Food is Love

As a child, I was a big fan of the Peanuts cartoons. One of my favorite characters was Snoopy, a suave, bipedal beagle who wrote novels and engaged in breathtaking aerial combat with his nemesis, the Red Baron. Though Snoopy was unlike most other beagles I have known, he had one characteristic common to others of his breed, and indeed most dogs. When suppertime arrived, all other activities were forgotten, and he often launched into an exuberant, joyful suppertime dance. Every feeding was a celebration for Snoopy, a celebration not only of food but of the bond between dog and owner.

Few subjects generate the same intensity of emotion in pet owners as the question of what to feed our animal companions. Feeding our pets is the quintessential act of caring and love. And based on how most dogs and cats act at feeding time, it certainly seems like a highlight of the relationship for them!

There is also a deep sense in most pet owners that choosing a pet food has tremendous significance for the health and well-being of their pets. Everyone wants to give their pets the “best” food, the food that will keep them active and happy and prevent illness for as long as possible. We have all been told most of our lives that what we eat affects our health, so we want to make good, healthy nutritional choices for our pets as well.

The food we give our pets food is also something we have control over. We naturally want to do everything we can to ensure our pets stay healthy, but many factors that influence the risk of disease are beyond our control. Food, at least, is something tangible that we know has an influence on health, and we can make choices about what we feed our pets that give us a sense of actively influencing their health.

The significance and emotion attached to feeding can be good in that it motivates pet owners to seek information and try to make thoughtful, informed choices about what to feed. However, the pressure to find the “right” food can also make clients vulnerable to irrational decisions, and to exaggerated or unproven claims about nutrition and health. Like most medical subjects, nutrition is complicated and full of uncertainty and nuance, and the desire to find the perfect food to guarantee our pets good health is all too easy to exploit by those selling pet food or promoting particular feeding ideologies. Even smart, rational people can get swept away by enthusiasm or diet fads that may not be based on reliable scientific principles or evidence.

The role of veterinarians in decisions about nutrition is critical. We should be a reliable and convenient resource for owners, supporting rational feeding choices. But are we? Do pet owners rely on their vets for guidance about nutrition, and do we live up to our responsibility to provide it?

Do Clients Trust Us?

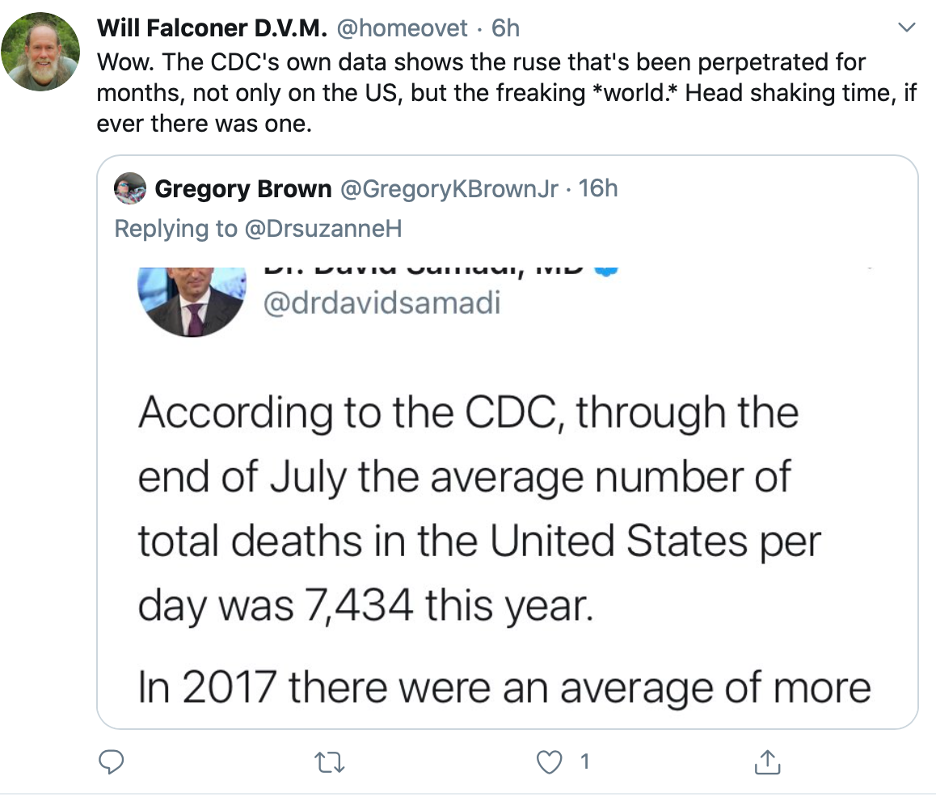

Unfortunately, the idea that veterinarians are not reliable sources of nutrition information is widespread. Many voices, from the media and breeders and even some of our colleagues within the profession, are loudly proclaiming that vets know little or nothing about pet nutrition, that what we do know is mere pet food industry propaganda, and that we are more concerned with selling food than with using nutrition to support the health of our patients [see examples below].

