A client recently asked one of my colleagues for an opinion on an infomercial by Dr. Marty Goldstein for his new commercial raw cat food, Nature’s Feast. There was little new or surprising in this video, but since Dr. Goldstein has a lot of prominence in the media, cat owners may run across this video and be inclined to believe the claims made in it, so I felt it worthwhile to provide some context.

Who is Dr. Marty Goldstein?

I have written a bit about him before as a contributor to the propaganda film The Truth About Pet Cancer, which I havepreviously critiqued in detail.

Dr. Goldstein is another celebrity participant, a veterinarian to the stars. He is also a strong advocate of the bait-and-switch known as “integrative medicine.” This means he will sometimes use science-based treatments, but then often gives the credit for any improvement to homeopathy, acupuncture, raw diets, herbs, and other alternative treatments he also employs.

Dr. Goldstein, much like Jean Dodds, is one of those alternative practitioners who is so nice and caring and respected (at least by celebrity clients and alternative medicine advocates) that it is considered almost taboo to point out that much of what he sells is unproven at best and, in some cases, complete nonsense. His use of homeopathy clearly demonstrates his lack of concern for a science-based approach to medicine, and most of the claims he makes about nutrition are unproven at best or clearly wrong at worst.

He justifies his claims almost entirely with personal anecdotes and beliefs, not with any objective scientific evidence. I have discussed the unreliability of anecdotes many times, as well as many of the flimsy arguments he uses in this infomercial, such as the Appeal to Nature Fallacy, so I will only address them briefly here. Dr. Goldstein is clearly convinced that his personal experience and beliefs are sufficient evidence for rejecting the conclusions of scientific research and nutrition experts, and that alone makes any claim he makes suspect.

The most egregious story he tells is about a dog named Kaiser. Dr. Goldstein convinced this dog’s owners to switch form a commercial to a homemade diet. For a couple of weeks after that, supposedly anybody who touched the dog developed a skin rash, and then the dog’s hair all fell out. Rather than seeing this as a problem or a sign of serious illness, Dr. Goldstein interpreted it as a sign the dog was “detoxing,” releasing harmful chemicals through its skin due to the diet change. Such a dangerously bizarre interpretation of potentially serious symptoms does not suggest a rational or reliable medical judgment.

As for the specific claims he makes in his infomercial, here are a few of the most important.

Grains are Bad for Cats

Grains are popular villains in alternative narratives about nutrition these days. The ratio of the three macronutrients—carbohydrates, fat, and protein— are a key element in the formulation of pet diets. None of these are inherently “good” or “bad,” and while the precise balance among them does have health implications, especially in pets with specific medical conditions, such as diabetes or kidney disease, the idea that commercial diets generally contain “too much sugar” or other carbohydrates and that this causes disease is simply not consistent with the evidence.

Unlike humans, dogs and cats can live with little or no carbohydrate in their diet. However, they can also use this class of macronutrient perfectly well as a source of calories. Some non-digestible carbohydrates (often known as “fiber”) can have beneficial effects on the microbes that live in our pets’ guts, which can influence health, as well as on weight, stool consistency, and other aspects of health. Demonizing an entire class of nutrient is not rational or justified.

As far as the claims that dietary carbohydrates of grains lead to cancer or other disease in pets, these are pure speculation. There are only a few studies looking at diet and cancer risk in dogs and cats, and most of these rely owner recollections for data about diet, which has proven a very unreliable approach in people. There are no studies at all showing restricting dietary carbohydrates reduces the risk of developing cancer in dogs and cats.

There are lab animal studies and epidemiologic research in humans which suggest possible relationships between carbohydrates in the diet and cancer. There are interesting features of the metabolism of cancer cells that suggest diet might have some influence on cancer progression and response to treatment. But there is no real-world, clinical trial evidence that supports the claim that dietary carbohydrates cause cancer in pets or that lower carbs will prevent or help treat cancer.

