Acupuncture and the Evidence

I have spent several hours, now, listening to lectures discussing scientific evidence and acupuncture. I have also made an effort to find and read many of the specific papers discussed so that I can evaluate their strengths and weaknesses for myself. The instructors for this course have taken a varied and somewhat scattered approach to discussing the scientific evidence, but their presentations seem to fall into three broad categories: discussions of animal model studies investigating the physiologic effects of needling and electrical stimulation of tissues with needles; discussions of the nature of placebo effects; and discussion of the epistemology of science and evidence-based medicine.

The framework for the discussion, of course, begins with the assumption that acupuncture, in some form for at least some conditions, is an effective therapy. This appears to be based predominantly on personal clinical experience. Science is then seen as a means for validating this fact and understanding the mechanisms and application of acupuncture in more detail. The appropriate null hypothesis, that acupuncture has no clinically meaningful beneficial effects, seems to be off the table, which undermines somewhat the instructors’ claims to be approaching this therapy in a truly scientific and evidence-based way. Nevertheless, bias does not itself prove a belief is wrong, only that it may not be based entirely on a rational assessment of the evidence. So I have tried to evaluate the evidence and arguments presented on their own merits.

Pre-clinical Acupuncture Research

This has always been the strongest element in the arguments for acupuncture. There is abundant research evidence that there are physiologic responses to the stimuli generally employed by acupuncturists: dry needling and electrical stimulation via acupuncture needles. And there are plausible mechanisms by which some of these responses could result in clinically meaningful benefits for a number of symptoms. While it remains unclear that any particular needling locations have more or better effects than any other (1, 2), there are undeniably effects to needling and so-called electroacupuncture.

The instructors cite a number of research studies to illustrate specific effects of acupuncture and to at least imply that these represent mechanisms for clinical benefits. Up to this point in the course, these studies are mostly rat models for pain or gastrointestinal motility, and they often focus on the activity or expression of particular neurotransmitters or other neuroactive compounds, ion channels, or other signaling mechanisms within the nervous system. I think the evidence is convincing insofar as needling and electrical stimulation have measurable physiological effects.

However, this is a long way from demonstrating these techniques are effective clinical therapies. Those the effects identified might be mechanisms for clinical benefits, this has to be demonstrated at all levels, from the animal model to the clinical trial, and this has generally not been done. And it is clear that many other stimuli have similar effects. Pinching the skin or needling without penetration or even hitting your thumb with a hammer have measurable effects that could conceivably modify pain, blood pressure, or other variables affected by the nervous system. An effective therapy is not simply any intervention that does something, but an intervention than consistently and reliable does something specific and desirable in a particular patient population. This cannot be proven in lab animal studies, for acupuncture or any other potential therapy.

The studies cited, like all research, have plenty of limitations that have to be acknowledged. Often, there is a lack of blinding or control stimulation, and again the vast majority seem to involve electro-acupuncture, which begs the question of whether needling in predetermined locations traditionally sued by acupuncturists is itself the source of the observed effects, or if electrical stimulation is the treatment actually being studied.

So far, these lectures have added some depth to my understanding of the specific, and quite varied, effects of needling and electrical stimulation, but this is low-level evidence that only supports the claim that acupuncture might be a useful clinical therapy, not the claim that it actually is. That has to be demonstrated by clinical trials.

Clinical Trial Evidence

So what does the clinical trial evidence say about acupuncture. Well, it is a bit tricky. It is difficult to do a well-controlled acupuncture study because it is difficult to effectively employ some of the best methods to control for bias and placebo effects; a placebo control and blinding of patients and therapists to whether placebo of real acupuncture is being used. Patients, especially those with previous experience of acupuncture, can often tell if they are in the treatment or control group, and acupuncturists always know. This makes the results of most trials somewhat unreliable.

There are many, many studies of acupuncture, most of pretty poor quality or high risk for bias. When these are aggregated and assessed for quality in systematic reviews, generally there is no consistent difference between real and sham acupuncture, though both do better in terms of subjective outcomes like pain than no treatment at all or less dramatic ineffective therapies. This evidence is most consistent with acupuncture being mostly a placebo therapy, with perhaps some small effects on pain and other symptoms via non-specific mechanisms.

