A key focus of this blog is to promote a science-based perspective for veterinary medicine. I believe that relying more on science and less on habit, tradition, intuition, and personal experience will lead to better care for our patients. While almost everyone claims to support science when asked, it is clear from the topics I report on that many in the veterinary profession, particularly those practicing alternative medicine, don’t really mean it, or at least don’t understand what science-based medicine really means. It is simply impossible to believe in the scientific approach and still practice homeopathy without the most egregious kind of doublethink.

The best hope for improving veterinary medicine and moving further towards science and further away from mysticism and pseudoscience is to teach veterinary students how to think and reason critically, how to evaluate the quality and meaning of different kinds of evidence, and how to recognize and watch out for the errors and biases in their own observation and reasoning; in other words, to teach the epistemology of science and evidence-based medicine.

The alternative, of course, is to teach continuing reliance on blind acceptance of the dogma of one’s teachers and uncritical faith in one’s own observations and the anecdotes of others; in other words, to teach the epistemology of alternative medicine. I have written about the philosophical differences between science and alternative medicine before, and the two often have very different, and incompatible, ways of establishing and verifying knowledge.

Unfortunately, what veterinary students are taught is not determined by any objective standard of reasoning about science and the nature of how knowledge is obtained and evaluated, but by what the teachers believe about the content and processes of veterinary research and practice. And teachers, like all other human beings, have their own biases and interests. There are also complex politics in academia, as in any other human endeavor. And, of course, few of the teachers in veterinary medicine today have themselves been trained in modern evidence-based medicine, which has only become the dominant approach in the human medical profession over the last two or three decades. The practice of passing along the “wisdom of the ages” to the next generation of doctors is far older and more entrenched, however less reliable an approach it may be.

So despite the fact that alternative therapies are currently a relatively marginal part of veterinary medicine, they appear to be growing some in popularity and respectability, and this raises the danger that the next generation of veterinarians will be trained with the idea that even egregious quackery like homeopathy and energy healing are potentially useful practices to be taken seriously. What, then, are the veterinary students of today being taught? How prominent are courses in evidence-based medicine and in alternative medicine?

A thorough answer would require a detailed review of the curricula of all the veterinary schools in the U.S., or any other area one was interested in. I certainly do not have the resources to conduct such a study. However, there is some information available which suggests the relative emphasis on the fields of evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) and complementary and alternative veterinary medicine (CAVM).

The Teaching of EBVM

The Evidence-Based Veterinary Medicine Association (EBVMA) has informally surveyed the veterinary schools in the U.S. and identified which have courses in EBVM and which teach at least some of the methods or concepts of EBVM in other courses. This information is available on the EBVMA web site.

As far as could be determined, of the 35 schools looked at, only one has a course specifically in EBVM, and one other has a course that covers the basics of EBVM along with other material aimed at raising the standard of practice. Beyond that, most schools (26) include some EBVM material in other courses, such as those in public health, epidemiology, and statistics. This suggests that most veterinary students get some exposure to EBVM, but rarely is it presented comprehensively or as an essential strategy for high quality clinical practice.

This is consistent with the findings of a pilot survey, also conducted by the EBVMA in 2011, which suggested most private practitioners have heard some EBVM terms but have little understanding of them and feel unprepared to find and appraise research studies. In this survey, 85% of respondents reported no formal training in literature search and appraisal, and between 30% and 85% were not sufficiently familiar with key EBVM concepts to explain them to others.

It is also consistent with the results of a study carried out in Belgium, in which the decision-making practices of veterinarians were investigated. In that study, “The EBM approach was never mentioned in any of the interviews, with occasional isolated opinions such as ‘The information from research is not important and does not influence decisions.’”

For practicing veterinarians, there is little opportunity to remedy this deficiency in education once they leave school, as there are few courses in EBVM available privately. Some EBVM material is covered in continuing education meetings, and there is a project beginning at one veterinary school to develop EBVM curricula for vets in practice, but the options are limited.

The Teaching of CAVM

A survey of CAVM courses at veterinary schools was conducted in 2011, and it found a somewhat different picture for this collection of therapies.

Sixteen schools indicated that they offered a CAVM course. Nutritional therapy, acupuncture, and rehabilitation or physical therapy were topics most commonly included in the curriculum. One school required a course in CAVM; all other courses were elective… Eighteen veterinary medical schools had no course offerings in CAVM…

4 [schools] had positions (< 0.5 full-time equivalent faculty) devoted to teaching CAVM…

This suggests that CAVM is being taught pretty widely in veterinary schools; perhaps more widely than EBVM. However, CAVM is a heterogenous category notoriously difficult to define. It is common for CAVM proponents to label perfectly ordinary conventional subjects, such as nutrition, as alternative. The inclusion of nutrition in this survey raises questions about whether the therapies being taught were truly alternative (such as raw diets, TCM-guided nutrition, etc.), or simply an appropriation of science-based nutritional recommendations to the standard of “alternative” therapies.

Similarly, physical therapy and rehabilitation are, in human medicine, perfectly ordinary conventional medicine. Due to the limited research in this area in companion animal medicine, this filed is a bit of a gray area at the moment, with reasonable extrapolations from human medicine employed side-by-side with alternative therapies like Veterinary Orthopedic Manipulation, chiropractic, and acupuncture.

