WHAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE (EBVM)?

Evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) is the formal, explicit application of the philosophy and methods of science to generating understanding and making decisions in veterinary medicine. It is often associated with academic research and university or specialty practice. However, EBVM also provides a perspective and a set of behaviors veterinarian in clinical practice can employ to control bias, reduce errors, and manage information more efficiently in general practice as well. In this setting, where limited time and resources and the agendas of our clients constrain our actions, EBVM can facilitate better clinical decision making and improve patient care, aid in managing uncertainty, communicating effectively with clients, and establishing habits to facilitate ongoing learning and improvement throughout one’s career.

WHAT CAN EBVM DO FOR ME?

The main benefit of employing EBVM techniques is having better information on which to base our clinical practice. When there is good quality evidence to help us evaluate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, EBVM helps us find this evidence and learn how to use it to inform our decisions. When, as is often the case, the evidence is poor in quality and quantity, understanding this helps us to avoid the risks of unjustified certainty and be mindful of the need for flexibility and lifelong learning in clinical practice.

Better information, and more informed decision making, leads to better patient care. There is evidence from human medicine that the implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and other EBM tools improves patient outcomes, and this is the goal of EBVM as well.

Finally, EBVM can help practitioners meet our ethical obligations to patients and clients. We have a duty to our patients to provide the best care possible, and EBVM facilitates this. We also have a duty to provide truly informed consent to our clients. Only by understanding the evidence behind our recommendations, and having a clear view of the degree of uncertainty present, can we effectively guide clients in making decisions for their animals.

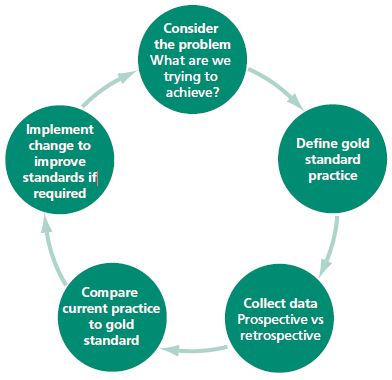

THE STEPS OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE Evidence-based practice involves following a set of explicit steps to integrate formal scientific research information with the individual circumstances of each case to facilitate decision making. The busy practitioner will clearly not be able to execute each step for every problem in every case, nor is this necessary. But by regularly employing the EBVM process, we build and maintain a knowledge base that informs our decisions.

Of course, every veterinary clinician already has extensive knowledge and opinions that inform his or her practice. However, without EBVM, our knowledge base is haphazard and uncritically derived from sources of unknown or low reliability. EBVM allows us to have greater confidence in the knowledge we rely on when making recommendations for individual patients.

These are the basic steps of EBVM:

- Ask useful questions

- Find relevant evidence

- Assess the value of the evidence

- Draw a conclusion

- Assign a level of confidence to your conclusion

Asking Useful Questions Vague or overly broad questions impede effective use of research evidence in informing clinical practices. “Does drug X work?” or “What should I do about disease Y?” are not questions that are likely to lead to the recovery of useful information from published research. There are a number of schemes for constructing questions the scientific literature can help answer. One of the easiest is the PICO scheme.

P– Patient, Problem Define clearly the patient in terms of signalment, health status, and other factors relevant to the treatment, diagnostic test, or other intervention you are considering. Also clearly and narrowly define the problem and any relevant comorbidities. This is a routine part of good clinical practice and so does not represent “extra work” when employed as part of the EBVM process.

I– Intervention Be specific about what you are considering doing, what test, drug, procedure, or other intervention you need information about.

C– Comparator What might you do instead of the intervention you are considering? Nothing is done in isolation, and the value of most of our interventions can only be measured relative to the alternatives. Always remember that educating the client, rather than selling a product or procedure, should often be considered as an alternative to any intervention you are contemplating.

O– Outcome What is the goal of doing something? What, in particular, does the client wish to accomplish. Being clear and explicit, with yourself and the client, about what you are trying to achieve (cure, extended life, improved performance, decreased discomfort, etc.) is essentially in evidence-based practice.

FIND RELEVANT EVIDENCE

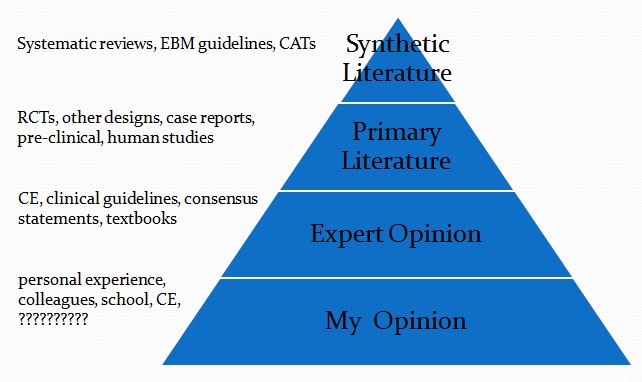

Experienced clinicians typically have opinions on the value of most interventions they routinely consider. Unfortunately, we rarely know where those opinions originally came from or how consistent they are with the current best scientific evidence. And given the constraints of time and resources, practitioners will rarely have the ability to find and critically evaluate all the primary research studies relevant to a particular question. Fortunately, there are sources of evidence that can provide reliable guidance in an efficient, practical manner.