Carbohydrates are often seen as particularly dangerous to cats, who are truly obligate carnivores and so would naturally eat a high-fat/high-protein diet with few carbohydrates or grains in it, other than those found in the digestive system of herbivorous prey animals. However, research has demonstrated that cats can make use of carbohydrates in food as an energy source, and that these are not a significant risk factor for diabetes or other diseases often blamed on too much carbohydrate in commercial cat food.

Perhaps the pet food ingredients most reviled in criticism of commercial pet foods are corn and wheat. The obsession in popular human nutrition lore about gluten has certainly contributed to this. However, many of the fears about gluten, in human and animal health, are unfounded. People with celiac disease can have negative health effects associated with eating gluten, and there are documented genetic cases of gluten sensitivity in a couple of dog breeds.

However, just as most people are not harmed by eating gluten, there is no evidence that this is a risk factor for disease in dogs and cats. Abandoning wheat as a macronutrient source because of such fears simply leads to the substitution of other sources, and there is no guarantee these are safer or healthier. There is even some evidence that avoiding gluten can cause problems in people who do not have celiac disease.

I have also heard advocates of alternative diets talk about “the menacing power of corn” as if it were inherently poisonous. This is simply silly, and it ignores decades of nutrition research showing the contrary. Like every other food ingredient, corn is not inherently good or bad. It can contribute calories, protein, and essential fats to the diet, and it can be a safe ingredient in a balanced diet for both dogs and cats. It is obviously not appropriate as the sole food source for our pets, but no one is suggesting we use it that way, and claims that pet foods are “mostly corn” are demonstrably untrue.

Artificial Preservatives

This is a claim I have addressed repeatedly in previous articles. A variety of synthetic antioxidants have been used in pet foods over the years to prevent spoilage, and the risk of food poisoning that goes with it. These substances are sometimes feared as potential causes of cancer based on studies in rats or mice where enormous quantities are fed to the animals to evaluate potential risks. However, extensive research on these substances as they are actually used as preservatives in human and pet foods has failed to find such risks in the real world. This is another example of the dangers in putting too much stock in the predictive value of laboratory studies.

Some companies have moved to using “natural” preservatives, such as Vitamin E, and this is what Dr. Goldstein recommends. These may be less effective, and there is no clear evidence that they are safer, but the pet food industry is often forced to respond to the fears of consumers, stoked by claims from proponents of alternative diets, regardless of the evidence for or against the concerns.

Raw Food is Healthier than Cooked Food

This is another claim I have responded to many, many times, and there is still no evidence to support it and plenty of evidence against it. As with most alternative health practices, there are a variety of theories and specific beliefs behind raw feeding, but there are several consistent themes that most proponents of the approach adhere to and use in promoting it.

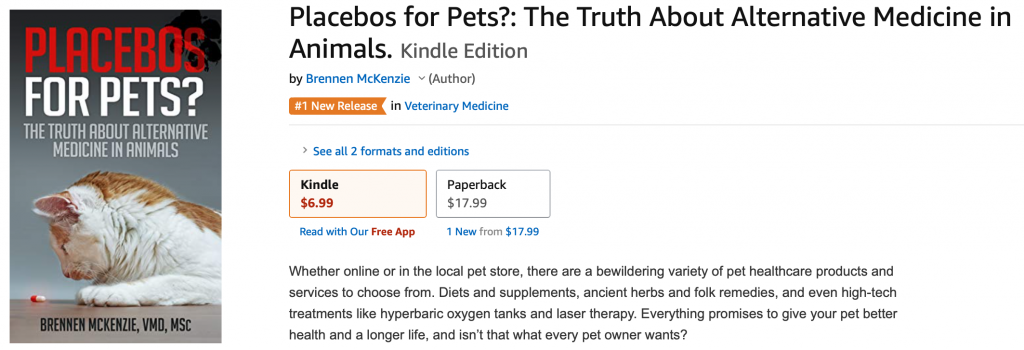

The first is the claim that commercial diets are nutritionally inappropriate and unhealthy. All of the criticisms of conventional diets I have addressed elsewhere on the blog (e.g. 1, 2) and in detail in my book, are put to the service of convincing people raw diets are a better choice. While commercial pet foods are not perfect or without risks, the evidence clearly shows they are healthy and nutritionally appropriate for the vast majority of dogs and cats, and millions of pets live long and healthy lives eating these foods.

