Why Ask Why?

There are many reasons people are interested in the causes of cancer in pets. On a purely emotional level, it is natural to ask “Why?” when something terrible happens, such as the diagnosis of cancer in a beloved animal companion. I suspect this is deeply rooted in human nature, in the drive to understand and predict the environment so that we can control it. On a rational level, of course, understanding the causes of cancer could be expected to give us exactly the control we yearn for, the ability to prevent it. Both our rational and emotional aspects push us to seek for causal patterns.

Unfortunately, there is a negative side to this search for causes. As Tim Minchin once remarked in another context, our drive to find the causes for things helps us to find meaning where there is none. We are sometimes so desperate to find a cause we can control, we allow our desperation to overwhelm reason and evidence and find causality where there is none.

This explains much of the dubious reasoning of alternative medicine. The ubiquitous and mistaken identification of mysterious “toxins” as the cause of so many ills, including cancer, is a product of our need to believe we can protect ourselves and our pets from these ills by avoiding or removing these toxins.

The entire pseudo-discipline of homotoxicology is predicated on toxins as the cause for all disease. And many other alternative approaches see toxins as a major threat. Detoxification is part of the claims made by proponents of so-called Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM), veterinary homeopathy, herbal remedies for pets, energy therapies such as Reiki, and others. And toxins are routinely claimed as a cause of cancer in pets. Some of the toxins claimed to cause cancer include vaccines, commercial pet food, flea and tick control products, fluoridated water, electromagnetic radiation, and more.

Clearly, a major reason for citing such environmental factors as causes of cancer in our pets is to support further claims that we could prevent cancer by avoiding these factors or counteracting their ill effects. As I’ve already mentioned, this kind of reasoning is both a rational collection of hypotheses that can be tested and a deeply ingrained emotional need to seek control and protect ourselves, and our pets, from awful things like cancer. Unfortunately, the emotional aspect of this tendency often overwhelms the rational aspects, leading us to see cancer-causing poisons even where the evidence suggests they aren’t really present.

Certainly, some environmental factors, including things that can reasonably be called “toxins,” do increase cancer risk. The archetypical example is cigarette smoking, which is a clear and strong risk factor for certain kinds of lung cancer. Many other such risk factors have been identified and demonstrated to have causal relationships to specific cancers, from chemicals in food and water to infectious disease organisms and even medical interventions such as vaccination and chemotherapy. This is extremely useful because it allows us to avoid such exposures and potentially reduce the risk of cancer. It is almost a certainty that additional environmental risk factors for cancer will be found that are now unknown and that will increase our ability to reduce the occurrence of some cancers.

But how much of the cancer that occurs can we really blame on environmental factors? A new study has provided a suggestion that it may be less than we usually think.

The Study

Tomasetti, C. Vogelstein, B. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2 January 2015: 78-81.

Some tissue types give rise to human cancers millions of times more often than other tissue types. Although this has been recognized for more than a century, it has never been explained. Here, we show that the lifetime risk of cancers of many different types is strongly correlated (0.81) with the total number of divisions of the normal self-renewing cells maintaining that tissue’s homeostasis. These results suggest that only a third of the variation in cancer risk among tissues is attributable to environmental factors or inherited predispositions. The majority is due to “bad luck,” that is, random mutations arising during DNA replication in normal, noncancerous stem cells. This is important not only for understanding the disease but also for designing strategies to limit the mortality it causes.

The basic events leading to cancer are pretty well understood. Cells in our bodies divide and reproduce all the time. If they didn’t, we could never grow, or repair wounds, or maintain the health and functioning of our organs. Mutations in some genes lead to uncontrolled division of cells, which can become a cancer. These mutations may occur in genes that stimulate cell division, genes that would normally control cell division, or other genes involved in the regulatory processes that prevent cancer but allow necessary growth and repair of tissues. The specific type of cancer depends on the type of cell and tissue involved and the particular mutations leading to loss of control over cell replication. The details are complex and not entirely understood, and they vary from cancer to cancer, but the general outline of the process is well-established.

The reason environmental factors can increase the risk of cancer is that they influence the occurrence of mutations. However, it is rarely as simple as one toxic exposure leading to one mutation leading to cancer. For cancer to develop, typically many things need to go wrong together, many genes to function abnormally at the same time. And environmental exposures are not on/off switches for genetic mutations. They influence the probability of such events in an often unpredictable way that is itself affected by dose, individual susceptibility, and many other factors.