In general, the public sees vets as pretty trustworthy and likeable, sometimes even more so that other healthcare professionals.1 While there is some variability among studies in the extent to which pet owners trust our advice about nutrition, most show that a majority of clients desire advice from their vet on what to feed and have high confidence in this advice.2–7 However, the full picture is more complicated. The extent to which clients use and trust veterinary advice on nutrition varies with characteristics of owners, the pets they own, and the type of diets they choose to feed.

Not surprisingly, for example, owners feeding non-traditional diets rather than commercial pet food express less confidence in veterinary nutrition advice.4,7,8 One study found that owners feeding raw animal products to their pets were much less confident in veterinary nutrition advice than those not feeding any raw foods.4 About 54% of clients who did not feed raw trusted this advice “very much” while only 13% of raw feeders had this level of confidence.

This seemed to generalize beyond nutrition to medical advice in general. In one study, advice about topics other than nutrition was considered highly trustworthy by 64% of clients who did not feed raw products, but only 36% of those clients who did.4 Raw feeders are less likely to trust veterinary recommendations about vaccination, flea control and other preventative health interventions.4,9 This suggests that pet owners who feed unconventional diets may have a broader distrust of conventional veterinary medicine and a more favorable view of alternative medicine.

Such a connection between unconventional nutritional practices and a general distrust of science-based veterinary medicine seems likely given the consistent criticism of vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and other science-based interventions by veterinarians advocating for raw or other unconventional diets.10–12

Even those suspicious of veterinary medicine in general and committed to feeding their pets unconventional diets, however, still have some interest in veterinary nutrition advice. In one survey, 50% of raw feeders trusted veterinary advice in general “somewhat,” and 32% had this level of confidence in the nutrition knowledge of their vet.4 Surprisingly, among cat owners, a majority reported choosing to feed raw was influenced by advice from their veterinarian (58%) or from other veterinary sources (78%).4 This suggests that the problem may not necessarily be a true lack of trust in veterinarians as a source of advice about nutrition so much as a desire to follow veterinary advice so long as it is consistent with other values or beliefs related to pet health. Owners who feed raw or other unconventional diets, for example, often hold beliefs about the health benefits of such diets that have not been scientifically validated and which are unlikely to be affirmed by most veterinarians. However, these beliefs may be supported by vets with alternative philosophies or approaches, and raw feeders are likely to trust such vets more because their views are aligned.4,7–9,13

Another factor influencing both client feeding choices and their degree of trust in veterinarians as a source of information about nutrition is attitudes towards pet food producers. Pet owners, particularly those feeding unconventional diets, often express significant distrust in the motives and claims of commercial diet manufacturers and in the health value of commercial foods.2,4,8,9

Commercial pet diets are sometimes seen as “junk food,” equivalent in nutritional and health value to human convenience and snack foods because both are “processed.” Pet owners sometimes express concerns about the health effects of grains, organic versus conventional ingredients, genetically-modified ingredients, meat from animals that are ill or have died or been euthanized, and other real or imagined components of commercial diets. There have also been some very serious incidents of real harm to pets from adulterated or contaminated commercial diets, and many pet owners are aware of these.14 Such concerns undermine confidence not only in pet food manufacturers but in veterinarians because we are seen recommending primarily commercial diets and as having potential financial and other conflicts of interest that influence these recommendations.

Should Clients Trust Us?

The arguments against heeding veterinary advice about nutrition are ultimately bad arguments which lead clients to make decisions based on misinformation, fear, marketing propaganda, and other unreliable foundations. Like many bad arguments, however, there is some core of truth to each of them that we have to address in order to protect our clients from being misled.

What Do Vets Know about Nutrition?

The idea that veterinarians (or at least those practicing conventional science-based medicine) know nothing about nutrition is false. All veterinarians learn about the importance of nutrition and about the effect of food and feeding practices on health in veterinary school. Some of this education is in dedicated nutrition courses, but most of it is incorporated into our education about specific species and health conditions and into our hands-on clinical training.

