Categories

- Acupuncture (39)

- Aging Science (35)

- Book Reviews (18)

- Chiropractic (11)

- General (272)

- Guest Posts (6)

- Herbs and Supplements (141)

- Homeopathy (59)

- Humor (42)

- Law, Regulation, and Politics (68)

- Miscellaneous CAVM (32)

- Nutrition (74)

- Presentations, Lectures, Publications & Interviews (73)

- Science-Based Veterinary Medicine (122)

- SkeptVet TV (9)

- TikTok (7)

- Topic-Based Summaries (11)

- Vaccines (30)

A Book from the SkeptVet

Please follow & like us :)

Evidence Update and Review for Yunnan Baiyao

Introduction

In 2010 I first evaluated the Chinese herbal remedy known as Yunnan Baiyao, and I have reviewed additional evidence repeatedly since (1, 2, 3). So far, I have found little reason to believe claims that this remedy can stop bleeding in veterinary patients.

The ingredients are poorly described and not regulated or standardized, as is always the case with Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) remedies, and it is unclear if they have all been disclosed since the recipe is consider a commercial secret. TCM remedies have frequently been found to contain toxins and unreported pharmaceuticals, and some YB tested has been found to contain low levels of toxic substances. The TCM theory for how it works, involving movement of blood and mystical and ill-defined entities such as Qi, is inconsistent with established scientific understanding of physiology and blood clotting mechanisms. There are a number of more scientific theories for how the many chemicals in the product might affect bleeding, but none have been properly validated, and it is recommended primarily on the basis of tradition and anecdote.

Of course, despite the implausibility and lack of a clear mechanism, some clinical research has been done. In humans, the most recent review (from a source known to be biased in favor of TCM treatments, c.f. 3, 4) found some evidence of effect but also found that 1) most of the published research was of low quality and high risk of bias, 2) for some conditions the apparent effect disappears when lower quality studies are excluded, and 3) there is evidence of publication bias, in which negative studies remain unpublished creating an inaccurate impression of the true state of the evidence.

Such weak evidence might justify further research, ideally beginning with full identification of components, basic physiologic and pharmacologic studies, and then progressing through pre-clinical studies before clinical trials, as is the appropriate and expected course of investigating new medications. However, the current evidence does not really justify routine clinical use.

There is also some research into Yunnan Baiyao in veterinary species, and I have reviewed this in my previous posts. A couple of new small studies were recently presented at the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) annual forum, so I thought it would be worth reviewing those and summarizing the evidence to date.

Recent Studies

MacRae R. Carr A. The Effect of Yunnan Baiyao on the Kinetics of Hemostasis in Healthy Dogs. ACVIM Forum, National Harbor, MD, 2017.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the effect, if any, of Yunnan Baiyao on laboratory measures of blood clotting and to look for any obvious, short-term adverse effects. Six laboratory dogs were given the product once a day for six days and clotting measures compared before and during the treatment. No harmful effects were reported, and there was no change in any measure of blood clotting.

Adelman L. Olin S. Egger CM. Stokes JE. Effect of Oral Yunnan Baiyao on Periprocedural Hemorrhage and Coagulation in Dogs Undergoing Nasal Biopsy. ACVIM Forum, National Harbor, MD, 2017.

The abstract begins with the statement, “The hemostatic efficacy and safety of Yunnan baiyao (YB) has been demonstrated across multiple species.” This isn’t actually accurate, and it reveals a pretty clear bias on the part of the investigators, which is relevant when looking at the methods and conclusions of the study.

Nineteen dogs having nasal biopsies were randomized to Yunnan baiyao or placebo before having nasal biopsies taken, which commonly causes some bleeding. A variety of outcome measures were evaluated, including laboratory values associated with clotting and assessments of how much blood was lost and how long it took the dogs to clot after biopsy. The report indicates appropriate blinding of investigators, caretakers, and statisticians. However, not all dogs were assessed with the same measures, which introduces some inconsistency and variability into the results.

Time for bleeding to stop- Exactly how this was measured is not described. The YB group ha d a slightly shorter BMBT (300+/- 12 seconds vs 367+/- 9 seconds). Several other variables (age, history of nosebleeds, blood pressure, and number of biopsies taken) were also associated with the BMBT, though the details were not reported.

BMBT (time for bleeding to stop from a standardized cut on the gums)- There was no difference between the groups.

TEG (a lab measure of clotting)- There was no difference between the groups.

Total blood loss- It is also not clear how this was measured. There was no difference between the groups.

Despite the failure to find an effect for most measures and the questionable clinical significance of the one difference seen (a difference from 46 to 88 seconds in the time for bleeding to stop), the authors naturally conclude that the study supports using YB routinely before this type of procedure.

Veterinary Evidence Summary

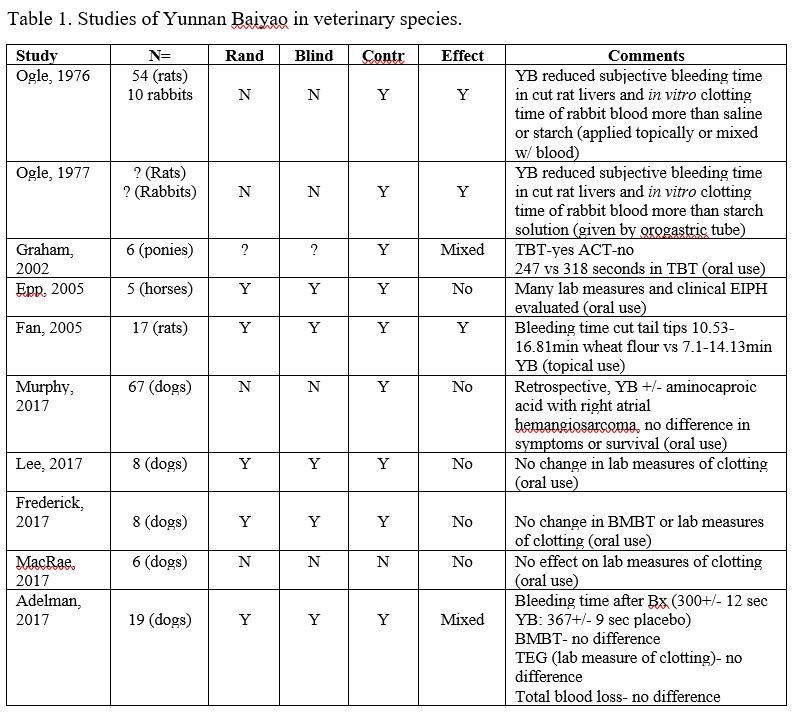

The table below lists all of the actual in vivo studies in veterinary species I have found. It also lists some key features of these studies that help evaluate how reliable their results are, including the number of animals studied, the use of key methods for preventing bias, such as randomization, blinding, and a control group, and the outcomes.

