I generally try to stay away from politics per se on this blog, though I often cover political issues when they touch on the areas of science and alternative medicine. Usually, this falls in the general category of government failure to regulate unproven or pseudoscientific therapies properly or protect the public from quackery. However, this post is more directly about the current election. Regardless of your political perspective or which candidate you support on the basis of other issues, there is a bit of information out there concerning the presidential candidates’ positions on science issues, and that is what I’m going to address today.

Since 2008, the non-profit, non-partisan group ScienceDebate has been trying to get all major and third-party candidates for president to participate in a debate specifically focused on science and technology issues. Such a debate, sadly, has never happened, which says a lot about the degree to which science is valued by politicians and voters. However, candidates often provide written answers to questions about science policy, which allows some comparison of their knowledge and views on these topics.

Both Trump and Clinton, as well as Green Party candidate Jill Stein and Libertarian Gary Johnson, provided answers to these questions this year. There isn’t much surprising about these answers.

Clinton

Clinton’s answers reflect a mainstream moderate-left view, and in general she makes moderately specific policy proposals involving increasing government investment and/or regulation. Her responses are the longest and most specific and substantive of the candidates. In particular, she acknowledges anthropogenic climate change and supports international efforts to combat it, and she is a strong proponent of vaccination and public health programs.

Apart from her answers on this questionnaire, Clinton has been frustratingly sympathetic to naturopathy and some varieties of alternative medicine, so she is by no means a crusader for a strongly science-based approach to medicine. And her positions on GMOs have been inconsistent.

Stein

The positions of the minor party candidates also fit pretty closely the expectations one would have based on their political affiliations. Jill Stein’s answers mostly emphasize environmental protection positions, such as aggressive action on climate change. Unfortunately, she also strongly supports a number of positions suggesting she is either misinformed about the scientific evidence or prefers ideology to scientific facts. She aggressively promotes organic agricultures, despite the lack of evidence to support any health benefits. This may be because of perceived environmental benefits, and there is somewhat better evidence for these, though is also controversy on this subject. Stein is also strongly opposed to GMO research and supports misleading labeling laws intended to discourage progress in this area, which reflects a fear of GMO not supported by the evidence.

While Stein has been accused of being anti-vaccine, the evidence does not support that view. She does tend to respond to any question about vaccines by talking mostly about conflict-of-interest issues within regulatory agencies and suggesting that distrust of vaccination is driven more by this than anti-vaccine propaganda. I tend to agree with concerns about conflict-of-interest, but I disagree that this is the major driver of anti-vaccine fears. I think complaints about industry and government relations, even when often valid, are used as a justification for anti-vaccine ideologies based more in pseudoscience and fear than in genuine concern about impartial science. However, her statements suggest that despite this rhetorical focus, she appears to accept the scientific consensus on the safety and benefits of vaccination, she’s just less concerned about those issues than about big bad corporations.

It’s also true that the Green Party platform has been supportive of homeopathy and other alternative therapies. That has been dropped from the current platform, though it was present when Stein was the nominee in 2012. Finally, Stein is also adamantly opposed to any use of nuclear power under any circumstances, without any apparent interest in the scientific evidence concerning the pros and cons of it.

Johnson

Libertarian Gary Johnson, not surprisingly, answers pretty much all of the questions in a way that allows him to emphasize his view that government is almost always the problem and not the solution. He rarely has much to say about the scientific issues per se, since he’s much more concerned about free markets and eliminating most government functions. Though he doesn’t say much about science, his answers generally don’t reveal any significant departures from mainstream science. He even appears, grudgingly and weakly, to accept a role of human activity in climate change and the need for compulsory vaccination, at least sometimes.

Johnson is, however, adamantly opposed to any meaningful regulatory role for the FDA in drug safety, which is clearly counter to the best interests of patients. And I suspect he would support the continued lack of meaningful regulation of dietary supplements, herbal remedies, and so on, in favor of the “buyer beware” approach, which proved utterly ineffective in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Donald Trump

And then there’s Donald Trump. Without question, his ScienceDebate answers and other comments make him soundly the most anti-science candidate running, in terms of positive policy positions and a general ignorance of the issues and the facts. His answers to the questions are typically short, vague, and often completely off point, indicating a total lack of interest in the subject. Overall, he too disdains much role for government in science and technology, preferring the free market to be allowed to do as it pleases. His response to the issue of public health strongly suggests he sees little to no value in the national public health system or institutions.