However, there is no denying that the quantity and quality of the nutrition education most vets receive is insufficient. Many veterinary schools do not have full-time board-certified veterinary nutritionists on faculty teaching courses in nutrition.15 Surveys of veterinarians consistently find that while we understand the importance of nutrition in health, we rarely feel confident in our training or ability to provide nutritional counseling.15–19 Apart from the small number of board-certified nutritionists, most small-animal veterinarians cannot fairly claim to be experts in pet nutrition.

So are the critics right? I would argue they are not. While most veterinarians would like more and better training about nutrition than they have, we are still well equipped to offer pragmatic, science-based advice. We have both the general knowledge of physiology and nutrition and the ability to critically evaluate new research and incorporate it into our recommendations. This equips us to offer sound advice about nutrition to our clients.

Crucially, the alternative sources that clients turn to when they don’t trust their veterinarian’s nutrition knowledge are unquestionably less informed and less reliable. Companies marketing unconventional diets, breeders and other lay persons with little or no scientific training, and the information jungle that is the Internet cannot provide the quality or reliability of advice about nutrition that we can as veterinarians.

Proponents of unconventional feeding practices, including many veterinarians committed to alternative medical approaches, will tell clients and conventional veterinarians that they are nutrition experts because they have “educated” themselves, above and beyond the information most veterinarians receive in school. This “education,” however, is nothing more than seeking and accepting ideas and claims that lack scientific validation but conform to the ideological biases these advocates bring to their search.

The claim that dogs should eat a “species appropriate” diet extrapolated from what wolves or other wild canids might eat is a common example of this kind of ideologically motivated false expertise. Dogs are not wolves, and they have significant anatomic and functional differences between wolves and domestic dog. Many of these involve their systems for eating and digesting food. For all the millennia dogs have lived with humans, they have scavenged our leftovers and shared our food, and evolution has adapted them to a much more varied and less meat-centered diet than wolves or many other wild canids.20–25

Similarly, unsupported claims about the dangers of grains and carbohydrates,26–31 the benefits of raw32–35 and organic36–40 ingredients, the risks of genetically modified ingredients41–44 and various preservatives or other food additives45, and many other such ideas are frequently identified as examples of advanced knowledge or understanding that most vets lack. However, these do not constitute reliable or scientifically informed advice. Most of these claims are unsupported by good evidence, and many are clearly wrong. Even with the inadequacies in our nutrition training, we are a more reliable source of information and advice for pet owners about nutrition than the alternatives they may turn to if they lose trust in us.

Is all Our Knowledge Just Industry Propaganda

Once again, there is some legitimacy to the claim that the pet food industry has a biased perspective on pet nutrition, and that this industry has entirely too much influence on veterinary education and the veterinary profession. The giving of gifts from industry representatives has been clearly linked to prescribing behavior in physicians,46,47 and it is unlikely that veterinarians are immune to this effect. The common practice of showering students and practitioners with gifts, from coffee mugs to free food to vacations nominally intended as “continuing education,” is a real threat to both the true objectivity of veterinarians and the trust of our clients. Such practices should absolutely be discouraged.

Similarly, there is good evidence that industry funding influences the outcomes of clinical research in ways that is often in favor of the funder’s products.48,49 The concern that the scientific foundations for our recommendations about nutrition may reflect the biases of industry are not unfounded. Fortunately, the impact of such sponsorship bias on research can be mitigated with appropriate methods for controlling bias50, from trial registration and a priori publication of research protocols to strict policies banning any involvement by the funder in the design, conduct, and analysis of research studies. Ideally, more independent funding from academic institutions, non-profit organizations, and government entities would also help to reduce the influence of industry on research, though such funders have, of course, their own biases.

Once again, however, we must understand that these legitimate concerns about potential bias in the information veterinarians receive and provide concerning pet nutrition does not validate the dismissal of veterinary advice nor the acceptance of alternative information sources. We cannot simply declare all nutrition research worthless due to industry bias and make up whatever alternative theories or facts suit us. All data in science comes with limitations, and all conclusions are provisional and must be altered over time as the quality of our data improves. Such evidence is still, however, far superior to the unsubstantiated theories, intuition, and uncontrolled personal experience usually cited in support of alternative nutritional practices.

It is also often overlooked that all scientific research incorporates biases of others kinds as well, beyond simply that of funding source, and that this influences research results as much or more than the funding source.51 Studies funded by companies producing unconventional diets or conducted by dedicated evangelists for such diets, are no less susceptible to bias than those funded by conventional pet food companies.