Table 1. Studies of Yunnan Baiyao in veterinary species.

Of these ten studies, 5 found no effect at all, and 2 others showed mixed results, with possible effects in some measures evaluated in the studies but not in others. Of the three fully positive studies, two did not report any of the major methods for controlling for possible bias and other sources of error.

Overall, this is a very unconvincing set of data. Even clearly ineffective methods can have some positive studies due to bias and error alone, so the lack of a clear, consistent pattern of expected effects is troubling. Not all of the studies used the same measures, so it is possible the product could have some clinical effects by some mechanism that doesn’t affect the laboratory measures of clotting usually used, but that is a big stretch.

It is also worth noting that the studies showing some effect didn’t look find any benefit in terms of clinically important outcomes, such as survival, need for transfusion, etc. Even under the most optimistic assessment of the evidence, it may be that Yunnan Baiyao speeds clotting in the case of small wounds by a few minutes, but this may not necessarily have any meaningful benefit for actual patients.

Bottom Line

The TCM rationale for using Yunnan Baiyao is part of an unscientific, quasi-religious belief system and cannot be accepted as a sufficient basis for using an otherwise unproven remedy on patients, especially when the ingredients in that remedy are not fully disclosed or regulated for quality, consistency, and safety. The more plausible scientific hypotheses for how Yunnan Baiyao might work remain unproven.

The clinical research evidence is mostly negative, and even positive studies have not shown any significant effects on clinically meaningful objective outcomes. No clear evidence of harm has yet been found, though the limited nature of the evidence does not ensure that the product is truly safe.

References

Ogle CW, Soter D, Cho CH (1977) The haemostatic effects of orally administered yunnan bai yao in rats and rabbits. Comparative Medicine East and West 5:2, 155-160

Ogle CW, Dai S, Ma JC. The haemostatic effects of the Chinese herbal drug Yunnan bai yao: A pilot study. Am J Chin Med (Gard City N Y) 1976;4:147–152.

Graham L, Farnsworth K, Cary J (2002) The effect of yunnan baiyao on the template bleeding times and activated clotting times in healthy ponies under halothane anesthesia. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 12:4; 279; 2002 (abstract only)

Epp TS, McDonough P, Padilla DJ, et al. The effect of herbal supplementation on the severity of exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage. Equine and Comparative Exercise Physiology 2005;2:17-25.

Fan C, Song J, White CM. A comparison of the hemostatic effects of notoginseng and yun nan baiyao to placebo control. J Herb Pharmacother 2005;5:1–5

Murphy LA, Panek CM, Bianco D, Nakamura RK. Use of Yunnan Baiyao and epsilon aminocaproic acid in dogs with right atrial masses and pericardial effusion. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2016 Sep 26. doi: 10.1111/vec.12529. [Epub ahead of print]

Frederick J, Boysen S, Wagg C, Chalhoub S. The effects of oral administration of Yunnan Baiyao on blood coagulation in beagle dogs as measured by kaolin-activated thromboelastography and buccal mucosal bleeding times. Can J Vet Res. 2017 Jan;81(1):41-45.

Lee A. Boysen SR. Sanderson J. et al. Effects of Yunnan Baiyao on blood coagulation parameters in beagles measured using kaolin activated thromboelastography and more traditional methods. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine. 2017;5(1):53–56.

MacRae R. Carr A. The Effect of Yunnan Baiyao on the Kinetics of Hemostasis in Healthy Dogs. ACVIM Forum, National Harbor, MD, 2017.

Adelman L. Olin S. Egger CM. Stokes JE. Effect of Oral Yunnan Baiyao on Periprocedural Hemorrhage and Coagulation in Dogs Undergoing Nasal Biopsy. ACVIM Forum, National Harbor, MD, 2017.

Posted in Herbs and Supplements

26 Comments

Evidence Update: Vaccination and Autoimmune Disease

One of the potential adverse effects of vaccination is the triggering of autoimmune diseases in susceptible individuals. There is some evidence in humans, for example, that the routine MMR vaccine (which prevents measles, mumps, and rubella) can trigger an autoimmine disease, called ITP, which destroys platelets and reduces a patient’s ability to form normal blood clots. The evidence suggests this occurs in roughly 1-3 children for every 100,000 MMR vaccinations.

While this is a real and serious risk, it is important to note that not only are the diseases prevented by this vaccine a much greater risk, but it turns out that these disease can also cause ITP and at a much higher rate than the vaccine (1 child out of every 3,000-6,000 cases). Therefore, the benefit of vaccination is clearly greater than the risk in this case.

There is, as always, far less data to determine what, if any, risk of autoimmune disease there is in vaccination of dogs and cats. Both ITP and IMHA, another autoimmune disease involving destruction of red blood cells, occur in dogs, and these have been reported to follow vaccination. However, the relevant research literature is sparse, flawed, and inconsistent. The bottom line from my previous review of the literature was this:

Bottom Line

- Little evidence vaccination causes IMHA/ITP

- No consistent temporal association

- Data are weak

- Overwhelming majority of vaccinated animals do not develop these diseases

- Infection can be a greater risk for IMHA/ITP than vaccination

- Don’t vaccinate more than necessary

- Don’t vaccinate less than necessary

- Don’t avoid vaccination out of fear of IMHA/ITP

A small piece of additional evidence was recently presented at the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) 2017 Forum.

Moon, AKB. Veir, J. Vaccination Behavior and Adverse Events in Dogs Treated for Primary Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia (Abstract HM17) ACVIM Forum, National Harbor, MD, 2017.

