I have been able to get a look at the published paper for the study I recently discussed by Dr. Jean Dodds investigating giving lower doses of vaccine to small breed dogs. There is nothing in the published report that changes my earlier conclusion. This study adds nothing of substance to our understanding of optimal vaccination practices. In design and execution, it is simply a marketing tool to promote a set of pre-existing beliefs about vaccination, and in itself does not help to clarify what optimal vaccination practices might be.

The argument Dr. Dodds seems to be making contains a number of elements I agree with and believe to be supported by good science:

- The effectiveness and duration of immunity vary by vaccine type and with many other factors, but in general core canine vaccines are very effective at preventing illness and likely most pets who receive the initial vaccine series at the appropriate time are well-protected for at least 3 years and probably much longer.

- Vaccines can have adverse effects, and while these are rare they can be potentially serious. The precise factors that make some individuals more susceptible to such reactions than others are unclear, but size appears to be a factor, with small-breed dogs reporting more reactions that larger breeds. (this is quite a bit more restrained than previous statements she has made about “vaccinosis” in small animals)

- Avoiding unnecessary vaccination in animals already immune to particular infectious diseases is a desirable goal.

- Titers can often tell us if an animal is already immune, depending on the disease in question, though they generally cannot tell us if the animal is vulnerable to a disease since they only reflect part of the overall immune response.

She adds to these a number of claims which are not supported by good evidence, including most of the claims related to this specific study.

The dose of canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine parvovirus vaccine (CPV) vaccines can be reduced to 50%, but not more, for small breed and small mixed breed type dogs, based on body weight, and still convey full duration of immunity.

She states this in the introduction, indicating it is a pre-existing belief she intends to buttress with this study. However, her citations for this very clear and specific claim include three of her other papers expressing this opinion and an editorial from 1999 discussing concerns among practitioners about vaccination practices. No specific research is cited that supports this claim. And elsewhere in the paper, she makes it clear that the claim is actually based primarily on her personal experience, aka anecdotal evidence.

In the informed consent sheet for clients, she says “Clinical experience has shown…” and “One of the principal investigators has nearly five decades of clinical and research experience with vaccinations in companion animals. This experience has shown…” and then repeats this claim. It is not a claim supported by research evidence but simply something she has come to believe based on patients she has seen, and it should be clearly presented as such, as mere opinion appropriate for generating a hypothesis but not for making confident claims.

The only relevant research she cites is one study in which children were shown to have an adequate protective response to a lower quantity of Hepatitis B vaccine. This was tested primarily to reduce the cost of vaccination and make vaccination available to more people, not to avoid adverse effects. But in any case, it doesn’t validate the general concept that vaccines should be dosed by body weight, which is not accepted vaccine science in human or veterinary medicine.

As for the study itself, it suffers from many serious flaws that likely would have prevented publication in an ordinary veterinary journal, which may be part of why it appears in the journal of the AHVMA.

The first issue is selection bias. The subjects were recruited by an announcement on Dr. Dodds’ web page and emails to “holistic veterinarians.” This does not appear to have been very successful since only 13 animals were recruited. But in any case, these likely represent an unusual patient population, since “holistic” veterinarians, and of course Dr. Dodds, recommend quite different approaches to preventative and therapeutic healthcare than most vets, including different vaccination practices. These animals may not be sufficiently similar to pets that receive standard veterinary care, including with respect to their vaccine history. This would limit the ability to generalize any results to other populations.

Another problem was the lack of any standard definition for “a half dose of vaccine,” which is what participating vets were told to give. While all used the same specific vaccine, this vague description of the main intervention being tested allows for a lot of unpredictable variation from subject to subject, and makes it hard to compare with any other research that may be done. The specific antigenic load given would be much more useful information at this stage of research.