Concerns raised in 2018 about potential negative health effects of grain-free and other unconventional diets52–54, for example, were recently strongly challenged in a narrative literature review.55 This review generated some controversy when the authors turned out to have financial ties to a prominent manufacturer of grain-free dog food. Conflict of interest and bias are ubiquitous and not limited to research supporting conventional or commercial diets. We must evaluate all claims and all evidence critically and be mindful of potential bias while not giving up on evidence-based medicine, which has proved its superiority to anecdote and opinion beyond question.

Veterinarians’ understanding of nutrition science and the physiology of our patients is sound The evidence for many specific nutritional interventions is quite strong;56 certainly stronger than that for the sort of claims offered by those who claim our knowledge is biased and worthless. Tens of thousands of dogs and cats thrive on conventional diets for many years, and while we will likely discover ways to significantly improve how and what we feed through future research, the notion that these diets are grossly inappropriate or harmful is nonsense. Until the alternatives to these diets can generate evidence at least as good as that for current practices, it is disingenuous to dismiss veterinary nutrition counseling on the basis of perceived industry bias.

Do Vets Care More About Selling Food than Patient Health?

I suspect no one will be surprised that my answer to this question is an emphatic “No!” Veterinarians do make money selling pet food, especially therapeutic diets intended for management of medical conditions such as chronic kidney disease, urinary tract stones, food allergies, and others. This is changing as online sales grow, and far more pet food is purchased from sources other than veterinary clinics and hospitals.57 However, food is a revenue stream just as are all the other medications, procedures, and services we provide for our patients.

While financial incentives can influence the behavior of veterinarians and other healthcare providers, the idea that this is central motivation or that we would sacrifice patient health for profit is nonsense. Veterinarians are individuals committed to animal welfare, and there is no question we could make far more money in much easier jobs if that were our primary concern. Given the training, hard work, stress, and debt we take on to be part of this profession, none of us are the sort of people who would sacrifice our patients or our ethics for the revenue we get from selling pet food. Very few of my clients buy their food from my hospital, and I routinely direct owners to reliable sources for fresh commercial and balanced homemade diets formulated by veterinary nutritionists.

Unfortunately, the folks who are likely to believe vets are greedy and unconcerned about their patients’ welfare aren’t likely to be swayed by any argument or evidence. I will, however, point out that once again the alternatives to conventional diets also nearly all make money for someone, whether they are manufactured alternative diets, books written by veterinarians to promote such diets, or consultation fees these vets charge for the time they spend teaching clients about their views on nutrition. No one taking any position on what constitutes healthy nutrition for dogs and cats is doing so without some sort of bias, and potential financial bias is as likely on either side of the debate.

How Can We Best Help Our Clients?

The bottom line is that veterinarians have useful, reliable information to offer clients about nutritional choices for their pets. There is good scientific evidence to support many of our recommendations, from low-calcium and reduced calorie diets for large-breed puppies58–64 to specially formulated renal diets for elderly cats with chronic kidney disease65. As general practitioners, our fundamental understanding of physiology and nutrition is sound and useful even though we are not nutrition specialists, just as our understanding of heart disease and diabetes is sound and useful even though we are not boarded cardiologists or internists. We must recognize our own strengths and use what we know to support our clients in making well-informed choices.

One of the most useful insights we can offer many clients is that there is no “perfect” diet that will guarantee only good health for their pets, and there are few diets that are egregiously “toxic” and certain to lead to illness. Health is a complex and multifactorial state, and while nutrition is unquestionably important, simplistic notions or good and bad foods or ingredients and excessive anxiety about finding the “right” foods do more harm than good. An unhealthy obsession with selecting very specific or extreme diets for perceived health values is now widely recognized as an eating disorder in humans, usually referred to as “orthorexia.”66 Pet owners may be subject to a similar unrealistic obsession with nutrition as a means of warding off disease in their pets.

Helping pet owners to make good choices about nutrition includes helping reduce the pressure they feel that every choice is critical and will make or break their pets’ health. This is an understanding we have as healthcare professionals and which we can share with our clients.

We must also, as always, strive to do better in the area of nutrition as in all aspects of our work. Practitioners should see pursuing continuing education in nutrition from reputable sources as a necessary part of our professional development. Veterinary schools should make nutrition a stronger element of the curriculum. And we should recognize the limits of our expertise and be prepared to refer clients when they need nutritional guidance we cannot provide. Board-certified nutritionists in academic and private practice can be excellent resources in developing optimal nutritional plans for individual patients and in countering the ubiquitous myths and misinformation our clients may be exposed to.