This study surveyed the owners and veterinarians of dogs who had been diagnosed with IMHA. Such dogs are frequently not vaccinated once they recover from the disease because of concerns that vaccination might trigger a relapse. This is often done even when there is no specific reason to think vaccination triggered the initial episode. It is a reasonable precaution, but since it is not clear that vaccination actually is a risk factor for ITP or IMHA, it is possible that these dogs are being left vulnerable to infectious diseases unnecessarily.

In this small study, survey results were available for 44 dogs. There were several relevant findings:

- The average time from most recent vaccination to the initial onset of IMHA was 351 days. Such a long period makes it unlikely that vaccination was a major trigger for IMHA in many of these dogs. It still might have been in the subset who were vaccinated closer in time to the onset of their illness. This study found no such temporal relationship, but a different study design would be necesary to confirm that.Previous studies have found only a small proportion of IMHA cases received vaccinations in the 2-4 weeks before the onset of their illness, and most found no difference in recent vaccination rates between dogs who developed these diseases and comparison dogs who did not. So far, the overall data suggests that vaccination is rarely a proximal trigger for these autoimmune disease, though whether they play a role as an overall risk factor isn’t known.

- About half of the dogs had not been vaccinated since their IMHA diagnosis. This is consistent with the common practice of many vets to eschew vaccination in dogs who have had a history of autoimmune disease. However, about half of these dogs did receive vaccines after their diagnosis, and almost all of these were rabies vaccines. This is likely because rabies vaccination is legally required in most of the U.S. and exceptions are not always allowed for dogs with a history of autoimmune disease.Only 2 of the 21 dogs who were vaccinated following their IMHA had any reported adverse reaction. These two reactions were typical of the acute hypersensitivity reaction seen with vaccination. No relapse of IMHA or other autoimmune disease was reported in the vaccinated dogs. This suggests that such dogs may not be more sensitive to vaccination than other dogs, though again the size and methodology of this study is not adequate to demonstrate that with any certainty.

- Though this is just a small bit of data, it does fit into the larger context of existing evidence in dogs, and the much more comprehensive evidence in humans, suggesting that vaccines play an extremely small role, if any, in triggering such autoimmune diseases, While caution is warranted, and certainly unnecessary vaccination should be avoided on principle, there is no justification for extreme and confident claims that vaccines are a major cause of these autoimmune diseases in our pets or that what risk may exist outweighs the benefits of appropriate vaccination.

Posted in Vaccines

78 Comments

Canine Influenza Update

In 2015, I wrote about the first canine influenza (CI) outbreak in the United States, in the Chicago area. At the time, I emphasized a few key facts about this disease, which I will review here:

- CI is a highly contagious viral disease which causes upper respiratory symptoms (cough, sneezing, nasal discharge, etc.). Symptoms range from mild to serious, though the diseases is rarely fatal and many dogs do not require medical treatment.

- There are two varieties of CI, H3N2 and H3N8. Neither can infect humans.

- There are several vaccines available to protect against CI. Some are specific to one strain, others can provide some protection against both strains. There is some evidence to support safety and efficacy for these vaccines, however the information available is limited. Some have been conditionally licensed, meaning that they have been approved with less than the usual required research evidence in order to allow a faster response to the threat of CI outbreaks. Whether or not a dog should be vaccinated, and with which vaccine, depends on the risk of exposure, the health of the dog, and a variety of individual factors that should be discussed with your veterinarian. There is no evidence to support claims sometimes made by anti-vaccine activists of serious harm or lack of efficacy for these vaccines.

- There is also no evidence to support claims that alternative methods, such as homeopathy, nutritional strategies, herbs or supplements, or other methods are effective in preventing or treating CI. Some, such as homeopathy, clearly are not effective. Others have not been properly tested.

A number of CI cases have been confirmed recently in Florida, which has renewed concern, and media coverage, regarding this disease. This, inevitably, has led to increased exposure for proponents of pseudoscientific and anti-science perspectives. Fortunately, there are a number of reliable sources of information about canine influenza that I encourage dog owners to make use of:

American Veterinary Medical Association

University of Florida School of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

Unfortunately, because CI occurs in outbreaks it is the sort of disease that encourages hysteria and panic. This tends to lead to a proliferation of misinformation about the disease itself and about prevention and treatment. The usual opponents of science-based medicine and vaccination tend to come out of the woodwork to oppose or denigrate legitimate prevention and treatment methods and to promote unscientific or untested alternatives. The mainstream media is often unable to distinguish between legitimate expertise and ill-informed passion on medical topics, and so advocates of pseudoscience often get opportunities to spread their misinformation.

This morning, for example, a report on CI was broadcast on the popular CBS Morning News program. In a classic example of false balance, the reporter interviewed not only veterinary medical personnel and experts at the University of Florida but also an anti-vaccine activist from one of the most extreme and unreliable sources of veterinary medical misinformation available, Dogs Naturally magazine. This kind of uncritical reporting of medical issues misleads viewers and supports claims and fears that have no legitimate scientific basis.

I have contacted the network and the reporter involved to point out the danger of this kind of false balance in medical reporting. Public response to such reporting has been very successful in improving coverage of some scientific issues, such as climate change, so I encourage anyone interested in fact-based public debate about science to watch for this issue and contact local and media and journalists to call attention to it whenever possible. Here, for example, is the response I provided to the CBS Morning News:

I was deeply disappointed with this report on canine influenza. In the course of this report, you interviewed Dana Scott of Dogs Naturally magazine, who suggested that vaccination for canine influenza was unnecessary and driven by profit rather than medical considerations. Ms. Scott has no medical or scientific qualifications or expertise. The web site and magazine she is affiliated with promote extreme anti-science positions and medical quackery that endangers the health of veterinary patients.

Hopefully, you would not interview an astrologer to “balance” the opinions of an astrophysicist like Neil Degrasse Tyson. I presume you would also not solicit the views of proponent of witchcraft or faith healing to balance the views of your own medical correspondents. Interviewing Ms. Scott and promoting her extremist and unscientific views is equally irresponsible and a disservice to your viewers, who may be misled into believing her views have some scientific legitimacy.