To their credit, the instructors in this course acknowledge that from an evidence-based perspective, the clinical trial literature does not support much efficacy for acupuncture.

[Acupuncture] activates the brain in areas that are activated when patients take a placebo, thinking it may be a real treatment.

Non-specific effects of needling ANYWHERE activate similar brain regions, but many studies use “non-verum” points as the placebo.

Unsurprisingly, in the vast majority of RCTs studying acupuncture, the treatment is superior to non-treatment, but not superior to placebo.

The most appropriate conclusion to draw from this, using a science-based perspective, would be that acupuncture is likely merely a placebo and does not have predictable, meaningful clinical effects beyond placebo. However, you can imagine the cognitive dissonance accepting such a conclusion would induce in folks not only practicing but teaching acupuncture, and of course the instructors do not come to this conclusion. They appear genuinely committed on some level to the science-based view. However, they also clearly believe acupuncture is effective based on their personal clinical experiences. When the science supports this, they are happy to rely on it. But when the science does not support their experiences, they begin looking for ways to explain the results that do not require giving up their beliefs. Most of the rest of the lectures on evidence for acupuncture consist of this sort of salvage operation, attempting to explain why an effective therapy consistently fails to be validated in clinical trials. This involves redefining placebo effects, challenging the methods of clinical trials, and a lot of goalpost moving.

Placebos

These lectures spend a lot of time discussing the nature of placebo effects, and they make a number of troubling claims about placebos that suggest a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of controlled scientific research. This understanding is most often and articulately represented by the work of Ted Kaptchuk, a proponent of Chinese medicine and a researcher into the nature of placebo effects. Dr. Kaptchuk’s research is interesting, but the conclusions and claims he makes are quite controversial, though they are presented in this course as established science.

One idea that the instructors try to suggest is that placebo effects may not be simply the false perception of improvement in one’s symptoms but real healing.

The meanings and expectations created by the interaction of doctors and patients matter physically, not just subjectively.

This is an idea Ted Kaptchuk has suggested as well, and it is really a rationalization to preserve belief in a therapy that does not outperform placebos in clinical trials. The reason placebos are used, and part of the reason clinical trials have proven so much more effective than individual experience in evaluating medical therapies is that placebos represent a collection of errors that create the impression of improvement without a real, objective change in health.

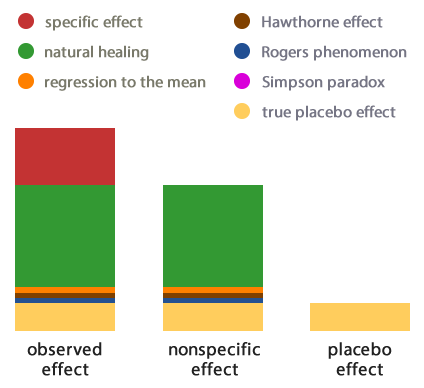

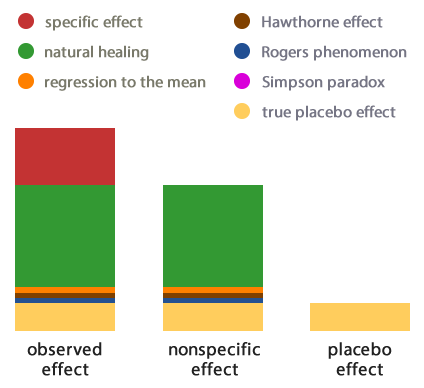

One of the best explanations for what goes into the placebo effects seen in clinical trials comes from Science-based Medicine in a translation of a French article. This graphic illustrates the relationship between research placebos and actual healing.

Many different kinds of error feed into the apparent improvement experienced by patients getting placebos in clinical trials, but these do not represent actual , objective healing caused by the placebo therapy. A number of studies have looked at the question of whether or not placebos have meaningful clinical benefits, as opposed to simply creating the perception of improvement in subjective symptoms while leaving objective measures of health unchanged, and the conclusions do not support the “powerful placebo” idea.

Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, M.D., and Peter C. Gøtzsche, M.D., Is the Placebo Powerless? — An Analysis of Clinical Trials Comparing Placebo with No Treatment. Engl J Med 2001; 344:1594-1602.

Conclusions

We found little evidence in general that placebos had powerful clinical effects. Although placebos had no significant effects on objective or binary outcomes, they had possible small benefits in studies with continuous subjective outcomes and for the treatment of pain. Outside the setting of clinical trials, there is no justification for the use of placebos.

Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2010 Jan 20;(1):CD003974. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3.

Authors’ conclusions:

We did not find that placebo interventions have important clinical effects in general. However, in certain settings placebo interventions can influence patient-reported outcomes, especially pain and nausea, though it is difficult to distinguish patient-reported effects of placebo from biased reporting. The effect on pain varied, even among trials with low risk of bias, from negligible to clinically important. Variations in the effect of placebo were partly explained by variations in how trials were conducted and how patients were informed.

Meta-regression analyses showed that larger effects of placebo interventions were associated with physical placebo interventions (e.g. sham acupuncture), patient-involved outcomes (patient-reported outcomes and observer-reported outcomes involving patient cooperation), small trials, and trials with the explicit purpose of studying placebo. Larger effects of placebo were also found in trials that did not inform patients about the possible placebo intervention.

The literature best supports the traditional idea that placebos fool patients (or, in the case of veterinary medicine, clients and vets) into thinking their condition is improved when it is not by objective measures. Some acupuncture studies illustrate this patter, including one I’ve written about before involving sham acupuncture as a treatment for acute asthma attacks.

Wechsler, ME. Kelley, JM. Ph.D. Boyd, IOE. Dutile,S. Marigowda, G. Kirsch, I. Israel, E. Kaptchuk, TJ. Active albuterol or placebo, sham acupuncture, or no intervention in asthma. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:119-126

In addition to asking the patients how they felt after each treatment, the investigators also measured their lung function, using an instrument that records, among other data, how much air the patients could force out of their lungs in a given period of time. It turns out that this objective measure showed a 20% improvement with the bronchodilator inhaler, but a significantly lower 7% improvement with the inert therapies or no treatment at all. So while the patients couldn’t tell the difference between real and fake therapies, their lungs certainly could.

As David Gorski from Science-based Medicine put it,

[This finding] indicated how dangerous it could be to rely on placebo effects to treat asthma in that it could easily result in the death of your patients by lulling them into a false sense of security of not feeling short of breath when, from a physiologic standpoint, they are on the knife’s edge of respiratory failure.

The instructors refer to this study, but they draw a very different lesson from it than I do. To them, it illustrates the second idea concerning placebos which they suggest might justify acupuncture even if it has no more than a placebo effect, which is that the outcomes of interest ultimately should be the patient experience, not necessarily objective measures of health and disease. As one put it,

A patient centered approach requires that patient-preferred outcomes trump the judgment of the physician.

This strikes me as a dangerous approach to medicine. It is true, of course, that the ultimate goal of medical treatment is the total well-being of the patient. And for humans, at least, the values and goals of the patient are a major determinant of what constitutes well-being. However, there is a reason patients seek the advice and guidance of doctors. Our training and experience gives us a perspective that is different from the patient’s and useful to them. And part of this perspective is an understanding that subjective symptoms are influenced by many factors besides the true trajectory of a disease or overall health. Something can make you feel better without making you truly physically better, and if doctors have methods of assessing this that patients do not have, it is our duty to put this knowledge to the service of the patient’s overall well-being, even if it may sometimes conflict with their short-term perceptions of their symptoms.

In the case of entirely subjective symptoms, of course, the experience of relief is relief, and it cannot reasonably be declared “unreal” without wading into the philosophical morass of qualia, which I try to avoid. However, the experience of symptomatic relief, valuable as it may be in itself, should not be confused with true amelioration of disease or restoration of health. If asthmatics feel temporarily better with placebo therapy, that doesn’t mean we have restored their well-being. Placebo effects, remember, tend to be mild, short-term, and not associated with significant, sustained improvement in health condition.

