Introduction

One of the most frequent recurring topics on this blog has been stem cell therapies. Generally, I have concluded that various types of stem cell therapies are plausible and promising, but they are unfortunately being marketed with claims and uses that go far beyond any reasonable scientific evidence. Since the last time I reviewed the subject, a couple of interesting articles have been published, so I thought it was time for an update.

Research Review

The first is a narrative review of companion animal stem cell studies published earlier this year.

Andrew M. Hoffman, Steven W. Dow. Concise Review: Stem Cell Trials Using Companion Animal Disease Models .STEM CELLS 2016;34:1709–1729

As a narrative review, this paper does not have the rigor, controls for bias, or focus of a systematic review. However, it provides a nice informal summary of the problems for which stem cell therapies have been investigated in companion animals, the different types of therapies evaluated, and the strengths and weakness of the literature. The paper reviewed companion animal stem cell studies from 2008 through 2015.

The key findings are that there are not many studies, the studies that exist are very inconsistent in terms of the specific treatment they tested, and almost all of the studies have significant limitations.

Arthritis is the most common problem for which stem cell therapies have been investigate in companion animals. However, the specific therapies used are always somewhat different, so there is no replication or consistency in the literature. Studies use different doses, preparation methods, methods of administration, sources of stem cells, and measures of effect. This hodgepodge of methods indicates the very early stage of research in this area, and we cannot yet draw reliable conclusions about the value or safety of particular products for specific uses. And most studies included only a handful of patients, which significantly weakens any conclusions based on them.

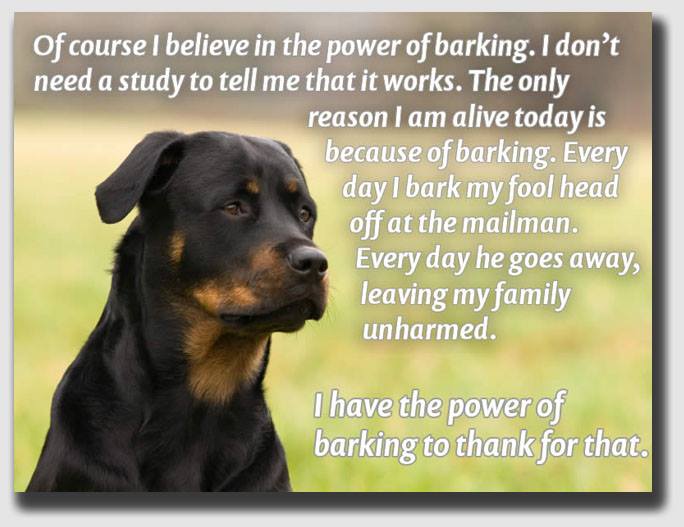

In addition, the majority of the studies did not employ the basic mechanisms of controlling for bias and error, including randomization of subjects, blinding of clients and investigators, and placebo controls. Subjective measures of effect were also most commonly used, which make the lack of such bias control methods particularly significant. While most studies claimed to find some beneficial effects, these claims have to be taken with a grain of salt due to these methodological issues.

The same general issues pertained to the other clinical problems for which stem cells have been studied. Intervertebral disk disease, inflammatory bowel disease, dry eye, kidney disease, and a few other conditions have been the subject of stem cell studies. These again involved very few patients, a variety of quite different treatments, and few if any controls for bias, confounding, and other important kinds of error. The results were inconsistent, some showing apparent benefits and others not, and a few showed evidence of some short-term side-effects. Overall, no general conclusion about the clinical value of stem cell therapies for any of these conditions can be justified by the existing research.

The authors conducted the review primary to make the case that companion animals might make a good research field for studying stem cell therapies with a long-term goal of applying them to humans. However, even with an optimistic slant, the authors’ conclusions were quite cautious:

In conclusion, companion animals with naturally occurring diseases analogous to human conditions can be recruited into clinical trials and provide realistic insight into feasibility, safety, and biologic activity of novel stem cell therapies.