The decision whether or not to vaccinate for canine influenza and which vaccine to use should be based on exposure risk and scientific evidence regarding the relative risks and benefits of vaccination. The irrational and unsupported views of anti-vaccine activists should have no role in such a decision.

As a regular viewer of your program, I am now obliged to question the validity of your reporting on other areas in which I do not have expertise since you have failed so dramatically to present accurate information on a subject about which I am familiar. I hope you will take responsibility for this mistake and clearly remind your viewers that the consensus among experts and scientists is not consistent with the unsupported and extremist views of Ms. Scott.

Posted in General

29 Comments

Evidence Update- PBDE Flame Retardants and Hyperthyroidism in Cats

A couple of years ago, I wrote about the proposed connection between a collection of once-common flame retardant chemicals (PBDEs) and hyperthyroidism in cats. While the notion of “toxins” as the cause of disease is often a vague and ill-founded idea promoted by advocates of alternative medicine, there are certainly some environmental toxins that clearly cause disease, and it is important that we be vigilant in evaluating and eliminating these. The case for PBDEs as the cause of hyperthyroidism rests primarily on three points:

- PBDEs came into common use at about the same general time as hyperthyroidism, once unheard of in cats, became a relatively common disease.

- There are laboratory studies supporting the potential influence of PBDEs on the thyroid hormone system in multiple species.

- There are some associations between PBDE levels and the occurrence of thyroid disease in cats, though not all studies consistently show this.

The hypothesis that PBDEs may play a causal role in feline hyperthyroidism is plausible and supported by some evidence, though there are also other hypotheses with similar support, and it seems likely that multiple causal factors are involved.

The subject has gotten a lot of attention recently due to an article in the New York Times which discusses the problem of hyperthyroidism in cats and the possible role of PBDEs. The article is pretty reasonable and balanced in its discussion of the subject, but it is easy to miss the nuance and take away the message that PBDEs are definitely the major culprit in this disease.

Given the renewed interest in the subject generated by this article, I thought I’d take another look at the literature and see if there was any new evidence on the subject. I found a nice study from 2016 which certainly doesn’t solve the question once and for all but which does add some additional information.

Guo WeiHong; Gardner, S.; Yen, S.; Petreas, M.; Park JuneSoo. Temporal changes of PBDE levels in California house cats and a link to cat hyperthyroidism. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50, 3, pp 1510-1518

This study looked at a relative small number of cats (22 total: 11 each with and without hyperthyroidism). The investigators measured PBDE levels, as well as levels of several other environmental toxins as a control, and compared the levels between cats with thyroid disease and those without as well as between two time periods: 2008-2010 and 2012-2013. This latter comparison was done to evaluate changes in PBDE levels over time. These compounds were banned in 2004, and PBDE levels have been declining in humans as a result, so the hope was they would be declining in cats as well.

The results did, encouragingly, show that PBDE levels have been declining, though cats still have much higher levels than humans (probably because they are more likely to ingest dust from the environment, in the process of grooming themselves). They did also find higher levels in cats with thyroid disease than in those without, which might support the idea that PBDEs are part of the cause of this condition. However, they also found higher levels of the unrelated environmental toxins in hyperthyroid cats compared with normal cats. One of the features of hyperthyroidism is that cats lose weight quickly. This weight loss can lead to an increase in blood levels of many compounds since the same amount of the substances are present in a now smaller cat. Therefore, it isn’t entirely clear if the higher PBDE levels in hyperthyroid cats reflect its role in causing the disease or simply the fact that these cats have lost weight rapidly while the healthy cats have not.

The bottom line form this study is that, as in the past, there appears to be some association between PBDEs and hyperthyroidism in cats, but it is not as simple as saying PBDEs are the sole cause of the condition. It is also encouraging that PBDE levels appear to be declining in cats, as in humans, due to the gradual elimination of PBDE use following the 2004 ban. If PBDEs are, in fact, an important factor in causing hyperthyroidism, we should expect the incidence of this disease to decline as a result. If the incidence does not decline, then we will have to keep looking for other risk factors.

Posted in General

5 Comments

Chinese Herb vs Metronidazole for Diarrhea in Dogs: An Example of the Problems with Alternative Medicine Research

Not everything that looks like science really is science. I’ve written about the faux science of some alternative medicine publications, such as the Integrative Veterinary Care Journal, which often publish articles that are held up as scientific evidence for alternative theories but which don’t qualify in any way as scientifically legitimate. And not all science is good science or reliable as evidence. This is, sadly, true of much of the veterinary literature, conventional or alternative. However, alternative medicine publications are particularly vulnerable to poor methodology and creating the appearance of reliable scientific evidence without the substance. A close reading of the literature cited by alternative practitioners to support their claims often finds that the evidence is unreliable or doesn’t actually say what they claim it does (e.g. The Evidence for Homeopathy: A Close Look).

So-called Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) (which is, arguably, not traditional at all), is a particularly clear example of this problem. There is an abundance of published research on TCM therapies, especially acupuncture. Most of this is published in China or in TCM-dedicated journals, and it almost always finds exactly what the investigators hope and expect to find. When almost every single research study reports positive results, and when most contain few effective controls for bias, the odds are good that the literature represents the strength of belief among TCM proponents more than the objective truth about the method.

A recent article from the American Journal of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (AJTCVM) illustrates this problem quite well:

Fowler MP. Deng-Shan S. Huisheng X. A Randomized Controlled Study Comparing Da Xiang Lian Wan to Metronidazole in the Treatment of Stress Colitis in Shelter/Rescued Dogs. AJTCVM. April, 2017.

The AJTCVM is usually not available except to members of the TCVM organization that publishes it, but this article was recently made public. This may be related to the ongoing efforts of the TCVM community to gain recognition for herbal medicine as a board-certified veterinary specialty, but this is just speculation.

This study compares a TCVM herbal remedy to a pharmaceutical for “stress colitis.” The structure of the experiment has many of the hallmarks of traditional scientific clinical research. Unfortunately, the work as a whole does not support the authors inevitable conclusion that the Chines herb is an effective treatment. I will summarize briefly the main problems with the study.

What is “Stress Colitis?”

