I recently gave a lecture at the Western Veterinary Conference called “What You Know that Ain’t Necessarily So.” The purpose of this was to take some common or controversial beliefs and practices in veterinary medicine and discuss the scientific evidence pertaining to these. This was not intended as a definitive, “final word” on these subjects, but as an illustration of how weak and problematic the evidence often is even behind widely held beliefs. In some cases, these practices or ideas may actually be valid, but without good quality scientific evidence, we should always be cautious and skeptical about them.

Eventually, I will post recordings of the presentations themselves, but for now I am posting a summary of each topic.

Each starts with a focused clinical question using the PICO format.

P– Patient, Problem Define clearly the patient in terms of signalment, health status, and other factors relevant to the treatment, diagnostic test, or other intervention you are considering. Also clearly and narrowly define the problem and any relevant comorbidities. This is a routine part of good clinical practice and so does not represent “extra work” when employed as part of the EBVM process.

I– Intervention Be specific about what you are considering doing, what test, drug, procedure, or other intervention you need information about.

C– Comparator What might you do instead of the intervention you are considering? Nothing is done in isolation, and the value of most of our interventions can only be measured relative to the alternatives. Always remember that educating the client, rather than selling a product or procedure, should often be considered as an alternative to any intervention you are contemplating.

O– Outcome What is the goal of doing something? What, in particular, does the client wish to accomplish. Being clear and explicit, with yourself and the client, about what you are trying to achieve (cure, extended life, improved performance, decreased discomfort, etc.) is essentially in evidence-based practice.

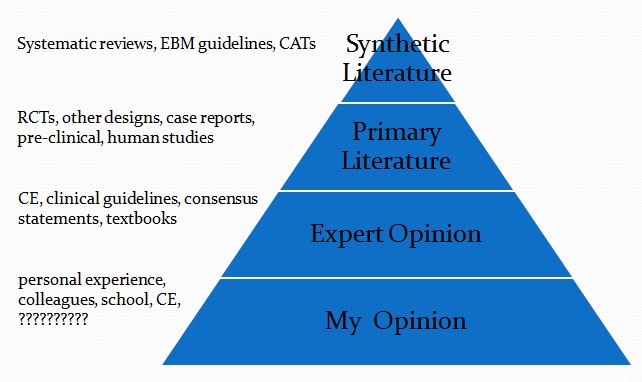

This is then followed by a summary of the evidence available at each of the levels in the following pyramid (which is a pragmatic reinterpretation of the classical pyramid of evidence that is a bit more useful for general practice veterinarians).

Finally, I list the Bottom Line, which is my interpretation of the evidence.

Antibiotics, Endocarditis, & Dentistry

- Clinical question

P- dogs & cats with periodontal disease

I- prophylactic antibiotics with dentistry

C- no antibiotics with dentistry

O- incidence of bacterial endocarditis

2. Synthetic Veterinary Literature

a. No systematic reviews:

b. No critically appraised topics

c. Guidelines-

…use of a systemically administered antibiotic is recommended to reduce bacteremia for animals that are immune compromised, have underlying systemic disease (such as clinically-evident cardiac, hepatic, and renal diseases) and/or when severe oral infection is present.

American Veterinary Dental College

3. Primary Veterinary Literature

Retrospective review of records for ~59,000 dogs with periodontal disease

periodontal disease was associated with cardiovascular-related conditions, such as endocarditis and cardiomyopathy.

- Concerns about diagnostic criteria

- Many data inconsistent with previous findings

- Study design not appropriate to establish causal relationship

Glickman, L.T. (2009)

- Retrospective case (70)/control(80) study

- No association between dental disease or Tx and endocarditis

Peddle, G.D. (2009)

4. Human Literature

a. Systematic Reviews

There remains no evidence about whether antibiotic prophylaxis is effective or ineffective against bacterial endocarditis in people at risk who are about to undergo an invasive dental procedure. It is not clear whether the potential harms and costs of antibiotic administration outweigh any beneficial effect.

Glenny, A.M. (2013)

b. Clinical Practice Guidelines

Today, antibiotics before dental procedures are only recommended for patients…who have:

- A prosthetic heart valve or who have had a heart valve repaired with prosthetic material.

- A history of endocarditis.

- A heart transplant with abnormal heart valve function

- Certain congenital heart defects

American Heart Association

Antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis is not recommended:

- for people undergoing dental procedures

- for people undergoing non-dental procedures at the following sites:

- upper and lower gastrointestinal tract

- genitourinary tract

- upper and lower respiratory tract

Chlorhexidine mouthwash should not be offered as prophylaxis against infective endocarditis to people at risk of infective endocarditis undergoing dental procedures.

National Institute for Health & Care Excellence

Bottom Line

- Endocarditis is rare

- Dental treatment is probably not a major risk factor for endocarditis

- Antibiotics with dentistry are probably not useful in preventing endocarditis

Fun Fact!

- Antibiotics with dentistry are probably not useful in preventing endocarditis

- Overall bacteremia in 6 blood samples-

- Extraction + amoxicillin- 56%

- Extraction + placebo- 80%

- Toothbrushing- 32%

Although amoxicillin has a significant impact on bacteremia resulting from a single-tooth extraction, given the greater frequency for oral hygiene, toothbrushing may be a greater threat for individuals at risk for infective endocarditis.

Lockhart, P.B. (2008)

References

Glenny AM, et al. Antibiotics for the prophylaxis of bacterial endocarditis in dentistry. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Oct 9;10:CD003813.

Lockhart, PB. et al. Bacteremia Associated With Toothbrushing and Dental Extraction. Circulation. 2008; 117: 3118-3125.

Peddle GD, et al. Association of periodontal disease, oral procedures, and other clinical findings with bacterial endocarditis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009 Jan 1;234(1):100-7.

Glickman LT, et al. Evaluation of the risk of endocarditis and other cardiovascular events on the basis of the severity of periodontal disease in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009 Feb 15;234(4):486-94.