Finally, we should acknowledge the legitimate elements in the criticism of our knowledge and practices. While the pet food industry produces many healthful products and generates much useful resources, profit motives do influence the evidence and the education associated with industry. Clinicians need to be less eager to accept gifts and favors from representatives of industry, and we need to incorporate a recognition of potential funding bias in our critical evaluation of research evidence in the area of nutrition. The best answer to our critics and those promoting unsubstantiated and unscientific alternative approaches to evidence-based nutrition advise is not to cede the field but to work harder to meet our responsibilities to our clients and our patients.

References

1. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. Vets amongst the most trusted professionals, according to survey – Professionals. RCVS News. https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/news/vets-amongst-the-most-trusted-professionals-according-to-rcvs/. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2020.

2. Michel KE, Willoughby KN, Abood SK, et al. Attitudes of pet owners toward pet foods and feeding management of cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233(11):1699-1703. doi:10.2460/javma.233.11.1699

3. Evason M, Peace M, Munguia G, Stull J. Clients’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to pet nutrition and exercise at a teaching hospital. Can Vet J. 2020;61(5):512-516. https://www.cabi.org/vetmedresource/abstract/20203199863. Accessed August 23, 2020.

4. Morgan SK, Willis S, Shepherd ML. Survey of owner motivations and veterinary input of owners feeding diets containing raw animal products. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3031. doi:10.7717/peerj.3031

5. Kamleh M. Perceptions and attitudes towards human and companion animal nutrition, nutrition education and nutrition guidance received from healthcare professionals. 2019. https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10214/17482/Kamleh_May_201909_PhD.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y. Accessed September 7, 2020.

6. Flocke A, Thiemevera H, Kiefer-Hecker B. Dog and cat nutrition practices of owners visiting veterinary clinics. In: 17th Congress of the ESVCN. Ghent, Belgium; 2013.

7. Connolly KM, Heinze CR, Freeman LM. Feeding practices of dog breeders in the United States and Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245(6):669-676. doi:10.2460/javma.245.6.669

8. Morelli G, Bastianello S, Catellani P, Ricci R. Raw meat-based diets for dogs: survey of owners’ motivations, attitudes and practices. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):74. doi:10.1186/s12917-019-1824-x

9. Lenz J, Joffe D, Kauffman M, Zhang Y, LeJeune J. Perceptions, practices, and consequences associated with foodborne pathogens and the feeding of raw meat to dogs. Can Vet J. 2009;50(6):637. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684052/. Accessed August 24, 2020.

10. Dodds WJ, Laverdure D. Canine Nutrigenomics?: The New Science of Feeding Your Dog for Optimum Health.; 2015. https://www.worldcat.org/title/canine-nutrigenomics-the-new-science-of-feeding-your-dog-for-optimum-health/oclc/890808034&referer=brief_results. Accessed October 27, 2018.

11. Pitcairn RH, Pitcairn SH. Dr. Pitcairn’s Complete Guide to Natural Health for Dogs & Cats.; 2017. https://www.worldcat.org/title/dr-pitcairns-complete-guide-to-natural-health-for-dogs-cats/oclc/948336415&referer=brief_results. Accessed October 27, 2018.

12. Billinghurst I. Give Your Dog a Bone.; 1993. https://www.worldcat.org/title/give-your-dog-a-bone/oclc/973482033&referer=brief_results. Accessed October 27, 2018.

13. Dodd SAS, Cave NJ, Adolphe JL, Shoveller AK, Verbrugghe A. Plant-based (vegan) diets for pets: A survey of pet owner attitudes and feeding practices. Suchodolski JS, ed. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210806. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210806

14. Bischoff K, Rumbeiha WK. Pet Food Recalls and Pet Food Contaminants in Small Animals: An Update. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2018;48(6):917-931. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.07.005

15. Becvarova I, Prochazka D, Chandler ML, Meyer H. Nutrition Education in European Veterinary Schools: Are European Veterinary Graduates Competent in Nutrition? J Vet Med Educ. 2016;43(4):349-358. doi:10.3138/jvme.0715-122R1

16. Bruckner I, Handl S. Survey on the role of nutrition in first?opinion practices in Austria and Germany: An evaluation of knowledge, preferences and need for further education. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). June 2020:jpn.13337. doi:10.1111/jpn.13337

