Before becoming a veterinarian, I did a master’s degree in animal behavior, working primarily with chimpanzees. These are fascinating creatures, with many of the cognitive abilities of a young human child (and with a similar emotional temperament as well, which can be a problem in an animal far stronger than any human and equipped with large canine teeth!). One of the most interesting observations about chimpanzees in the wild is that they are sometimes seen eating plants, dirt, or other substances not part of their normal diet, substances which are thought to have possible therapeutic values in preventing or treating parasitic infestations, infections, and other medical problems. Other mammals, birds, and even insects have been seen engaging in similar behaviors, and the suggestion has been made that these creatures are, in some sense, deliberately medicating themselves, a phenomenon labeled zoopharmacognosy.

This is, not surprisingly, a popular idea among proponents of herbal medicine and other medical approaches that claim natural remedies and intuitive knowledge are central to health. However, as a skeptic I am well aware of how easily anecdotes, and elaborate theories built on them, can turn out to be descriptions of what we hope or wish to be true rather than of the world as it actually is. Humans are masters of seeing what we want to see and ignoring things that contradict our beliefs. So do animals self-medicate?

How Can We Find Out?

The first question to ask in order to explore this subject is how would we demonstrate self-medication and distinguish it from other behaviors? A variety of criteria have been suggested for identifying self-medication in wild animals. And as always in science a consistent pattern that holds up even when attempts are made to explain it with alternative hypotheses is necessary for a reliable conclusion.

Ideally, animals should be seen to seek out and ingest plants or other substances that are not part of their normal diet. They should do so only when they have some objectively identifiable marker of a specific illness. There should be some plausible explanation for why the substance ingested could potentially affect the illness the animal has (e.g. laboratory evidence that a chemical consistently found in a plant can reduce the levels of a GI parasite; NOT simply an unproven folk belief in the medicinal value of the plant). The marker of illness should consistently resolve after the animal has ingested the substance thought to be therapeutic.

Of course, all of these steps could be present and still not definitively prove self-medication, especially given that most behavior of wild animals isn’t observed, and there are many ways in which observers can skew results be selectively attending to or noting some behaviors more than others. Controlled experimentation would also be needed to rule out other explanations. This is, of course, rarely possible with great apes or other wild mammals, though some work has been done with laboratory animals and insects.

Another question to consider is what mechanism might explain self-medicating behavior if it were observed. Do animals have theories of disease, as humans do, that lead them to select specific therapies based on predictions from these theories? Do they remember or communicate to others the particular remedies for particular illnesses? Such deliberative thinking seems pretty unlikely, and there is no reliable evidence of it, despite extensive research, even in the most cognitively advanced species such as the great apes.

More likely, self-medicating behavior would be, like all other behaviors, a product of natural selection operating on underlying variation between individuals. The tendency to seek out certain tastes or smells, for example, when experiencing certain symptoms could easily be fixed by selection if doing so improved the reproductive success of individuals with genes prompting this behavior over that of individuals without such genes. Of course, such adaptive explanations can easily be manufactured for every behavior, and they need to be demonstrated experimentally when possible to be truly believable.

What’s the Evidence?

Wild Animals

In any case, what is the evidence for self medication? In wild animals, it consists largely of uncontrolled observations with a significant risk of bias or misinterpretation. Anecdotes abound, but rigorous, repeatable patterns with solid links between symptoms, behavior, and outcome have not been demonstrated. It is common to note the consumption of an unusual substance and begin looking for evidence of a medical problem to explain it, but instances of that same problem or consumption of that same substance that are not related are overlooked. This is a form of recall or confirmation bias that makes all anecdotes unreliable as evidence for a particular theory.

The medicinal value of plant ingested in such cases is often assumed based on local folk medicine practices or the presence of certain chemicals in the plant which have in vitro effects that might be relevant. The same sources of evidence are often used to validate all kinds of claims about the medicinal value of herbal remedies, and the reality often turns out to be that there is no such value. These kinds of evidence can only suggest possible relationships, not prove them.

And we have to remember that animals also frequently ingest substances that are actively harmful to them. I pull a surprising variety of potentially deadly objects out of the gastrointestinal tract of dogs and cats on a regular basis. And both domestic and wild animals have been seen to succumb to ingestion of poisons as well as indigestible foreign objects. So any theory about intentional self-medication has to also explain this self-injurious behavior. Are these animals committing suicide? Or, as seems more likely, are they mistaking harmful and inedible substances for food or exploring the world through taste and ingestion without a consistent regard for the likely benefit or harm?

There is, of course, little question that animals seek out specific tastes, smells, and colors in their food that are associated with relevant nutrients. It is reasonable, then, to suppose they might similarly seek out such cues in medicinal substances. And the distinction between food and medicine can be unclear when both are made up of substances found in nature and not processed in any significant way. So, all the anecdotes about self-medication behavior may represent an evolved behavior that reduces the burden of disease and parasitism in some individuals, conferring a selective advantage. As of now, however, this is still simply a hypothesis that has not been rigorously demonstrated.