One person may smoke for decades and never get lung cancer, while another may only smoke for a few years, or not at all, and get lung cancer anyway. And cancer is typically more common in some tissues that in others, sometimes in ways inconsistent with differences in potentially toxic environmental exposures. For example, the small intestine is constantly exposed to potential carcinogens from the environment, while such things very rarely ever reach the brain, yet brain tumors are far more common than small intestinal cancers. What the authors of this paper have done is offer a possible explanation for differences in the risk of different kinds of cancer: bad luck!

Basically, what they are arguing is that most mutations leading to cancer happen by chance, not as a result of an environmental or genetic cause. The way they evaluated this idea is by looking at the rate of cell divisions in different tissues. As I said before, cell division happens all the time as part of the normal functioning of our bodies. However, some tissues repair and replace cells more rapidly and more often than others, and this is reflected in a greater number of cell divisions occurring in the stem cells of those tissues, that is in the progenitor cells that are responsible for producing all of the new functional cells in each tissue. Because each cell division event is an opportunity for a mistake in the copying of DNA, a mutation, the more cell divisions that happen, the more opportunities for mistakes that can lead to cancer.

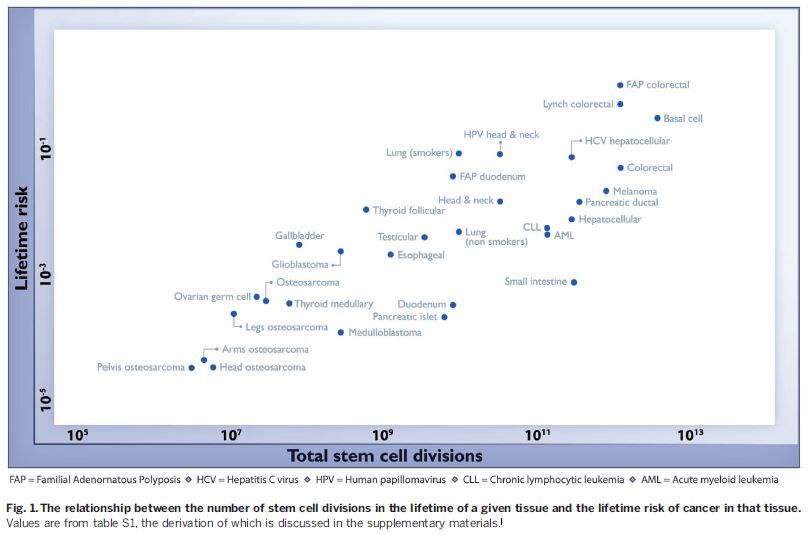

This study found a strong and consistent correlation between the rate of cell division in each tissue and the reported incidence of cancers from that tissue in the population. Here’s what that looks like graphically:

As you can see, cancers are more common in tissues with higher rates of stem cell division, consistent with the hypothesis that many cancers occur by chance, simply as a function of errors during normal cell division, not as a consequence of some environmental of genetic factor.