17. Kamleh MK, Khosa DK, Dewey CE, Verbrugghe A, Stone EA. Ontario Veterinary College First-Year Veterinary Students’ Perceptions of Companion Animal Nutrition and Their Own Nutrition: Implications for a Veterinary Nutrition Curriculum. J Vet Med Educ. May 2020:e0918113r1. doi:10.3138/jvme.0918-113r1

18. Lumbis RH, Scally M. Knowledge, attitudes and application of nutrition assessments by the veterinary health care team in small animal practice. J Small Anim Pract. 2020;61(8):494-503. doi:10.1111/jsap.13182

19. Abood SK. Teaching and Assessing Nutrition Competence in a Changing Curricular Environment. J Vet Med Educ. 2008;35(2):281-287. doi:10.3138/jvme.35.2.281

20. Serpell J. The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People. 2nd ed. (Serpell J, ed.). Cambridge University Press; 2017.

21. Sturgeon A, Jardine CM, Weese JS. COMPARISON OF THE FECAL MICROBIOTA OF WILD WOLVES, DOGS FED COMMERCIAL DRY DIETS AND DOGS FED RAW MEAT DIETS. In: Proceedings 2014 ACVIM Research Forum. Vol 28. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111); 2014:1346-1374. doi:10.1111/jvim.12375

22. Axelsson E, Ratnakumar A, Arendt M-L, et al. The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet. Nature. 2013;495(7441):360-364. doi:10.1038/nature11837

23. Ziesenis A, Wissdorf H. [The ligaments and menisci of the femorotibial joint of the wolf (Canis lupus L., 1758)–anatomic and functional analysis in comparison with the domestic dog (Canis lupus f. familiaris)]. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb. 1990;136(6):759-773. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2099308. Accessed December 28, 2018.

24. Wayne RK. Molecular evolution of the dog family. Trends Genet. 1993;9(6):218-224. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8337763. Accessed December 28, 2018.

25. Reiter T, Jagoda E, Capellini TD. Dietary Variation and Evolution of Gene Copy Number among Dog Breeds. 2016. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148899

26. Laflamme D, Izquierdo O, Eirmann L, Binder S. Myths and Misperceptions About Ingredients Used in Commercial Pet Foods. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2014;44(4):689-698. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2014.03.002

27. Murray SM, Fahey GC, Merchen NR, Sunvold GD, Reinhart GA. Evaluation of selected high-starch flours as ingredients in canine diets. J Anim Sci. 1999;77(8):2180-2186. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10461997. Accessed December 18, 2018.

28. de-Oliveira LD, Carciofi AC, Oliveira MCC, et al. Effects of six carbohydrate sources on diet digestibility and postprandial glucose and insulin responses in cats1. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(9):2237-2246. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0354

29. Bazolli RS, Vasconcellos RS, de-Oliveira LD, Sá FC, Pereira GT, Carciofi AC. Effect of the particle size of maize, rice, and sorghum in extruded diets for dogs on starch gelatinization, digestibility, and the fecal concentration of fermentation products1. J Anim Sci. 2015;93(6):2956-2966. doi:10.2527/jas.2014-8409

30. Carciofi AC, Takakura FS, de-Oliveira LD, et al. Effects of six carbohydrate sources on dog diet digestibility and post-prandial glucose and insulin response. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2008;92(3):326-336. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00794.x

31. Laflamme D. Cats and carbohydrates: Why is this still controversial? In: 2018 ACVIM Forum. Seattle, WA; 2018.

32. McKenzie B. Debating Raw Diets. Vet Pract News. January 2019:30-31. https://www.veterinarypracticenews.com/debating-raw-diets-january-2019/.

33. Freeman LM, Chandler ML, Hamper BA, Weeth LP. Current knowledge about the risks and benefits of raw meat-based diets for dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243(11):1549-1558. doi:10.2460/javma.243.11.1549

34. Schlesinger DP, Joffe DJ. Raw food diets in companion animals: a critical review. Can Vet J = La Rev Vet Can. 2011;52(1):50-54. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21461207. Accessed October 27, 2018.

35. Gyles C. Raw food diets for pets. Can Vet J = La Rev Vet Can. 2017;58(6):537-539. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28588324. Accessed December 28, 2018.