Laboratory Experiments

More convincing evidence of self-medication is available from experimental studies in insects and laboratory animals. One such study, looking at Monarch butterflies, elegantly shows a facultative change in food source associated with parasitism.

These butterflies normally lay their eggs on milkweed. The larvae ingest the plant and incorporate toxins called pyrrolizidine alkaloids into their tissues. These act as a defense mechanism. Predators eating the distinctively colored butterflies will be nauseated by the toxins and will avoid similarly colored butterflies in the future. This doesn’t, of course, help the individual the predators eat, but it can help related individuals who carry similar genes. This is itself a fascinating and amazing example of natural selection in action.

The research study showed that butterflies affected by a certain parasite preferentially lay their eggs on a variety of milkweed which they do not ordinarily use as a food source. This variety contains a higher level of pyrrolizidine alkaloids than the one they usually lay eggs on. Larvae which hatch out on the more toxic variety and ingest its toxins have lower rates of parasitic infestation and a greater reproductive success than parasitized larvae feeding on regular milkweed.

Interestingly, there is a cost to this behavior. Unparasitized larvae that hatch on the more toxin milkweed actually have a reduced survival, so the behavior is only advantageous in the face of parasitism, otherwise it’s a bad choice for the female butterfly. This is also a nice illustration of the fact that all medical therapies, whether “natural” or not, involve balancing risks and benefits in specific circumstances.

This model shows how behavior that can be called self-medicating can evolve in the same way that food preferences evolve. It also shows that the development of such behavior doesn’t require advanced mental abilities or any mystical intuition about the healing value of plants. The trial-and-error processes of natural selection operating over long periods of time are capable of leading to behaviors that appear purposeful even though they are not.

Bottom Line

So do animals self-medicate? Iwould say the answer is a qualified “yes.”

There is good evidence that some animals have evolved adaptive behaviors which include selecting certain food sources preferentially when the individual has a medical problem that that food source can ameliorate. There is considerably less evidence that animals consistently make accurate choice about ingesting specific substances to treat or prevent specific medical conditions. The numerous anecdotes of behaviors which appear to suggest this could easily be matched by anecdotes of behaviors which are clearly self-injurious or neutral with respect to health, so any theory about self-medication has to account for both kinds of behavior.

The theory that most effectively does so is the same general theory of how natural selection shapes food preferences and other complex behaviors over time, through differential reproductive success among individuals with genes predisposing to different behavior patterns selecting for the most adaptive pattern for the current environment. Many such variations are expressed. Some are harmful or maladaptive and eventually die out, but they can be seen at any given “moment” in evolutionary time and mistaken for something that is adaptive. Some variations may hit upon a truly beneficial behavior and, over time, the genes underlying these behaviors will become more frequent in the population, as wil the behavior.

It is important to point out also that this has nothing to do with the complex theories and mythologies used to justify herbal folk medical practices. People may or may not have gotten the idea of using certain plants for treating disease from watching wild animals. Whether or not this is true doesn’t mean those plants are actually effective as medical therapies, in humans or in animals. That has to be proven in the usual rigorous, controlled, scientific way.

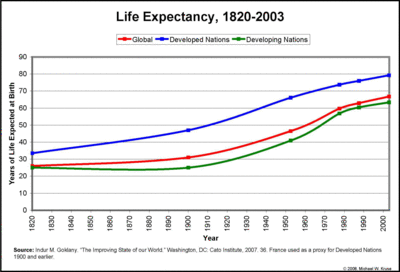

And there is no need to imagine a mystical intuition about the healing power of plants to explain self-medication. Butterflies can be manipulated to show such behavior under controlled conditions, and this can be easily explained by established mechanisms of natural selection, without any need for recourse to mystical explanations. Likewise, the medicinal use of natural substances by animals doesn’t suggest this is a highly effective or desirable form of medicine for modern humans. Evolved self-medication and folk medical practices were part of human behavior for millions of years with little improvement in our overall health and longevity. We are fortunate to have stumbled across methods of identifying cases, treatments, and preventive measures for disease that are far more effective even if not “natural” in any atavistic sense.

There is also ample evidence that animals, including humans, make maladaptive choices about food and medicinal substances. Animals ingest poisons and inedible foreign objects readily. And while humans have a clearly adaptive drive to seek certain nutrients which were scarce in the environment in which we evolved (like sugar, salt, and the ample calories in fat), our inability to curb our desire for these substances now that most of us have an abundance of them is the source of the most serious disease afflicting the developed world. The mechanisms of food selection and self-medication which may be beneficial in one environment, can just as easily be harmful in another. They are not drives towards health and well-being; they are specific behaviors generated by natural selection to better adapt our ancestors to a particular environment.