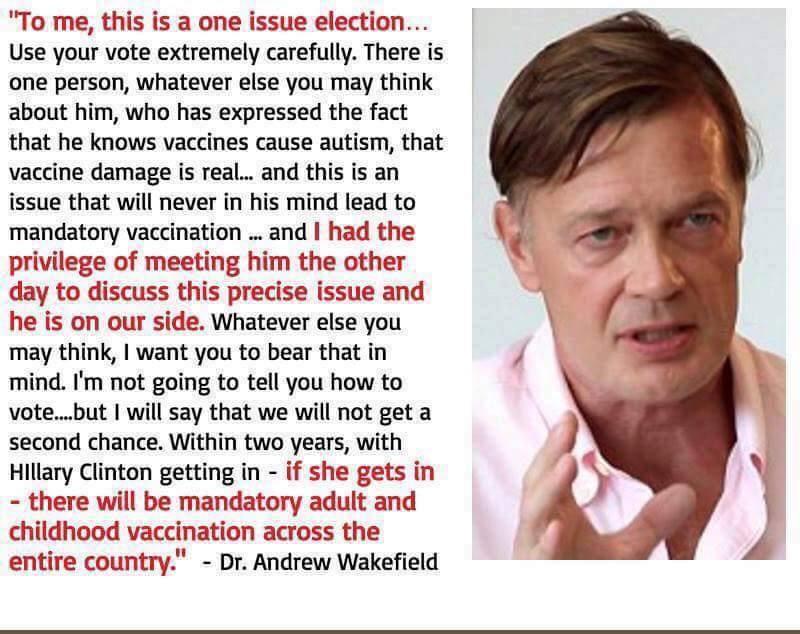

Where Trump sets himself apart from the other candidates in terms of science issues is in his rejection of climate change science and his deeply anti-vaccination views. He has indicated a belief that climate change is not real and is merely a ploy to give China an economic advantage over the U.S. And he is the candidate of choice for the anti-vaccine movement due to his open acceptance of the tired and long-disproven myth that vaccines cause autism. Here are some examples of how popular Trump is with the anti-vaccine crowd.

The keynote conclusion of this article on the notorious quackery site is this:

This November, VOTE TRUMP or prepare for the DEATH of everything you love

Subtle, eh? Here’s another example:

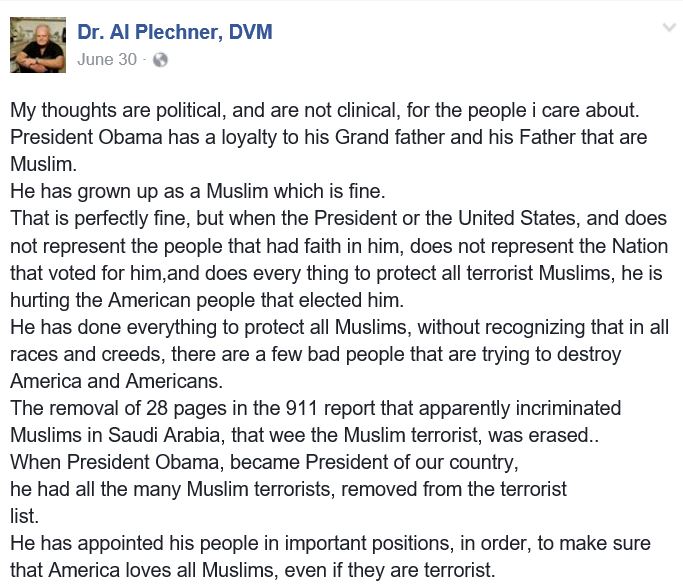

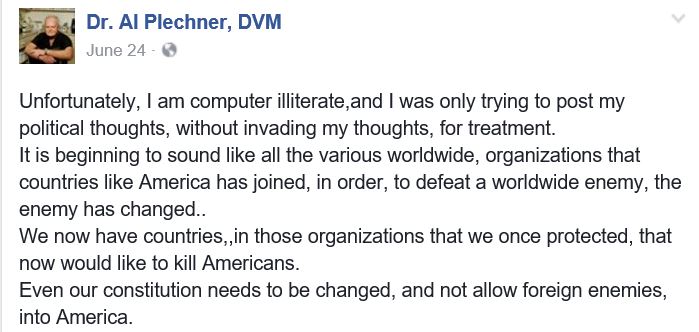

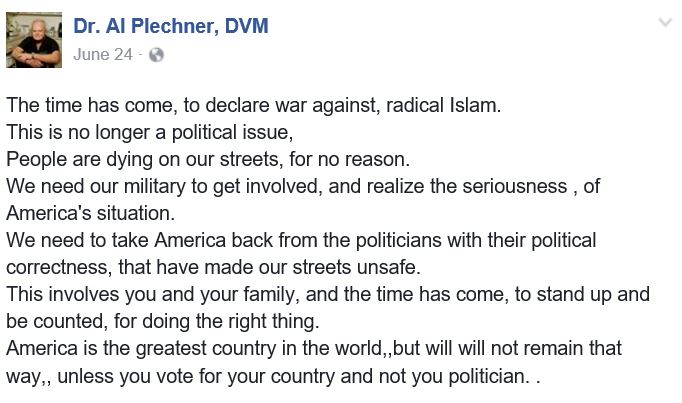

Yup, that’s right. The uber anti-vaxer Andrew Wakefield has been personally assured by Trump that he understands vaccines cause autism. This endorsement has brought along other anti-vaccine loons, including veterinarians like the notorious Patricia Jordan, author of the bizarre extremist screed Vaccinosis-The Mark of the Beast, about whom I’ve written frequently. And another inhabitant of an alternate reality I’ve written about, Dr. Al Plechner (Here and Here), also appears to be a Trump supporter, though for somewhat different reasons. Here are a few snippets from his Facebook page:

Trump has also been quite friendly towards alternative medicine. He has had business interests involving quack urine testing and vitamin and diet schemes. However, this may be more a reflection of his greed and lack of business ethics than a sign of a true ideological commitment to alternative medicine.

Bottom Line

None of the candidates have a spotless record in terms of science policy positions. Politics, values, personal experience, and emotions often trump scientific evidence in the development and defense of beliefs. However, Donald Trump has consistently inhabited an alternate reality and shown flagrant disregard for facts and experts in many areas, and science is no exception. His embrace of anti-vaccine myths, and the support this has generated from the anti-vaxer fringe, as well as his denial of climate change science make him easily the most egregiously and consistently anti-science candidate in the field.