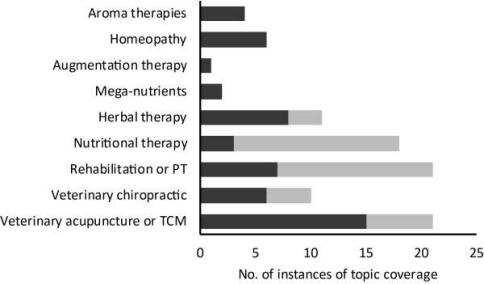

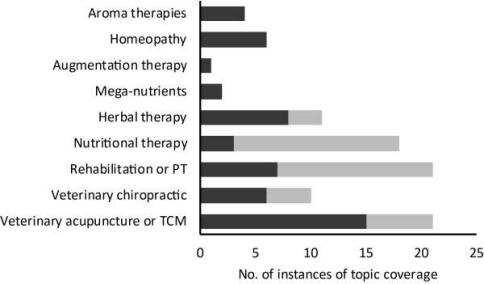

This figure illustrates the sort of CAVM modalities being taught, and it certainly includes both outright quackery, such as homeopathy, and more ambiguous practices.

Figure 1—Coverage of topics in a CAVM course (dark gray bars) or in other courses in the curriculum (light gray bars) at 16 COE-accredited veterinary medical schools that offered a course in CAVM. PT = Physical therapy. TCM = Traditional Chinese medicine.

The survey also suggested that CAVM was more widely taught in 2011 than it had been in a previous survey.

Coverage of CAVM appears to have increased substantially since a previous survey3 of CAVM coverage in veterinary medical curricula. In that survey,3 7 of 23 veterinary medical schools offered courses in CAVM, compared with 16 of 34 schools that offered courses in CAVM in the present survey

It would not surprise me if there has been some growth in the teaching of CAVM as my impression is that there is some growth in the popularity of these therapies in veterinary medicine, though that is difficult to determine objectively. However, the key point regarding the teaching of these methods is made by the authors in this statement:

…the extent of CAVM coverage appears to be driven largely by individual faculty members who happen to have an interest in 1 or more areas of CAVM.

There is no tsunami of new evidence to support greater integration of CAVM in the veterinary curriculum; there are simply individual faculty members interested in such methods. This illustrates the potentially significant impact individual faculty members can have on the profession.

The other key point identified was that the leadership of the veterinary schools appear to have some concerns about the evidentiary integrity of CAVM:

The most frequently and strongly expressed comment in the survey reported here was that any coverage of CAVM in the curriculum, whether in a separate course or as part of other courses, must be via evidence based medicine.

This sounds encouraging, and it indicates that the folks surveyed realize CAVM has a shaky evidence base. However it is unfortunately too easy for proponents of even egregious nonsense like homeopathy to generate the appearance of scientific evidence or rigor. Simple li-service to EBVM or the generation of numerous low-quality studies doesn’t prevent the integration of pseudoscience with CAVM therapies that have real potential benefits.

I have no doubt that the leadership of most veterinary colleges are sincere in their desire that their students be taught truly science-based medicine, I know that the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association (AHVMA) and other pro-CAVM groups are eager to use research, and funding for research, as a pre-text for promoting therapies that are truly incompatible with legitimate science. The charitable foundation of the AHVMA has made the following statement:

One of our goals is to generate five to seven academic and research teaching hospitals in the United States of America that are qualified, able and willing to do appropriate evidence-based veterinary research into these techniques and philosophies…our ten day campaign that netted over $480,000 in contributions dedicated to this purpose.. Our goal is to generate a twenty million dollar fund to support these centers.

Does anyone believe these individuals or groups will find any CAVM practices to be without merit? Is there any research that can convince the leadership of the Academy of Veterinary Homeopathy that homeopathy is without value? I am not highly confident that the substitution of marketing for real science will be readily seen for what it truly is.

It must also be noted that, in contrast to the situation with EBVM, there are numerous for-profit organizations willing to train and “accredit” veterinarians in the practice of specific CAVM practices. The marketability of alternative therapies is inherently greater than that of the EBVM method, and this makes the financial resources available for promoting and teaching CAVM, and the incentives for doing so, correspondingly greater.

Bottom Line

There is some teaching of the principles and methods of EBVM in veterinary schools, but it is less consistent and integral to the curriculum than it should be, and it is not likely to produce veterinarians committed to EBVM and capable of practicing according to EBVM standards. In contrast, there are much more aggressive and well-financed efforts under way to promote training veterinary students in CAVM methods, both those with some plausibility and reasonable supporting scientific evidence and those that are clearly nonsense. It seems likely that this situation will lead to the greater appearance of legitimacy to CAVM in general, regardless of the actual development of compelling scientific evidence favoring CAVM practices. Students taught CAVM will become vets who practice or refer for CAVM simply because it was presented to them as appropriate in school. Students not taught EBVM will not likely investigate and critically evaluate the evidence base for these practices for themselves but will take the word of their teachers for the value of such therapies. This has the potential to lead to more widespread use of ineffective therapies and less critical thinking among veterinarians, which will not improve the care veterinary patients receive.

It is incumbent, then, upon anyone committed to a sound scientific basis for veterinary medicine that we encourage the teaching of EBVM principles and methods and insist upon the application of these uniformly, to both conventional and alternative practices. No special exemption from scientific standards of evidence should be granted to alternative therapies simply because they have a history of use or dedicated adherents. Truly fair, unbiased, and scientific evaluation of all therapies can only take place if the epistemology of science is accepted as superior to the fuzzy epistemology of history, tradition, and personal experience, and if EBVM methods are consistently, rigorously, and uniformly applied. And this will only happen in the future if veterinary students are trained to think the way now.

Peter Aldhous

Peter Aldhous