The other main theoretical argument for raw diets is our old friend the Appeal to Nature Fallacy. The argument runs something like this: Cats are carnivores and they, or their ancestors, ate whole prey in the wild. Evolution has adapted carnivores to this diet, so it is the optimal diet for them. Our pet cats are essentially the same in their nutritional needs as their wild cousins or ancestors, so a diet as much like raw, whole prey as possible is the healthiest diet for them.

Cats have generally been altered far less by their association with humans than dogs. While dogs are most properly classified as omnivores, or facultative carnivores, cats are true carnivores in terms of their anatomy and physiology. Domestic cats do likely have nutritional needs very similar to wild felines. So does this mean they are better off if fed a raw diet?

Well, the Appeal to Nature Fallacy is a fallacy precisely because what happens in nature doesn’t predict what is good or bad in terms of health. The diet wild animals eat is not the perfect diet designed for their long-term health and happiness, it is simply the diet that is available to them. Evolution works by an impersonal process in which animals do their best to meet their physical needs with what is available in their environment and then reproduce. The individuals who are best at meeting these needs leave more offspring and genes behind, and over time the population comes to be more like the more successful individuals because their genes become more common. Species and their environments are always interacting and changing, and there is never an ideal moment in which a species is optimally suited for its environment and every individual is perfectly happy and healthy.

Animals typically live longer, healthier lives in captivity compared to their wild relatives. Wild carnivores frequently suffer from malnutrition, often starving when they can’t catch sufficient prey to meet their calorie and other needs. They also suffer from parasites, infectious diseases, and injuries from catching and consuming whole prey, and they endure this either suffering or die from it. This is not a perfect, blissful state of nature our pets should aspire to, it is simply the way things are in nature.

Humans no longer live like our stone age ancestors, and we have altered our homes, our clothes, and our diets significantly from that “natural” state. As a result, we suffer less and live longer, healthier lives because of “artificial” practices such as washing and cooking and refrigerating our feed and providing ourselves with nutrients that were once hard to come by. The reduction of scurvy and rickets in modern children compared to those of our ancestors is a good thing, and similarly the reduction in parasites and malnutrition in our pets thanks to “artificial” feeding practices is a positive change.

Raw feeding is often associated with other alternative medicine beliefs and practices. Surveys show that pet owners who feed raw diets are less likely to trust nutrition advice from veterinarians and are also less likely to adhere to other recommendations, such vaccination and parasite prevention, than owners who feed traditional commercial diets. Veterinarians who promote raw feeding and condemn conventional diets are also often suspicious of vaccines and other science-based medical therapies and frequently advocate alternative medical practices. It is not surprising, then, that theories and beliefs which underlie other alternative practices are also found in arguments for raw diets.

None of these theoretical justifications for a raw diet, that commercial diets are unhealthy, that our pets are essentially identical to wild carnivores, that a diet as close as possible to that they would eat in nature is best for their health, or that raw food contains some intangible but essential spiritual nutrient lacking in cooked food, hold up very well to logical scrutiny. So is there any actual evidence that raw diets have health benefits?

A few small and short-term studies have been done in which dogs and cats have been fed raw foods. These show some interesting changes in the bacteria living in the guts of these subjects, in stool, and in metabolism and other variables. However, these studies simply show that some small things change when the diet is changed, not that raw diets have meaningful health effects or that whatever effects are seen are due primarily to the lack of cooking. One study has suggested some possible benefits for dental health in dogs fed a raw diet, but another study identified dental disease and broken teeth caused by such diets.