36. Bara?ski M, ?rednicka-Tober D, Volakakis N, et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(05):794-811. doi:10.1017/S0007114514001366

37. ?rednicka-Tober D, Bara?ski M, Seal CJ, et al. Higher PUFA and n-3 PUFA, conjugated linoleic acid, ?-tocopherol and iron, but lower iodine and selenium concentrations in organic milk: a systematic literature review and meta- and redundancy analyses. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(06):1043-1060. doi:10.1017/S0007114516000349

38. Dangour AD, Dodhia SK, Hayter A, Allen E, Lock K, Uauy R. Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):680-685. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28041

39. Mie A, Andersen HR, Gunnarsson S, et al. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):111. doi:10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4

40. Smith-Spangler C, Brandeau ML, Hunter GE, et al. Are Organic Foods Safer or Healthier Than Conventional Alternatives? Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):348. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00007

41. Landrum AR, Hallman WK, Jamieson KH. Examining the Impact of Expert Voices: Communicating the Scientific Consensus on Genetically-modified Organisms. Environ Commun. August 2018:1-20. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1502201

42. National Academies of Sciences E and M. Genetically Engineered Crops. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2016. doi:10.17226/23395

43. Van Eenennaam AL, Young AE. Prevalence and impacts of genetically engineered feedstuffs on livestock populations1. J Anim Sci. 2014;92(10):4255-4278. doi:10.2527/jas.2014-8124

44. Nicolia A, Manzo A, Veronesi F, Rosellini D. An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2014;34(1):77-88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595

45. McKenzie B. Is banning “artificial” ingredients based on fear or science? Vet Pract News. March 2019:36-37.

46. King M, Bearman PS. Gifts and influence: Conflict of interest policies and prescribing of psychotropic medications in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2017;172:153-162. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.010

47. Grande D, Frosch DL, Perkins AW, Kahn BE. Effect of Exposure to Small Pharmaceutical Promotional Items on Treatment Preferences. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):887. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.64

48. Fabbri A, Lai A, Grundy Q, Bero LA. The Influence of Industry Sponsorship on the Research Agenda: A Scoping Review. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):e9-e16. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304677

49. Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2017;2:MR000033. doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3

50. Ioannidis JPA. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001747. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001747

51. Ioannidis JPA. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLoS Med. 2005;2(8):e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

52. Freeman LM, Stern JA, Fries R, Adin DB, Rush JE. Diet-associated dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs: what do we know? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253(11):1390-1394. doi:10.2460/javma.253.11.1390

53. Kaplan JL, Stern JA, Fascetti AJ, et al. Taurine deficiency and dilated cardiomyopathy in golden retrievers fed commercial diets. Loor JJ, ed. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209112

54. Adin D, DeFrancesco TC, Keene B, et al. Echocardiographic phenotype of canine dilated cardiomyopathy differs based on diet type. J Vet Cardiol. 2019;21:1-9. doi:10.1016/J.JVC.2018.11.002

55. McCauley SR, Clark SD, Quest BW, Streeter RM, Oxford EM. Review of canine dilated cardiomyopathy in the wake of diet-associated concerns. J Anim Sci. 2020;98(6). doi:10.1093/jas/skaa155

56. Davies M. Veterinary clinical nutrition: success stories: an overview. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(03):392-397. doi:10.1017/S002966511600029X

57. An Uptick in Clicks and Bricks for Pet Food: An Omnichannel Perspective – Nielsen. Nielsen.com. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2018/an-uptick-in-clicks-and-bricks-for-pet-food-an-omnichannel-perspective/. Published 2018. Accessed September 7, 2020.

58. Schoenmakers I, Hazewinkel HA, Voorhout G, Carlson CS, Richardson D. Effects of diets with different calcium and phosphorus contents on the skeletal development and blood chemistry of growing great danes. Vet Rec. 2000;147(23):652-660. doi:10.1136/VR.147.23.652

59. Dobenecker B. Influence of Calcium and Phosphorus Intake on the Apparent Digestibility of These Minerals in Growing Dogs. J Nutr. 2002;132(6):1665S-1667S. doi:10.1093/jn/132.6.1665S

60. Dämmrich K. Relationship between Nutrition and Bone Growth in Large and Giant Dogs. J Nutr. 1991;121(suppl_11):S114-S121. doi:10.1093/jn/121.suppl_11.S114

61. Kasström H. Nutrition, Weight Gain and Development of Hip Dysplasia. Acta Radiol Diagnosis. 1975;16(344_suppl):135-179. doi:10.1177/0284185175016S34412

62. Hedhammar A, Krook L, Whalen JP, Ryan GD. Overnutrition and skeletal disease. An experimental study in growing Great Dane dogs. IV. Clinical observations. Cornell Vet. 1974;64(2):Suppl 5:32-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4826269. Accessed September 11, 2020.