However, improvements in the rigor of manufacturing, study design, and regulatory compliance will be needed to better utilize these models… Based on review of the literature, the utility of companion animals in stem cell trials is in the very early stages.

They also provided some recommendations for ways to improve the companion animal literature on stem cells, which would benefit both those with the ultimate goal of treating humans and those of us interested in finding safe and effective treatments for veterinary patients.

To facilitate expanded development and application of companion animal disease model research in the future, the following areas need to be addressed with additional education, communication, and industry and government support:

Increased collaborations between physicians and veterinarians to address specific disease conditions and models, consistent with the One Health paradigm.

Increased understanding of the molecular pathology of specific diseases in companion animals, and detailed comparison to human samples and analogous disease processes.

Greater characterization of companion animal stem cells and their cellular products.

The use of more rigorous double blind (owner, investigator) randomized clinical trial designs whenever possible. Education of the public about the value placebo-controlled studies.

Greater clinical trial infrastructure (personnel, equipment, specialized instrumentation, and imaging) to support efficient recruitment into clinical trials.

Central registry of veterinary clinical trials (currently in progress at the American Veterinary Medical Association).

Biorepositories and registries of companion animal disease tissue, biofluids, and nucleic acids or other samples.

Improved availability of companion animal specific reagents, in particular probes for protein detection and quantification.

The application of FDA guidance (NADA, INAD, pre-IND) in clinical trials involving stem cell treatments in companion animals (client owned animals).

I have highlighted a few of the recommendations of particular importance for making such research useful to veterinary patients. The establishment of a clinical trial registry, improved rigor and quality of research, and the application of FDA-level standards would all greatly improve the quality of stem cell research in veterinary medicine and improve the chances of finding truly useful therapies. This last measure is particularly relevant to the other study I wanted to discuss.

Allogenic Stem Cells for Arthritis

Harman R, Carlson K, Gaynor J, et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Masked, and Placebo-Controlled Efficacy Study of Intraarticular Allogeneic Adipose Stem Cells for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis in Dogs. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2016;3:81.

This is by far the best quality stem cell research study I have yet seen, and the reason is likely that the study is part of an effort to get FDA approval for a specific stem cell treatment. While the study has limitations, as all research does, it is well-designed and conducted and provides pretty robust results.

The major limitations are that the study was industry funded, which has been associated with some risk of bias in human pharmaceutical research, and the outcome measures were quite subjective. However, the mechanisms for controlling potential bias were quite thorough, including appropriate randomization, blinding, pre-specific outcome measures, and a lack of the statistical hocus pocus that is so common in veterinary clinical trials. Overall, the study provides very good evidence for a potentially clinically meaningful effect.

Interestingly, the study investigated a allogenic stem cell product, meaning one derived for a dog other than the intended patient. Most current stem cell products used in companion animals involve taking fat or blood form a patient, processing it in various ways, and then using that product in the same patient (called autologous stem cell therapy). While this has some advantages in terms of minimizing the risk of infections and adverse reactions to foreign material, it requires these patients to undergo anesthesia and surgery to collect the sample, which has its own risks and costs, and it yields inconsistent material for treatment. An off-the-shelf stem cell product derived from a single patient and then processed and maintained by the manufacturer can be better standardized and assessed for quality, it can be a more predictable therapy, and it can avoid additional anesthetic and surgical procedures for patients, so there are some advantages to this approach.