Overall, there is no convincing research evidence to support the theories and claims for why raw diets should be better for our pets than cooked homemade or conventional commercial diets.

Unlike the benefits of raw diets, which are theoretical and unproven, the risks are well documented. Commercial raw diets which meet industry standards are likely to be nutritionally complete, but many raw advocates feed home-prepared diets, and just like other homemade foods, these diets are frequently nutritionally unbalanced and incomplete. There is even one report of a whole-prey diet (whole ground rabbit) which was studied in cats as a representative of a “natural” diet but which turned out to generate severe heart disease due to taurine deficiency in the cats eating it. So much for “natural” meaning “healthy!”

The most significant risk of raw diets is from food-borne infectious disease. Numerous studies have shown raw diets to be frequently contaminated with potentially dangerous bacteria. While such pathogens can contaminate cooked diets as well, the risk is significantly higher for raw foods. Other studies have shown that animals eating these diets often shed these dangerous organisms in their feces, which exposes humans and other animals to the risk of infection.

Most importantly, serious illness and death in cats and dogs, and in their owners, have been caused by pathogens found in raw pet diets. While the number of confirmed cases of pets and humans suffering or dying from food-borne illness caused by raw diets is small, this is a very serious health hazard. While healthy adult pets may be able to resist these organisms to some extent, there is no absolute immunity in dogs and cats to food-borne illness. Very young, old, and sick animals, and their human caregivers, are at even higher risk.

Dr. Goldstein claims that the freeze-drying of his pet food “completely eliminates” this risk, but that is just his opinion based on anecdote, and this is disputed by both veterinary nutritionists and veterinary infectious disease specialists.

He also claims that cooking destroys nutrients in food, including taurine, which is essential for normal heart health in cats. He claims that the vitamin supplementation done to compensate for this is not effective, but there is ample evidence this is untrue and that supplementation prevents any micronutrient deficiencies in commercial diets. In fact, his claim that cardiomyopathy, or heart muscle disease, is common due to taurine deficiency is completely false. Taurine deficiency can case a disease called dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in cats, but this disease has almost completely disappeared since commercial diets are supplemented with taurine (unlike the cats eating whole rabbit carcasses, who did develop it in one study). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an entirely different heart disease, which is still fairly common, but this is not associated with taurine deficiency, and Dr. Goldstein appears to be mistakenly conflating the two conditions in his ad.

Euthanized Pets in Commercial Pet Food

This is perhaps the most extreme example of efforts to frighten pet owners about commercial diets. Promoters of this story take a few facts and weave them into an unlikely, but shocking narrative. Most countries have pretty strict regulations about the ingredients that can go into commercial pet foods, and these broad rules cover the use of euthanized animals as a food ingredient even if this is not explicitly mentioned in the law. Industry groups, as well as regulators, also have policies prohibiting this practice. Even apart from such rules and policies, though, the claim makes little sense for other reasons.

Food animals, such as cattle, pigs, sheep, and poultry, are the most common and economical source of animal ingredients for pet foods. These are mostly produced in large operations intended to produce food for humans. Apart from being an ethically terrible and unhealthy ingredient for pet foods, euthanized dogs and cats, presumably harvested from animal shelters or picked up by the roadside, would be an unreliable and expensive raw material compared to the ingredients produced by the food animal industry. And, of course, any company caught using dead pets in their pet food would be destroyed by public outrage and likely run out of business. What motivation these companies might have, then, for using such an ingredient is hard to fathom.

There have been several attempts to investigate commercial pet foods and look for evidence of dog or cat DNA, which might suggest there is some truth to this claim. So far, however, none of these investigations have found evidence that cats and dogs have been used as components of pet foods. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for example, found no evidence of dog or cat DNA in pet foods it tested in 2002. While this can’t definitively prove this practice never happens, it is yet another piece of evidence against it.

