also issued a report in 2021 address the critical importance of combatting misinformation and mistrust about public health.

The COVID pandemic was a strong example of an infodemic. Information was so voluminous that it overwhelmed people, and some began to tune out entirely, thereby missing important messages from reliable sources. There was also a lot of misinformation, and a lot of contradiction, which is confusing. All of that led to poor decision-making on the part of individuals and groups.

An analysis from the Brown School of Public Health estimated as many as 300, 000 adults in the United States died of COVID who would not have died had everyone eligible for the vaccine got it when it was available. The study also found that those individuals exposed to misinformation about vaccines were significantly less likely to be vaccinated, leading to an increased morbidity and mortality risk.

Mistrust and myths about science also harm those in science-based professions. Healthcare providers and public health officials have been subjected to historic levels of abuse, threats, and even violence from people misled into believing that the healthcare professions are a threat to them. This has exacerbated the flight from these fields and the resulting scarcity of healthcare services and public health expertise.

WHAT IS THE CURE?

There is no cure. Many of the roots of these problems are intrinsic to human cognition and social behavior, and those causes will almost certainly stay with us. However, there are treatments, measures we can take to build and maintain public trust in science and mitigate the harm misinformation does. These are the steps I recommend for veterinarians to combat this problem:

- Be an expert

- Understand misinformation and mistrust

- Be an effective communicator

- Show Up!

Veterinarians have extensive knowledge of science and medicine. Building and maintaining this knowledge base through conscientious, evidence-based medicine practices and then sharing this with our colleagues and clients is a natural and critical part of our role. Information challenging misinformation is most potent when it comes from trusted sources, and we are among the most trusted professions.

Understanding the causes of mistrust and false beliefs is necessary to combat them. If we write off people who distrust science or question our recommendations as stupid or hopeless, we cede the field to those who mislead them. Understanding how people find and maintain anti-science beliefs helps us immunize and treat them.

Likewise, understanding what makes for effective science communication gives our input more impact. There are many resources available to help us learn effective science communication skills, with clients and as members of our personal and professional communities.

Finally, we can have no impact if we don’t participate in the conversation. Be an advocate for your patients and your clients, so that they aren’t misled into things that are harmful. Be and advocate for your colleagues, and support them when they’re attacked and abused for saying things that are appropriate and truthful. Be and advocate for your community; participate in conversations about scientific issues in your community because you have a voice, and it’s an important one, and it can make a difference.

KEY “TAKE HOME” POINTS

- Misinformation and mistrust of science is widespread and growing

- The roots of this problem are many and complex. The main categories are

- Psychological causes intrinsic to how our brains operate

- Sociocultural causes related to our group affiliations

- Ideologies and belief systems that influence how we interpret information about scientific subjects

- The information ecosystem and how it prioritizes engagement and emotion over evidence

- Misinformation leads to poor individual and community decision making, with serious negative consequences for the health and wellbeing of individuals and society. It also encourages abuse and burnout among healthcare professionals, reducing our quality of life and the availability of these critical services.

- There is no single answer to the problem. Veterinarians can help to support science and combat misinformation by

- Developing and maintaining our science-based expertise

- Understanding the causes of mistrust and the factors that support medical misinformation

- Learning to be effective communicators about science

- Actively participating in the discussion and using our expertise and position of trust for the good of our patients, colleagues, and communities.

REFERENCES

- 3m. State of Science Index: 2020 Global Report. 2020. Accessed at: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1898512o/3m-sosi-2020-pandemic-pulse-global-report-pdf.pdf

- Pew research center survey. 2022. Accessed at: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/americans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/

- McKenzie, BA. Veterinary clinical decision-making: cognitive biases, external constraints, and strategies for improvement. J Amer Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(3):271-276.

- Misinformation Resources discussed or cited in this presentation.

Those further to the left politically tended to be suspicious of science, as they were suspicious of industry and the military, and favorably inclined to alternative medicine and related ideas.>>>> Studys published in the BMJ show that except for techical editing peer review of medical journals just giving doctors a chance to stab each other in the back. I guess thats what political identity does to us.

the editor of the bmj at the time the article about peer review was publiished lost his job and the peer review article is now under the control of another editor and now is behind a paywall

“Richard Smith, who edited the BMJ between 1991 and 2004, told the Royal Society’s Future of Scholarly Scientific Communication conference on 20 April that there was no evidence that pre-publication peer review improved papers or detected errors or fraud.

Referring to John Ioannidis’ famous 2005 paper “Why most published research findings are false”, Dr Smith said “most of what is published in journals is just plain wrong or nonsense”. He added that an experiment carried out during his time at the BMJ had seen eight errors introduced into a 600-word paper that was sent out to 300 reviewers.

“No one found more than five [errors]; the median was two and 20 per cent didn’t spot any,” he said. “If peer review was a drug it would never get on the market because we have lots of evidence of its adverse effects and don’t have evidence of its benefit.”

He added that peer review was too slow, expensive and burdensome on reviewers’ time. It was also biased against innovative papers and was open to abuse by the unscrupulous. He said science would be better off if it abandoned pre-publication peer review entirely and left it to online readers to determine “what matters and what doesn’t”.

“That is the real peer review: not all these silly processes that go on before and immediately after publication,” he said.