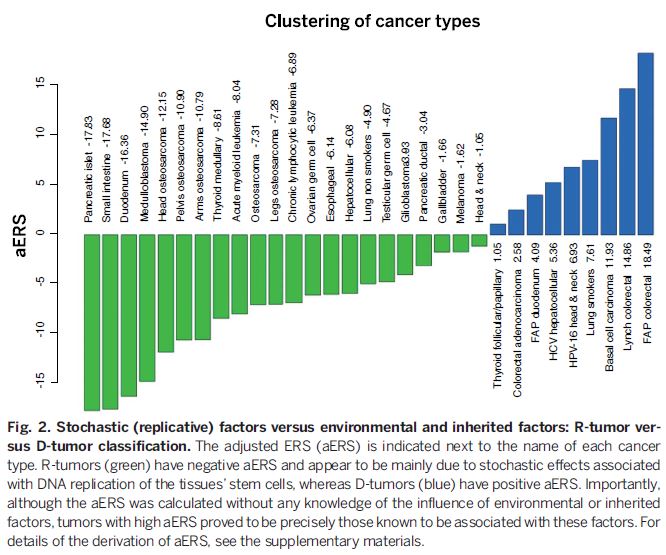

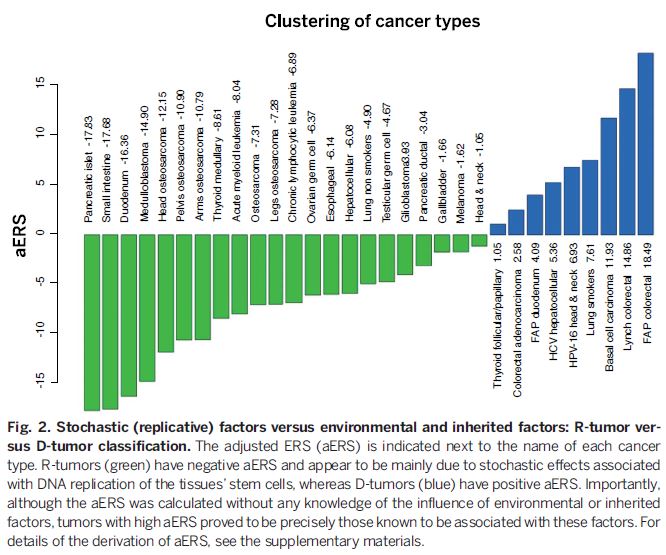

Of course, life is almost always more complicated than the simple hypotheses we come up with to explain it. The authors did some further analysis to try and separate the contribution of chance and other factors, such as environmental exposures and genetic predisposition, in the formation of particular types of cancer. What they found was that cancers can be separated into different categories, some more likely to be caused by environmental or genetic factors and some more frequently due to chance.

Cancers on the right and in blue are those for which genetic and environmental factors play a large part in the risk of their occurrence. Examples are lung cancer in smokers and head and neck cancers caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV). For the other cancers, in green on the left of the chart, chance mutations play a dominant causal role. Of course, chance plays a role in all types of cancer, since even people with known risk factors, like smoking or HPV infection, do not always develop cancer. Overall, the authors’ work suggests that about 65% of the difference in cancer risk between different tissues is due to differences in the inherent rate of cell division in those tissues, in other words to chance.

So What?

This paper has been interpreted in the media as indicating that most cancers are caused by bad luck (random mutation). As has been pointed out elsewhere, this isn’t really an appropriate interpretation of the statistics in this paper, which only tell us something about the difference in the rate of cancer development in different tissues, not the actual chances of cancer occurring in individuals. And as the authors themselves point out, the role of chance mutations compared to environmental factors is different for different cancers. It is likely, for example, that chance plays a pretty small role in the chances of a smoker getting lung cancer since the effect of smoking is strong. The devil is, as always, in the details, and the details are complicated.

What the paper does illustrate, however, is that chance does play a large role in the development of cancer, and in some cases in is likely the most important factor. Our natural inclination to seek preventable causes for disease, which is at least as much a psychological mechanism for controlling our fear as it is a rational approach to preventative healthcare, makes us resistant to the idea that much of the risk for cancer in ourselves, and potentially our pets, is due to chance, to luck. It may be disheartening to accept this since it implies we cannot control all the risks or prevent cancer from happening.

But knowing how nature really works is always better than relying on our fantasies of how we would like it to work. If we appreciate the role of chance in the development of cancer, this can provide many benefits. For one thing, we can use the knowledge to help us stop worrying unnecessarily over things we cannot control. And we can stop wasting time and energy trying to avoid environmental factors that probably have little, if anything, to do with the chances of developing cancer. Even more importantly, perhaps we can stop avoiding things that are actually more beneficial than harmful, such as vaccinations, if we understand the statistical reality that their contribution to cancer risk is often very, very small, and negligible compared with their beneficial effects.

Much of what happens to us in life comes down to chance, to luck. Certainly, we should make reasonable efforts to identify preventable causes for diseases like cancer. But we will be far more effective at maintaining and restoring health if we focus our attention and energy on things that actually matter, rather than obsessing about illusory risk factors that provide us only with comforting magic rituals rather than real preventative healthcare strategies.

If this study is borne out and it is true that most cancer arises from chance mutations rather than genetic or environmental risk factors, then we will help far more people and pets by focusing on early detection and effective treatment than by warding off imagined evil toxins through bogus practices like homotoxicology or other “detoxification” schemes.

Another potential benefit of recognizing the large role of chance in the development of cancer might be that we can stop blaming ourselves when our pets develop these diseases. So many of the testimonials I see for unproven, unscientific or outright quack therapies begin with heart-wrenching stories about the death of a beloved pet from cancer. The dark side of our obsession with finding and controlling risks is that we tend to feel we are at fault when something bad happens. This self-recrimination is not only unnecessary pain we cause ourselves, it is itself a potential source of danger to our pets when it drives us to seek protection from unproven and pseudoscientific approaches.

Recognizing the role of chance in the occurrence of cancer is not a cause for despair but an opportunity to reap the benefits of acceptance. Realizing that not everything can be controlled, we can avoid the pain and wasted energy of trying to control everything, the guilt when bad things happen anyway, and the dangers of choosing magic rituals to ward of imaginary causes of illness over sound, scientific approaches to preventing, detecting, and treating disease, including cancer.