Unfortunately, this is a commonly used term that does not have a meaningful definition based on established pathophysiology or research evidence. Dogs often develop acute large-bowel diarrhea, with the sort of symptoms described by the authors of this study. This is associated with many possible causes, from parasites to eating unfamiliar or unwholesome substances to changes in routine that are likely a source of psychological and physiological stress. Unfortunately, the term stress colitis is a vague one that can be applied to any acute large bowel diarrhea when no specific cause has been sought or found. In this study, the authors ruled out some common parasites as the cause of diarrhea, but no actual cause was identified. Therefore, the entity they are testing treatments for is ill-defined and could easily be a hodgepodge of different causes.

This wouldn’t be a fatal weakness in itself, so long as objective and consistent criteria were used to identify the problem. However, the criteria for including and excluding patients and for determining whether or not they responded to treatment were subjective and vague as well. This leaves it entirely to the judgement of the investigators whether the dogs had “stress colitis” or not, and whether they got better or didn’t get better with treatment. Such a source of bias is a serious flaw, especially given the lack of any blinding, as I will discuss shortly.

Metronidazole

The authors designed the study to compare the herbal product to metronidazole, a drug commonly used to treat all sorts of diarrhea, including whatever people choose to label “stress colitis.” Unfortunately, there is no scientific evidence showing that this drug is actually effective for acute large bowel diarrhea from most causes, including cases for which no specific cause can be identified. The authors claim the drug is recommended in a commonly used drug handbook, but this is not correct. All the scientific evidence for the use of metronidazole in treating colitis involves chronic, not acute cases, and mostly diseases with an established cause, such as ulcerative colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and giardia. In other words, the authors cite evidence regarding chronic large bowel diarrhea due to a variety of different causes as evidence for using metronidazole as a treatment for acute large bowel diarrhea of unknown cause (presumed to be related to stress). This misrepresents the evidence.

Metronidazole as a treatment for acute idiopathic large bowel diarrhea is common, but that is an entirely anecdotal practice for which there is no specific scientific support. This means the owners are comparing an untested herb supported only by anecdotal evidence against an untested medication supported only by anecdotal evidence. Not a very robust study for determining the real safety and efficacy of either treatment.

The authors also seem quite ambivalent about metronidazole. On the one hand, they want to identify it as a treatment proven to be effective for stress colitis so they can claim their herbal remedy is effective if it seems to work as well. They state that metronidazole is “typically effective” and is “the drug of choice” for stress colitis. Since the diseases is not clearly defined or understood and the drug actually isn’t proven to be an effective treatment for it (though it is widely used in this way), the implication here is false.

On the other hand, the authors clearly want to emphasize the dangers of conventional therapy so they can make the common claim that their alternative therapy is safer. So only a few sentences after claiming metronidazole is typically effective, they refer to the “poor clinical response” and “ineffectiveness” in some dogs, while then providing a scary list of potential side effects with no discussion of how frequently these actually occur or their relationship to dose or other factors.

Metronidazole does, of course, have risks that have been established by scientific research, as does any treatment with any real effects at all. Nothing works without some risk of unintended effects. However, the risks are generally seen with high doses and long-term use. And while the authors identify no known side effects for their herbal remedy, this is simply because there is virtually no research on this product, and no previous clinical studies at all in dogs. It might be safer or mare risky than metronidazole, but without appropriate research we can’t know. In this study, at least, there were no apparent significant adverse effects. One dog in each group was reported to have vomiting, but whether this was related to treatment is unclear, and there was no difference between the groups and no other possible adverse reactions noted.

Study Design Problems

This study is a classic example of how to set up a study to show what you already believe and want to show. The first author specifically says in the paper that she wanted to run the study because she believes the herb is effective, and may work better than metronidazole, based on her clinical experience. This bias can freely influence the results because there is almost no control for bias in the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were subjective, the response to treatment was subjectively measured, and no one was blinded to the group assignment or treatment of any of the dogs. These are not pedantic details but the fundamental core of good, objective science that is absent from this study.

The results of the study seem, not surprisingly, to support the beliefs of the authors. There was no difference in the resolution of diarrhea between the two groups. More than 85% of dogs in both groups got better within 10 days, and the average time to resolution of diarrhea was nearly identical at about 3 ½ days. The authors claim this shows the herb to be just as effective as metronidazole. However, remember that metronidazole has never been actually tested for treating acute large bowel diarrhea, so we don’t actually know if it is effective. What we do know is that in almost every study of acute diarrhea in dogs, most of the dogs get better no matter what we do. Several other studies have shown that more than 80% of dogs with acute diarrhea get better within 3-5 days, just as in this case, with all sorts of other treatments besides metronidazole and the herb used in this study ( e.g. 1, 2). It is very likely that most of the dogs in this study got better regardless of treatment and would have with neither metronidazole nor the herb. The absence of a placebo or no-treatment control group is a serious flaw that makes it impossible for the authors to address this very significant potential explanation for their results.

TCVM Nonsense

It is also important to remember the concept of Tooth Fairy Science. You can design a scientific study to see whether the Tooth Fairy pays out more money depending on the type of tooth lost, the age or sex of the child, and many other variables. You can even do all sorts of fancy statistics to evaluate the results. However, none of this means anything if, as is likely, the Tooth Fairy does not exist.

TCVM is a great example of Tooth Fairy Science. The herb in this study is supposed to be appropriate for cases with “excess pattern of large intestine damp heat” because is can “clear damp heat,” “move Qi,” and “warm middle Jiao.” Since all of the folk mythology of TCVM theory is implausible, untestable, mystical nonsense, the results of controlled studies of it are meaningless. That is not to say the herbs used in TCVM might not have real, and useful biological effects. But these need to be determined by real science, evaluating the chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmacology of these herbs in patients with scientifically defined diseases and measured using appropriate scientific methods. None of this is part of this paper.

The authors suggest that the herb they test has been shown to have benefits for diarrhea, though it has not been clinically tested in dogs before. However, the literature they cite shows only a handful of lab animal studies, which don’t look at anything like acute idiopathic large bowel diarrhea, and a couple of weak studies in humans for, again, quite different problems such as chronic ulcerative colitis. The reality is that despite the attempt to recreate the trappings of science, the authors are basing this study on the pseudoscientific nonsense of TCVM theory, their own personal beliefs and experiences, and anecdotal evidence, not a plausible scientific rationale demonstrated through real research. Tooth Fairy science at its finest.