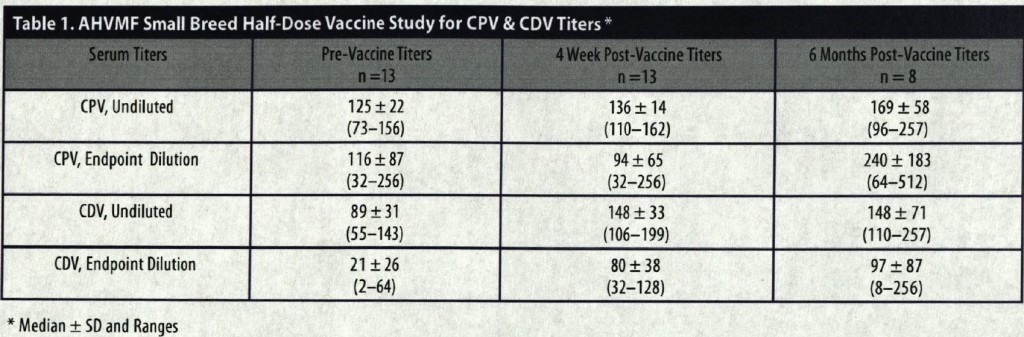

A core problem with the study is that it did not address any of the underlying issues of whether giving a half dose of vaccine would protect dogs as well from disease or reduce the number of adverse vaccine reactions. Neither of these subjects was evaluated in any of the study dogs. All that was done was that antibody levels were measured before vaccination and at 4 and 6 months later. Here are the main results:

All dogs had titers considered indication of immunity before being vaccinated. Most, but not all, dogs had an increase in their titer after vaccination at 4 months (9/13 for CPV and 11/13 for CDV) and 6 months (6/8 for CPV and 3/8 for CDV). This tells us, at most, that a smaller amount of a vaccine than usually given promotes some increase in antibody levels for CPV and CDV for some dogs. This, unfortunately, tells nothing about how to best vaccinate dogs to protect them from these diseases while minimizing any adverse health effects.

(The difference in the number of samples at 4 and 6 months reflected that while all dogs had blood samples taken at both times, “5 dogs had samples drawn at 6 months but these were inadvertently discarded.” Accidentally throwing out nearly ¼ of your samples is a pretty serious error in any study, and raises questions about the validity of the data as well as the conclusions.)

These data, even if accepted as legitimate, do not answer any of the pertinent questions, such as whether dogs receiving half of the usual vaccine dose would be protected as well long-term or healthier and less likely to experience health problems than dogs receiving the usual vaccine dose. The study doesn’t, in other words, provide any real evidence to support or refute the claims Dr. Dodds and many other “holistic” vets make about the best vaccination practices. And given she has admitted that she had no intention of following these dogs further or conducting any larger trials based on this “pilot” study, it is pretty clear that the only purpose of this study was to generate ammunition for a marketing campaign to promote ideas about vaccination that Dr. Dodds has developed entirely based on personal experience and belief.

I have addressed both the evidence concerning risks and benefits of vaccination and the issue of using titers to help make vaccination decisions. Limitations in the available evidence make a variety of different practices equally justifiable. While I probably vaccinate less than many conventional vets, I refrain from making definitive statements beyond the evidence about the effects of various approaches to vaccination. Dr. Dodds’ position is somewhat intermediate between the rabidly anti-vaccine views of some holistic vets and the unthinking annual vaccination too often still recommended by many conventional vets, and she and I are probably not too far apart in principle. However, she chooses to emphasize the risks of vaccination (especially in places where, unlike this article, she talks about nonsense like “vaccinosis”), and she makes confident claims about the best vaccination approach that she presents as science-based but which really are simply her opinion.

In this study, she has provided the illusion of scientific evidence to support these claims, but the reality is that this study is too flawed in design and execution to add anything useful to the question. Unfortunately, Dr. Dodds and others are already promoting it widely as evidence that their preferred vaccination approaches are better for patients than those of others, including the current most evidence-based guidelines. This is a misleading misuse of science consistent, unfortunately, with her approach in many other areas.