What the instructors also fail to acknowledge is that placebo effects which lead to subjective experience of relief occur with truly, objectively effective therapies as well as with placebos. We can have both effective treatment and symptomatic relief, and there is no need to settle for only perceived improvement. In fact, I would argue that it is unethical to rely on a placebo therapy to make patients feel better when there are objectively effective therapies available. And when there are not, we are obliged to inform patients of this even if it diminishes our ability to use placebos to relieve their symptoms by fooling them into thinking we have improved their physical health.

Finally, the issue of placebo effects is complicated in veterinary medicine by the fact that some of the effects in the diagram above, those based on belief and expectation, don’t apply to veterinary patients. We can’t fool our pets into feeling better with placebos. However, we can fool their owners and ourselves into believing we have made them feel better when we haven’t. This makes the use of placebos doubly dangerous and unethical in veterinary medicine.

Imperfect Science

The instructors spend some time discussing flaws and sources of bias and error in clinical trials of acupuncture and in the methodology of systematic reviews and meta-analyses used to summarize clinical trial research. The majority of these criticisms are quite valid. There is no question that medical science is, like all human endeavors, deeply flawed and subject to bias and error. I have written about the problematic nature of much research evidence myself, and I actually just completed a master’s thesis specifically looking at some quality measures of veterinary clinical trials, which are far, far from ideal in many ways (hopefully something from this will be published reasonably soon). So questioning the reliability of the scientific literature is fair game, and it is not inconceivable that the benefits of acupuncture could be greater than they appear due to methodological problems with how it is studied.

That said, this begs the question of how else we evaluate therapies like acupuncture. Science is imperfect, but it is far, far superior to any other method we have ever used. The dramatic and unprecedented improvements in human health and longevity that have been brought about by the application of controlled scientific research to health, nutrition, and other related areas, are undeniable. If we must make judgments, and we must make them on the basis of the evidence we have rather than the ideal evidence we would like to have, then what can we rely on that is better than clinical research? While they might not admit it, I suspect deep down the instructors of this course believe their personal experiences are compelling proof that acupuncture is effective, and they find the inability of clinical science to confirm this to be more likely a failing of the research than of acupuncture. The potential bias in this view is obvious. My own view is that we are more likely to come to the right answer more often if we rely on scientific research, flawed as it is, than if we trust out personal experiences.

Bottom Line

The instructors present reasonably good evidence that acupuncture (dry needling and electrical stimulation) have wide-ranging physiologic effects that could plausibly have local and distant clinical benefits. They acknowledge, however, that clinical trials have not tended to support a meaningful, consistent benefit above placebo for acupuncture. Unfortunately, despite their ostensible commitment to evidence-based medicine, they appear to have a strong belief in the efficacy of acupuncture based on their personal experiences, and this has led the to respond to the absence of good clinical trial evidence for the practice by questioning the appropriateness of the methods and outcomes used to obtain this evidence rather than their belief in acupuncture.

The reinterpretation of placebo effects suggested in the course materials, as either true measures of real healing or as sufficient endpoints for therapy in themselves, seem misguided. While symptomatic relief is an important goal for patients, it is not sufficient in itself if it leaves the underlying disease unimproved. And such placebo effects can be obtained as easily by therapies with measurable objective benefits as by placebos. Offering placebos alone is ethically questionable, particularly if patients are misled into believing they are truly effective treatments, and it can harm patients if it creates a false impression of improvement.

The critiques offered of clinical trials and higher level scientific evidence are often valid. But they beg the question of what should be used instead to evaluate therapies such as acupuncture. The implication, that personal experience of success is sufficient reason to utilize a therapy despite an inability to validate its effects through clinical research, seems to suggest that such experiences are as or more reliable than controlled research. The history of science and medicine, and the state of human health, argue strongly against this view.