Bottom Line

This paper illustrates the deep problems in the research literature associated with much of alternative medicine, including TCVM. Implausible therapies are selected according to mystical, pseudoscientific theories and anecdote and then tested inappropriately with little or no serious attempt to control for bias and error, and then the results are overinterpreted to suggest equivalence to conventional treatment or even the superiority of the alternative methods. The body of sloppy and unreliable literature that results misleads not only the public but veterinarians and other scientists into believing there is real reason to take these therapies serious.

This, in turn, supports the deceptive Trojan Horse of integrative medicine, which seeks to blur the real and important distinction between science-based medicine and alternative medicine. Real scientific evaluation of many alternative therapies, especially herbal remedies, needs to be done. This ain’t it. Unfortunately, this is typical of what happens when alternative medicine proponents set out to sue science not to test the reality of their beliefs but to generate marketing tools to sell those beliefs to other clinicians and the public.

Posted in Herbs and Supplements

7 Comments

Evidence Update: New Study Finds no Benefit from Cold Laser for Dogs Having Surgery for Disk Disease

A hot topic in veterinary medicine these days is cold laser therapy. I’ve been reviewing the theory and research evidence for this treatment regularly from my first review in 2010 to my most recent look at the evidence in 2016. Overall, my conclusions have largely remained the same:

Lasers have significant measurable effects on living tissues in laboratory experiments, so it is plausible that they might have clinical benefits. The extensive research done in humans, however, has so far only found limited evidence to support the use of lasers in a few conditions, and high-quality controlled studies often contradict the positive findings of initial, small and poorly controlled trials.

The experimental evidence in veterinary species is mixed and low quality, and there are no high-quality published clinical trials validating laser therapy for specific indications. It is possible that high-quality research may one day validate some of the claimed benefits for laser therapy. However, at present the best that can be said about this intervention is that it appears promising for some conditions, such as wounds and musculoskeletal pain.

The growing popularity of lasers is based largely on anecdotal evidence and economic factors. Laser units are being aggressively marketed to veterinarians, often using unsubstantiated claims of clinical benefits. Laser therapy represents a potential source of income for practitioners and, of course, for laser device manufacturers. It appears likely that this profit potential contributes to an enthusiasm for laser therapy not matched by the quality of scientific evidence for its benefits to patients.

Veterinary therapies often lack robust high-quality clinical trial evidence to support their use, and this is not itself a reason to avoid these therapies. However, when employing interventions that have not yet been rigorously demonstrated to be safe and effective, we have a duty to acknowledge the limitations of the evidence. Clients should be fully informed about the uncertainties concerning the effectiveness of laser therapy and the potential for unforeseen effects. Established therapies with stronger evidence identifying their risks and benefits should take precedence over promising but unproven therapies like laser treatment. And those interested in promoting low-level laser, particularly those marketing laser equipment and training, should proportion their claims to the available evidence and assume some responsibility for developing the evidence base further so that practitioners and animal owners can make better-informed decisions about this practice.

Today I came across a new study looking at the use of cold laser in dogs having back surgery for intervertebral disk disease (IVDD). I have previously reviewed two other studies of laser for this purpose, one of which appeared to show some benefit and the other showed no effect. The new study is very similar in terms of the small sample size and the methodology, though it is generally stronger than the other two in terms of mechanisms that control for various types of bias and error.

Bennaim M, Porato M, Jarleton A, et al. Preliminary evaluation of the effects of photobiomodulation therapy and physical rehabilitation on early postoperative recovery of dogs undergoing hemilaminectomy for treatment of thoracolumbar intervertebral disk disease. AJVR 2017;78(2):195-206.

Briefly, the study classified dogs with severe neurologic symptoms caused by IVDD into groups based on the level of dysfunction. All dogs had surgical and standard medical treatment. Some also had laser therapy, some had physical therapy and fake laser treatment, and some had only standard care and fake laser treatment. The time to reach various stages of functional recovery and the amount of post-surgical intravenous pain medication each dog required were measured and compared between the groups. There were no differences in any of these measures between any of the groups. This indicates that neither laser treatment nor physical therapy added to surgery appeared to have any benefits above standard care.

The authors list a number of reasons why this negative result might have occurred even if laser therapy does actually have some benefit. The most plausible of these was the small sample size. A very large improvement due to laser could be seen even when evaluating only a relatively small number of patients, as in this study. However, if laser has some benefit and it is fairly small, it might not be possible to detect it in such a small study. Of course, the most likely explanation for the failure to find any benefit is simply that there is none.

Overall, these three studies do not provide much encouragement for using laser in dogs with IVDD. Only one of the three appeared to show any benefits, and that study lacked most standard controls for bias. The negative findings of the other two studies, especially the current study, which was the strongest of the three in terms of methodology, strengthens the view that laser therapy is not helpful for dogs having surgery for IVDD.

Of course, it is always possible that different laser treatment (different doses, duration of treatment, equipment, etc.) could be helpful, or that laser is useful for other conditions. We can, as always, only make provisional conclusions based on existing and imperfect evidence. With the evidence we have now, however, it seems likely that laser will not be helpful for dogs with IVDD that are severely affected enough to need surgery.

Posted in Science-Based Veterinary Medicine

12 Comments

Do Vaccines Cause Autism in Dogs?

Introduction

Before training as a veterinarian, I studied animal behavior. I worked with primates, and one of the most fascinating aspects of these animals was the deep similarity between their behavior and that of humans. Such similarities shouldn’t be surprising, of course, because we share many of the mechanisms that produce our behavior. Evolution has produced brains and sense organs and various anatomical and physiological systems for generating behavior, and many of these systems are shared between species. The more closely related, in evolutionary terms, the species are, the more such behavior-generating mechanisms they share, and the more similar their behavior is likely to be.

This, of course, applies to all species, not just between humans and other primates. It is not difficult to find great behavioral similarity among mammals, even between relatively distantly-related groups such as human and our canine and feline companions. The similarities may be fewer and the differences more noticeable, but we still share much of our basic biology, including the mechanisms that generate behavior, and we exhibit many behaviors that appear similar in form and function.