63. Kealy RD, Lawler DF, Ballam JM, et al. Five-year longitudinal study on limited food consumption and development of osteoarthritis in coxofemoral joints of dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;210(2):222-225. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9018356. Accessed September 11, 2020.

64. Lauten SD. Nutritional risks to large-breed dogs: from weaning to the geriatric years. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(6):1345-1359, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.003

65. Davies M. Veterinary clinical nutrition: success stories: an overview. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(03):392-397. doi:10.1017/S002966511600029X

66. Cena H, Barthels F, Cuzzolaro M, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(2):209-246. doi:10.1007/s40519-018-0606-y

Examples of Negative Propaganda about Vets and Nutrition

Don’t listen to what your vet has to say about feeding your dog: vets know virtually nothing about animal nutrition… Most veterinarians have ZERO training in nutrition.

My education came from the food company representatives; those that sponsored events while I was a student, and later the food reps that visited the veterinary practices I worked in.

The dog food industry is now dominated by large multinational consumer corporations who, in my opinion, are far more interested in profit than the health of your pet. The entire pet food industry is not on the whole very ethical. Not only do they produce some pretty unhealthy stuff, they also do some pretty unethical things.

Andrew Jones, DVM

Pets Naturally Magazine

March, 2016

Because nutrition isn’t viewed as an integral part of disease management, many vet students graduate not recognizing the monumental role nutrition plays in overall health. They don’t have enough knowledge to institute innovative nutritional protocols to manage degenerative disease in their patients.

Worse still is that at many of the veterinary schools in North America, the instruction vet students DO receive comes from the biggest pet food producers in the business. Needless to say, the “training” the students receive from these companies is heavily slanted in favor of the products they sell, which are inevitably highly processed. Currently, none of the major pet food companies sell biologically appropriate diets, so these foods are portrayed as dangerous.

Unfortunately, the majority of board-certified veterinary nutritionists have also been schooled primarily about processed pet diets, and believe it or not, major pet food manufacturers frequently pay the tuition for DVMs studying to become veterinary nutritionists. So when a veterinary nutritionist recommends X, Y or Z food — or discourages feeding raw or homemade diets, which is common — keep in mind that many practicing veterinary nutritionists are obligated in some way to a pet food manufacturer.

Karen Becker, DVM

Healthy Pets, Mercola.Com

July, 2017

The problem with your average veterinarian giving you nutritional advice is that they have had very little nutrition training… Most vets get their information from other biased or uninformed vets, they believe what they read in the vet publications sponsored by kibble companies, they get their info from sales representatives of the big kibble companies or from limited private reading. I am sure you understand why kibble companies do not make the best reference source as they are only interested in selling their products and are not open to alternative diets even if that might be actually needed.

Jennifer Carter

Volhard Dog Nutrition

January, 2020

How much do veterinarians learn about nutrition? The sad answer is not a lot, and often our information is biased…the doctors graduating from veterinary schools are biased at best. At worst, they are very “anti-natural” and rabid fans of these national brands…Most well-known pet food companies have been sold to mega conglomerates like Colgate-Palmolive, who often add plant and animal by-products and various chemical preservatives, additives, flavorings, and colorings to the products.

Doctors must strike out on their own to seek a more balanced approach to diet and nutrition. But they are not inclined to do this unless they are driven to expand beyond conventional medicine. Since most are satisfied with the status quo, it is hard to find a veterinarian who is not afraid to challenge his long-held beliefs and actually look at other dietary and nutritional options for his patients.

Shawn Messonier, DVM

Animal Wellness Magazine

2008

Hills, Purina, and Iams are ingrained into the consciousnesses of every veterinarian from their professional infancy to their grave. Processed food is in our blood – Yuck. How can you expect a veterinarian to be open to the idea that real, raw food is anything but dangerous for pets?

Veterinary students learn about dog and cat nutrition from a book written by a major pet food company. The nutritionist that teaches them has usually had their education underwritten by a major pet food company. Major pet food companies provide free food for vet students and also the teaching hospitals where they are learning about veterinary norms.

Who has money to fund research into pet nutrition? You guessed it, the major pet food companies. Most continuing education for veterinarians regarding nutrition is sponsored by pet food companies.

My hope is that the grassroots, raw pet food movement will cause more vets to see the light as they encounter healthy animals being fed these diets. Perhaps the conventional nutrition programming can be unlearned and the eyes of veterinarians opened to the truth.

Doug Knueven, DVM

Blog Post

May, 2014