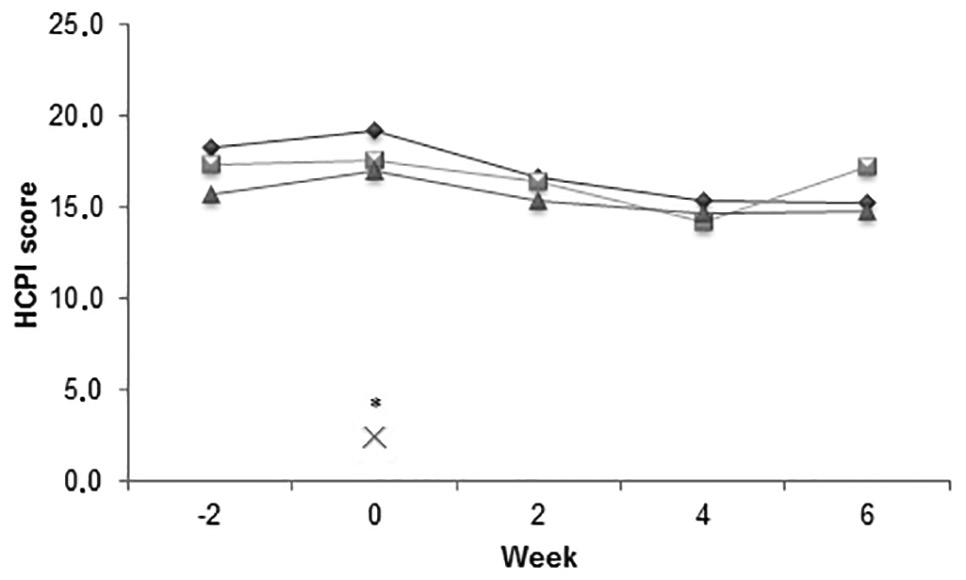

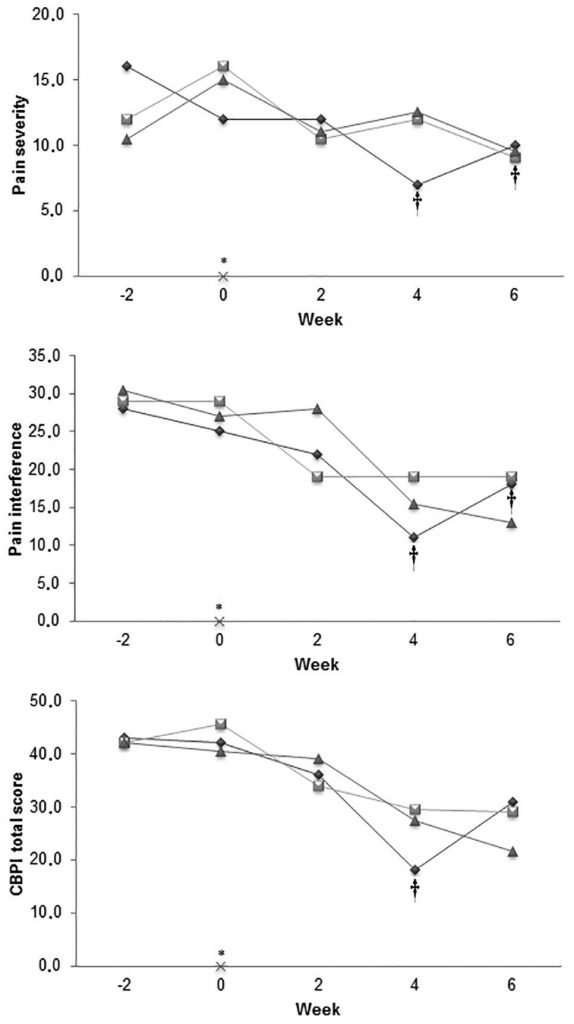

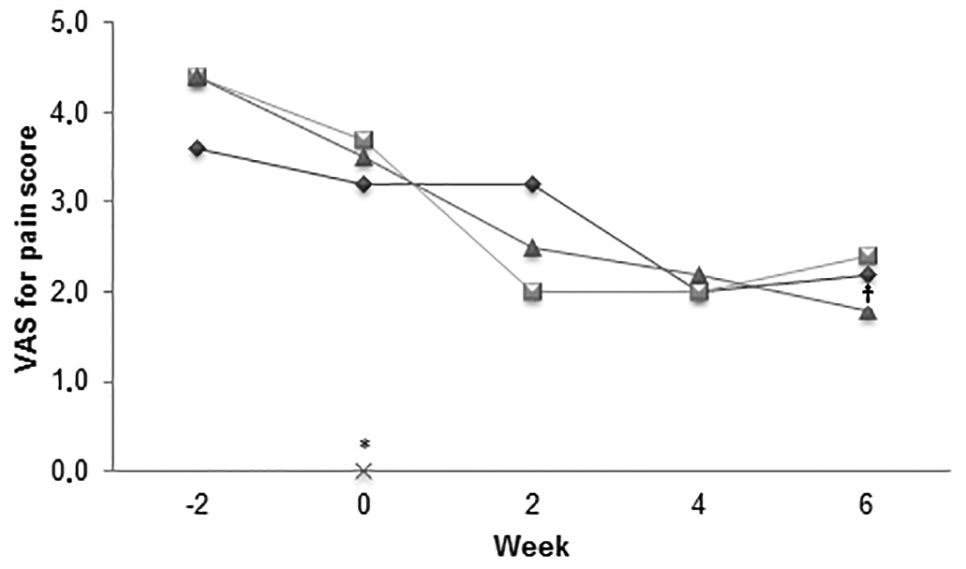

The study randomized 93 dogs with arthritis in one or more joints to treatment with the stem cell product or a placebo injected into the affected joints. 74 of the subjects were included in the final analysis, with the rest being excluded for failing to adhere to the study procedures or other reasons. The primary outcome was the owner assessment 60 days after treatment of three specific activities chosen by the owner at the beginning as important measures of comfort and function. The secondary outcomes were assessments by the veterinarians treating the patient and overall assessments by both owner and vet. These are inherently subjective outcome measures, which are somewhat less reliable than more objective measures, such as force-plate analysis. However, the mechanisms for minimizing bias were good enough to make these reasonable choices despite the potential for caregiver placebo effects.

The primary outcome showed both a statistically significant and a clinically meaningful difference of about 24% in degree of improvement between placebo and treatment groups. In other words, the placebo group owners reported a 55% improvement, which shows how strong a placebo effect by proxy can occur. However, the treatment group owners showed a 79% improvement, which is enough of a difference to suggest some real change.

The veterinarian assessments also showed large and significantly greater improvements in the treatment group compared to the placebo group. The overall owner assessment was the only measure to show a difference too small to be statistically significant. However, the size of the effect and the consistency of the effect across different measures are arguably more important.