One major challenge in studying animal behavior is how to choose our terminology. Many of the words describing behavior in humans contain explicit or implicit information about mental states. If I say someone is angry or afraid, I am describing their feelings and internal experience directly, and presuming it conforms to general human patterns. But if I say someone is “cowering from her” or is “pummeling his face,” these descriptions of behavior contain implied mental states, of fear and anger respectively. So when we describe the behavior of animals, how do we handle the explicit or implicit attribution of mental states that we cannot verify are present or the same as those in humans when animals cannot verbalize their feelings and agree on appropriate descriptive terms? Should we avoid assuming mental states like our own, and if we should how do we accomplish this using language that so often contains implicit attribution of such mental states?

There is no simple solution to these questions. We can try to describe all behaviors mechanically, in terms of specific body movements, but that is cumbersome and arguably misses important and obvious attributes of the behavior. A dog and cat may both wag their tails, but the likely response if you persist in doing whatever you did to start the tail wagging is likely to be very different. The dog might well lick your face while the cat might as likely scratch it! Saying that the dog “wagged his tail playfully” and the cat “flicked her tail irritably” implies mental states we cannot absolutely verify, but these descriptions are a lot more useful and predictive of future behavior.

Some people object to at least some use of terms connoting mental states to dogs and cats because we cannot know their feelings with certainty, and because there are obvious cognitive differences between humans and our pets that influence the kinds of mental states we think it likely dogs and cats can have. There is, of course, a matter of degree in this. If we say “the dog is afraid” or “the cat is mad,” some people might object, but most would accept these terms as roughly appropriate. However, if say “the dog is skeptical” or “the cat is devout,” few people would accept those as legitimate because they imply thought processes we think our pets are unlikely to be capable of. There is, not surprisingly, a large grey area between these extremes.

There are pros and cons to using descriptions for feelings and behaviors in our pets that are commonly used to describe such feelings and behaviors in people. On one hand, we risk anthropomorphism, the attribution of human feelings and motivations to non-human animals. For example, people often describe their dog as looking “guilty” when he or she is punished for peeing in the house. It is unlikely, however, dogs, understand the kinds of obligations and social conventions required to feel guilty for violating a promise not to pee in the house. Thinking the dog can have this level of comprehension and the feeling of remorse can often lead owners to imagine intentions, a deliberate desire to defy the owner, that the dog also probably doesn’t have, which can negatively influence their bond with the pet and the way they try to alter the undesirable behavior.

Similarly, when a cat pees in the house while an owner is on a trip, the owner will often say the cat did it “because he was mad at me.” This generates a very different owner response than if we describe the behavior as “inappropriate urination associated with routine change: or something more emotionally neutral.

On the other hand, because humans share evolutionary relationships and many of the basic mechanisms of behavior with other animals, it is perfectly reasonable to assume significant similarity in the genesis of behavior and internal experiences. The presumption that humans are fundamentally, qualitatively different in every way from all other animals in their mental states or behavior is scientifically implausible, as well as being arrogant and self-serving. Mental similarities that correspond to similarities in behavior are a likely and parsimonious way of studying and characterizing animal behavior.

All of this is by way of introducing the real subject of this post, the question of whether dogs can fairly be described as “autistic” and, if so, whether we can blame this on vaccination

So Can Dogs Get Autism?

This question was recently brought to my attention by some fellow skeptics who pointed me towards a dramatic and inflammatory article on an anti-vaccine web site.

Autism Symptoms in Pets Rise as Vaccination Rates Rise from The Vaccine Reaction Web Site

As the title suggests, this article makes several claims about canine behavioral disorders and vaccines, which I will address individually:

- Pets, especially dogs, exhibit behavioral disorders that share some features of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and may also share some underlying causal mechanisms

- Vaccines in dogs cause a wide range of diseases, and among these is the appearance of abnormal behaviors following vaccination for rabies. These behaviors resemble autism in children.

- Vaccination are required by law and given by veterinarians even when they are clearly not necessary. This is both very profitable and likely associated with the increase in autism-like behavioral pathologies in dogs.

Dogs Get Autism (or something like it)

This seems to be the claim from this article that has struck skeptics as the most ridiculous or bizarre. The idea that dogs can get autism seems ridiculous on the face of it. However, part of the trouble here is the kind of issue of terminology I discussed earlier. ASD is challenging to define and identify in humans. Some of the characteristic symptoms relate to verbal and specifically human social behaviors. Since dogs cannot develop language and, obviously, are not human beings, they cannot be autistic if the word is strictly defined in terms of behaviors unique to the human species. Similarly, dogs cannot have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Panic Disorder, dementia, or any other psychopathology defined by behaviors or behavioral deficits unique to humans. Carried to a logical extreme, if one cannot be definitively said to experience fear, anger, sadness, or other emotions without verbally acknowledging these feelings or exhibiting them in characteristically human ways, then dogs cannot be described as having any of these feelings either.

However, dogs do share anatomic and physiologic mechanisms for generating their behavior that are homologous (meaning derived from the same evolutionary precursors and processes) to those which generate our behavior. And dogs do exhibit behaviors that look very much like fear, anger and sadness, as well as constellations and patterns of behavior that look very much like OCD, Panic Disorder, dementia, and ASD. Whether or not we choose to use the same descriptive terms for these behaviors depends more on our purposes and our concerns about the impact of this terminology on how others receive our arguments than on the question of whether the behaviors and their biological antecedents are related, which they very likely are.

The claim that dogs exhibit ASD-like behaviors is supported by citing the work of Tufts University veterinarian and behaviorist Dr. Nicholas Dodman. Dr. Dodman has published both research articles and popular books about animal behavior, and he frequently makes direct and explicit comparisons between clinical behavioral pathologies in humans and similar patterns of behavior in animals. The specific article cited in the Vaccine Reaction piece was a popular piece by Dr. Dodman in the magazine Psychology Today, Can Dogs Have Autism? Dr. Dodman addresses this question in a more academic manner through a number of scientific reports (e.g. 1, 2). He has also studied a number of other behavioral pathologies in dogs and other species which he suggests may have meaningful similarities to OCD and Tourette’s syndrome.