So how did this idea get started? It’s impossible to know for certain, but the evidence often cited in support of the claim that euthanized pets are used in pet food tends to be open to interpretation, and those inclined to be suspicious of commercial diets and the companies that produce them seem to take the darkest possible view of this evidence.

For example, most of the laws and regulations that would prohibit using euthanized pets in pet food don’t actually address that issue directly. The law doesn’t explicitly prohibit the practice precisely because there’s little evidence it is actually occurring. Instead, the laws prohibit unsanitary and unsafe ingredients, potentially dangerous chemicals such as euthanasia drugs, and other general types of ingredients which would naturally include euthanized dogs and cats. Critics of commercial pet foods tend to claim that because the practice isn’t named in the regulations it must actually be happening, which is not a particularly convincing claim.

Animals euthanized at shelters or killed by cars and not claimed are sometimes disposed of at rendering plants, where the bodies are broken down at high temperature into basic components, such as fats and simple proteins. These components are used in a variety of ways, from fats used as industrial lubricants to proteins being used in shrimp and fish farming. This is considered a more environmentally acceptable means of disposal than burning or burying the remains, but it is understandably disturbing to think about.

Because the parts of food animals not eaten by people are also rendered and are sometimes used in pet foods, there have been concerns that rendering products from euthanized dogs and cats might make their way into pet diets. This is prohibited, again by both regulations and industry policies, and there has not yet been any conclusive evidence that it occurs, but this may be one source of the belief that deceased pets are used as pet food ingredients.

Another, and very serious issue is that the drug pentobarbital, an anesthetic originally used for surgery but now most often used for euthanasia, does sometimes turn up as a contaminate in pet foods. In most of these instances, the amount has been too low to be considered a hazard, but there have been rare cases in which dogs have been sickened and even killed but pentobarbital in canned foods. Investigations into the source of this contamination have typically traced it to the accidental inclusion of euthanized cattle or horses in rendering products intended as pet food ingredients. Once again, no evidence has yet been found showing that euthanized dogs and cats have been the source of pentobarbital contamination of pet foods, but again this may be one source of the belief that this is happening.

Ultimately, like so many of the concerns raised by critics of science-based medicine and conventional nutrition, it is not possible to conclusively prove that the concern is never true under any circumstances. However, the consistent failure to find evidence for the claim despite repeated investigations over decades certainly makes it an unlikely occurrence and not a reason to fear commercial diets or choose untested alternatives with far less evidence for their safety and nutritional value.

Miscellaneous Claims

Dr. Goldstein uses fear to promote his claims. He tells a sad story about the death of one of his cats from urinary tract obstruction, and claims that commercial cat food caused this, but there is little evidence to support such a claim. He also claims that “more cats are getting sick than ever before,” which is the same kind of mythologizing of the “good old days” that alternative vets often peddle to make people fear the health effects of modern life. I have addressed this claim before in regards to cancer in pets, and there is no evidence to support it and some to suggest that our pets, like us, are healthier than in the past.

Dr. Goldstein also argues that cats should be fed organ meats high in Vitamin D partly because they may become deficient from living indoors or in cold climates due to inadequate sun exposure. This is an idea translated directly from human physiology that simply doesn’t apply to cats. While humans make a lot of our Vitamin D in our skin under the influence of sunlight, cats do not, and they always need to get this from dietary sources regardless of lifestyle (e.g. 3, 4). As I have already mentioned, there is plenty of evidence that cooked commercial diets meet this need effectively.

Bottom Line

Dr. Goldstein is basically trying to sell both a product and the ideology behind it in this infomercial. While I have no doubt he is sincere, there is plenty of reason to doubt he is correct. His claims are based on faulty reasoning and anecdote and often contradicted by established scientific knowledge. There are clear risks to raw diets such as Nature’s Feast, and there is yet no real evidence for any of their purported benefits. Advocates of these diets would better serve the pet population by supporting legitimate, rigorous research to show definitively whether their claims are true or not than by inventing and selling products based on gut feelings and anecdotes and ignoring the science and the real nutrition experts.