The best EBVM resource for busy clinicians is the evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. These are comprehensive evaluations of the research in a general subject area that explicitly and transparently identify the relevant evidence and the quality of that evidence and make recommendations with clear disclosure of the level of confidence one should place in those recommendations based on the evidence.

Sadly, many guidelines produced in veterinary medicine are not evidence based but opinion-based (so-called GOBSAT or “Good Old Boys Sat At a Table” guidelines). These are no more reliable than any other form of expert opinion. Excellent examples of truly evidence-based guidelines are those of the RECOVER Initiative for small animal CPR and the guidelines produced by the International Task Force for Canine Atopic Dermatitis.

After evidence-based guidelines, the next most useful resources are systematic reviews and critically-appraised topics (CATs). These are more focused but still explicit and transparent reviews of the available evidence on specific topics. Systematic reviews can be identified by searching the VetSRev database, a free online resource produced by the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (CEVM) at the University of Nottingham. Unfortunately, getting full-text copies of these reviews can be challenging for vets not at universities, but there are a number of options depending on where one practices.

Critically appraised topics are also produced by CEVM and freely available on the web as BestBetsforVets. There are a number of other free CAT resources, including the Banfield Applied Research and Knowledge web site.

Finally, primary research studies are a useful source of guidance for clinicians, though they take more effort and expertise to find and critically evaluate.

ASSESS THE VALUE OF THE EVIDENCE

The most challenging part of the EBVM process for vets in practice is critical appraisal, learning to identify important limitations in published research study that affect how confident we can be in the conclusions and how relevant they are to our patients. There are resources available to teach these skills, and hopefully this will become more common in veterinary colleges, but for most practitioners pre-appraised evidence, such as guidelines and systematic reviews, will be more useful.

The clinician still has an important role, however, in determining the relevance of research evidence to individual patients. The details of a patient’s medical condition, the values, goals, and resources of the owner, and the expertise and resources available to the veterinarian all determine the degree to which a particular conclusion based on formal research is applicable to a given patient. The role of EBVM is not to replace clinician judgment with automatic reliance on published research but to ensure the clinician has the best available information and understands clearly what is known and not known when tailoring the evidence to the needs of individual animals.

DRAW A CONCLUSION

Ultimately, the job of a veterinarian is to guide the client in making decisions about care for their animals. When the clinician is aware of the existing evidence and its limitations and clearly appreciates the degree of uncertainty, then he or she can best help the client to understand their options. Making evidence-informed decisions and clearly communicating with clients about the needs and choices for their animal is the core of clinical veterinary medicine, and this is what the tools and methods of EBVM exist to support.

ASSIGN A LEVEL OF CONFIDENCE TO YOUR CONCLUSIONS

Often, the relevant research evidence is incomplete or flawed, and sometimes there is little or no such evidence applicable to a given patient’s needs. EBVM is still useful in this situation, because it allows us to clearly, systematically identify and communicate the uncertainty inherent in our work.

It is also important that we openly discuss with clients our use of evidence to inform our recommendations. Research has suggested that clients want to be told about the uncertainties involved in the treatment of their animals, and that discussing this does not reduce their confidence in their veterinarians. Clients also identify truthfulness as their highest priority in communication with their vet. By explicitly discussing our process in identifying and evaluating relevant evidence, we enhance our clients’ understanding of the role we play, and we help them to appreciate the value of our expertise, not only the products and procedures we sell.

EBVM AND THE GENERAL PRACTITIONER

The job of the general practitioner is to be informed about the research evidence relevant to their patients’ needs and to think critically about this evidence and the uncertainty it contains. It is also the role of practitioners to communicate clearly with clients about this information and guide them in making informed decisions. Ideally, general practitioners can also contribute by sharing what they learn in applying the EBVM process. Critically appraising individual studies or synthesizing the literature on particular questions will create useful information that can then be shared with colleagues.

Properly applied and with adequate support, EBVM can enhance the quality of information supporting the decisions and recommendations of vets in clinical practice. This not only reduces stress and wasted effort for veterinarians but improves client communication and patient care.