So overall, the study strongly suggests this particular stem cell treatment had some real beneficial effects, and no significant undesirable effects were noted, though with stem cells many of the problems they might cause would not necessarily be expected to appear only 60 days after treatment. This does not, of course, validate all of the myriad of stem cell therapies and uses of these out there. In particular, it doesn’t necessarily tell us that the autologous stem cell products which are most widely used have similar benefits.

Naturally, no single study is ever sufficient alone to prove safety and efficacy. The FDA approval will likely involve further research which hopefully will support these findings. If so, this would be an important step towards producing a reliable and consistently effective stem cell treatment for arthritis in dogs. I have always been cautiously hopeful about this approach, and I am pleased to see the very beginnings of the kind of research evidence needed to make stem cell treatments a reasonably evidence-based procedure.

Bottom Line

Overall, the evidence supporting stem cell therapies in companion animals is very weak and preliminary. More research is absolutely appropriate, but clinical use is still an uncontrolled experiment on our patients and should only be done with clear and detailed discussion with owners about the uncertain risks and benefits and after all treatments with better supporting evidence have been considered.

The best evidence so far, a clinical trial involving treatment of dogs with arthritis, does suggest that allogenic stem cells injected into arthritic joints may improve comfort and function enough to be worthwhile, with no apparent short-term side-effects. Even for this process, however, more research is needed to justify widespread use. Hopefully, this will emerge in the course of pursuing FDA approval for this method.