I have mixed feelings about Dr. Dodman’s use of human diagnostic terminology in reference to behavior problems in non-human animals. I agree that there are striking similarities in some of the patterns of behavior he identifies, and I think investigating potential shared causal mechanisms is worthwhile. To the extent that animal models of human disease share manifestations and causal mechanisms, identifying them can improve our understanding of these diseases in humans as well as the model species. This is a standard part of medical research, and there is no fundamental reason it shouldn’t be applied to behavioral disorders.

I also think that by communicating with the general public about this kind of research can generate better public understand and support for the research and for science generally, which is desperately needed now more than any time in the past century. Dr. Dodman has had great success in sharing his passion and the subjects of his research with the public, and I think that is worthwhile even if not every hypothesis he comes up with ends up being correct.

However, I also recognize the dangers of labeling non-human behavioral disorders with diagnostic labels developed for use in people. Even when there are shared features and casual mechanisms involved, there are also meaningful differences between the human disorders and those seen in other species. A key feature in many cases of ASD, for example, involves abnormalities in language development. This is a core aspect of human behavior, and a large part of the real-world problems an ASD diagnosis creates for patients and their families. Identifying tail-chasing in bull terriers as “autism” runs the risk exaggerating or oversimplifying the similarities between the disorders, which can interfere with full and accurate understanding of them. Such use of language can also be misinterpreted as demeaning to human ASD patients. Comparisons of stigmatized human groups to animals has long been a powerful weapon against these groups, and while I have no concern that Dr. Dodman has any such ill intent in his use of human diagnostic terms, I can see how his legitimate scientific background could appear to legitimize misuse or misinterpretation of his work by others.

That is, in fact, what has occurred in the Vaccine Reaction article. While the reference to Dr. Dodman’s work on ASD-like behavior in dogs is generally accurate, it is juxtaposed to completely inaccurate claims about vaccines, including the claim that they are a causal agent in ASD. This implies that Dr. Dodman’s work supports a link between vaccination and ASD or other behavioral pathology, which it most absolutely does not.

On balance, I don’t believe the claim that dogs can get autism is as unreasonable or prima facie ridiculous as it seems to some people. I think he has some evidence to support meaningful similarities between some canine behavioral pathology and ASD, and I think further investigation of these similarities could possibly lead to better understanding of the causes and mechanisms of ASD. However, I also believe that there are important differences between canine and human cognition and behavior that mean humans and dogs cannot both be “autistic” in precisely the same sense. An animal model of a human disease is, for all its usefulness, a model, not the disease itself, and there are always differences that matter.

I see both the advantages and disadvantages to using a shared term to describe similar, and potentially causally related, behavioral disorders in humans and dogs. To some extent, it may be fair to say that dogs get autism, but when exploring the meaning of this label more fully we must acknowledge and bear in mind the differences between the species as well so we aren’t misled by a simplistic or excessive concept of equivalence between human and canine behavioral disorders.

Vaccines Cause All Sorts of Diseases, Including Rabies-like Behavior or Canine Autism

My response to this claim is far less complex and nuanced: bullshit!

To expand on that further would require rehashing lots of subjects I’ve written about before. Instead, I will say only that while vaccines can cause both minor and serious adverse effects, they do so rarely, their benefits far outweigh their risks in most cases (for core vaccines, such as rabies, for example), and there is no such thing as “Rabies Miasm,” “Chronic Rabies” or “Canine Autism” that can be blamed on rabies vaccination. Here are some posts dealing with these and other anti-vaccine claims in more detail:

Rabies Vaccines & Aggression in Dogs-Pure Pseudoscientific Fear Mongering

Thimerosal–Should I worry about mercury in vaccines for my dog or cat?

“One and Done” Approach to Rabies Vaccination is Misguided and Dangerous

What You Know that Ain’t Necessarily So: Vaccination & Autoimmune Diseases

Antibody Titer Testing as a Guide for Vaccination in Dogs and Cats

What’s the Right “Dose” of a Vaccine for Small-Breed Dogs? (and a follow-up post)

Pox Parties for Dogs: Brought to You by Veterinary Homeopaths

Routine Vaccinations for Dogs & Cats: Trying to Make Evidence-based Decisions

One additional point does need to be made, however.

VACCINES DON’T CAUSE AUTISM!!!

The evidence for this conclusion is overwhelming (e.g. 1, 2, 3). I contacted Dr. Dodman after seeing his work used to imply a causal relationship between autism and vaccines, and he was unequivocal in his response. He does not believe that vaccines are a cause of autism, in humans or in dogs, and he rejects any suggestion that his work might support this false claim.

More Vaccines = More Autism in Dogs

Bullshit redux. It is not even clear that dogs are being vaccinated more than in the past. Recent changes in our understanding of the average duration of immunity and other variables have led many vets to change vaccination practices, so quite a few of us are actually vaccinating less than we used to. There certainly are too many vets who haven’t kept up with the science in terms of vaccinating more than is necessary to provide protective immunity for some diseases, and revenue is likely one of many factors in this. Between changes in vaccination protocols and hesitancy about vaccination on the part of pet owners, it is as likely that vaccination rates have declined rather than increased in the last decade. However, I am not aware of any reliable data on this subject, and none was provided in the Vaccine Reaction article. Regardless of whether vaccination of dogs is increasing or declining, there is no evidence that vaccines are related to behavioral pathology in dogs, ASD-like or otherwise, and this is just another of the many false claims made in the article.

Bottom Line

There are behavioral disorders in dogs that share symptomatic and possibly causal features of behavioral disorders in humans. While the use of human diagnostic terminology in dogs is problematic, it is not unreasonable to suggest dogs may have behavioral syndromes similar in symptom pattern and causal factors to autism and other human disorders. Animal models of human disease are an established and useful element of medical research, and this can be reasonably applied to behavioral disorders if done judiciously. Dogs clearly do not get autism as it is defined and exhibited in humans, but they may well have related disorders that can provide insight into the causes and treatment of autism in humans.

Regardless of whether or not we choose to call similar or related disorders in dogs and humans by the same name, we can at least be confident of one key fact:

VACCINES DON’T CAUSE AUTISM!!!

Posted in Vaccines

3 Comments